Did Blair deliver, deliver, deliver?

Kate White timed it right, according to her colleagues. At the comprehensive school where she studied, teachers tried to tell her that she could do better than go into teaching. “All the way as a teenager, I had staff trying to put me off,” she says.

But by the time she completed her training, after she had finally realised that teaching was her vocation, the education system was on the brink of a historic change.

It was 1997. Many teachers had long felt bruised and demoralised from a lack of funding and political neglect. In the run-up to the general election of that year, Labour had promised to force a change, and on the night of 1 May it became clear that it would have the opportunity to deliver it: Tony Blair’s party won by a landslide.

Over the next 10 years, there were changes that transformed schools, but the outcomes were profoundly ambiguous.

There were changes that were seized upon by political opponents and turned to purposes that still divide the Labour Party. There were changes that were abandoned for fear of negative press and public reaction. There were changes that will undeniably endure: billions in capital spending rebuilt thousands of schools, for example.

“There was a real sense of something happening,” recalls White.

But ask her if the school system has really improved since then, and there’s a surprisingly long pause. It’s a common reaction: the impact of the Blair era divides teachers, school leaders and parents.

So after all that optimism, do the key players in education believe that they delivered on Blair’s promise of transformation?

And what has been the enduring legacy of those frantic 10 years of reform - from 1997 to 2007 - for the hundreds of thousands of people who work in our schools?

Few education secretaries have come into power with as clear an idea of what they were going to do as David Blunkett (now Lord Blunkett). He had been in post as shadow education secretary since the autumn of 1994; all that preparation meant that he could publish a White Paper within 63 days.

Now he argues that any doubts about the impact of Labour on education are the product of poor memories. In 1997, the school buildings were evidence of the low priority that had been placed on state education, he says. “Windows were falling in, it was an absolute scandal.”

In the 1990s, the Audit Commission described the state of buildings as being at “crisis level” in some schools and warned of a “maintenance time bomb”, as funds for repairs had to be diverted to maintain teaching resources.

In response, Labour aimed to create buildings that were not just adequate, but inspirational. Capital funding rose from just £600 million in 1996 to £7.4 billion by 2009.

“That school building programme will turn out to be the biggest investment in school buildings in this country certainly since the Second World War and possibly in the whole history of state education,” says Sir Michael Barber, Blunkett’s chief adviser for school standards and later head of Blair’s No 10 delivery unit.

“In 2030 and 2040 people will still be talking about those buildings.”

It’s true that many schools were transformed with iconic designs, but a few were left with expensive white elephants. And many were left untouched: according to a damning report, Better Spaces for Learning, published in May last year by the Royal Institute of British Architects, too many school buildings are still dangerous, dilapidated and poorly built.

And one reason why people might still be discussing school buildings in 2030 is that only then will schools finally have made the last of the 25-year private finance initiative (PFI) repayments. For many heads, these payments are an increasingly burdensome legacy of Labour’s building boom.

The service [by the PFI provider] is slow, poor and lacks competition,” says one secondary head, who warns that, despite her school having an impressive building, the costs negatively impact on her ability to provide the best education for her students, particularly when budgets are so tight. “My PFI provider wants nearly £1,000 to put up 60 coat pegs,” she adds.

When they first came into power, of course, Blunkett and Barber were not focused on atriums and new classrooms, but on what happened inside.

Their first move was to implement the “national strategies” with the daily literacy hour and maths lesson: a highly prescriptive, “voluntary” framework designed to raise standards. Everything else that took place in schools would rest on that foundation.

Then, over more than a decade, Labour flooded the system with funding to support this drive for higher student attainment.

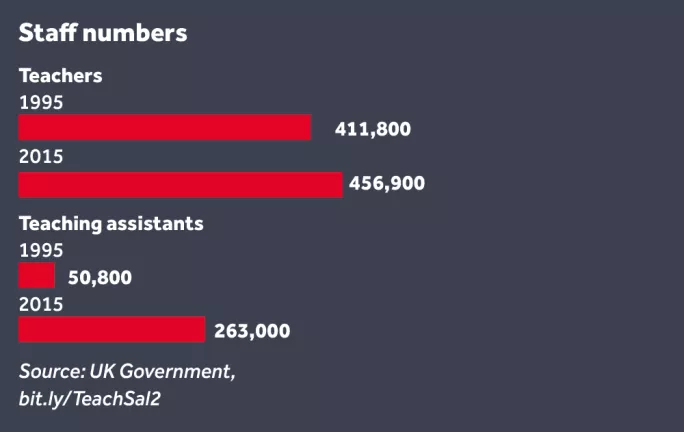

White recalls genuine excitement in the profession over the rising numbers of TAs and the introduction of time for planning, preparation and assessment.

“That was something the government did that really made us feel valued,” she says.

But like thousands of fellow teachers, she hated the literacy hour.

“It killed creativity,” she says. With her degree in English, she felt patronised and constrained, although she was grateful for the guidance in numeracy. “For me, it took the mystery out of maths,” she adds.

No one should have been surprised that teachers were being dictated to: Blair had promised “continual assessment, targets set, instant action where they are not met”. It was very much a carrot and stick policy of more money, but more scrutiny, too.

“We were trying to create a kind of movement. We knew that literacy standards hadn’t risen for about 50 years,” says Barber.

‘Patchy and inadequate evidence’

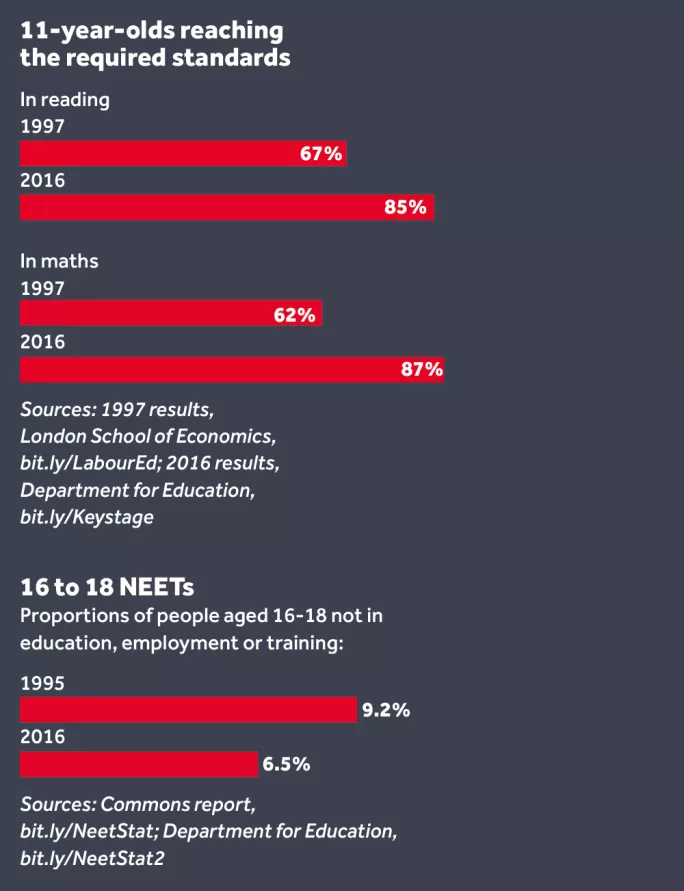

For Blunkett and Barber, the evidence shows that the policy worked. They point to the Trends in International Maths and Science Study (Timms ) results last year, which showed that England was the most improved system in the world for maths at primary level. “That is not an accident. That is because we chose to do the numeracy strategy,” Barber says.

But it’s an irony that the measurement-obsessed system introduced by Labour cannot produce a consensus about how much the system improved - or even whether it did.

Rob Coe, professor of education at Durham University and director of the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring, points out that the Timms maths result at age 10 was the only international survey that showed improvement. By age 14, these gains seemed to disappear.

Meanwhile, the government’s own measures, from key stage tests to GCSEs, were dogged by claims that grades were inflated to meet the targets.

Because of these doubts, evidence for systematic improvements in school standards since 1995 is “patchy and inadequate”, Professor Coe says.

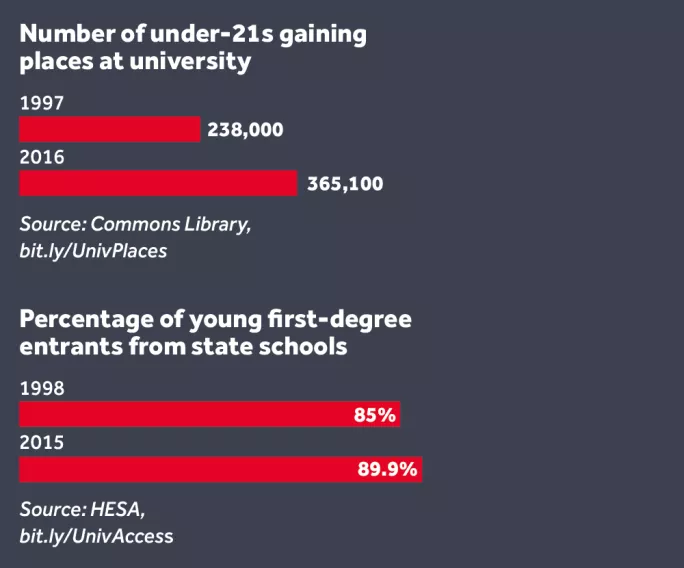

Blunkett and Barber point to other ways in which the school system has transformed life chances: university entrances from the most deprived areas were at their highest level ever in 2015 - a cohort that began their primary education at the start of Blair’s second term.

Some major achievement gaps have been closed, too.

“Although in England and in the British media we are quite grudging about what we’ve achieved, other countries look at what we’ve done and they think it’s amazing,” says Barber.

“They look at the fact that Bangladeshi students [in England] now exceed the national average and they think, ‘How have you done that?’ They look at the fact that Pakistani students have narrowed the gap and they think, ‘How have you done that?’ They can’t do it with Latino and African-American students in America - ‘How did you do it here?’”

Blairites in education believe they took a real risk with their ambitious targets. At the first cabinet meeting after the 1997 election, Barber has described being asked by Blair if he was sure about the 80 per cent target for literacy by 2002.

“Everyone went silent and looked at me. If there was a single moment when I realised the extent of my personal accountability, that was it,” he recalled in his book, Instruction to Deliver. Blunkett told him: “If I go down, you’re going down with me.”

In fact, it wasn’t Blunkett and Barber who faced the consequences when Labour missed the target. Instead, Estelle Morris, now Baroness Morris of Yardley, resigned just a year after she had replaced Blunkett as education secretary.

If anything summed up the power of the accountability system Labour had created, it was the fact that an education secretary could fall victim to it.

That legacy of punitive accountability lives on, stronger than ever. Just last month, Tes ran a feature about the fear factor in education, which many see as a direct result of unreasonable accountability.

“As heads, we are the buck-stoppers and there’s an increasing sense in the current high-stakes accountability climate of, ‘You’re only as good as your last GCSE results or inspection,’” explained Helena Marsh, executive principal at Linton Village College in Cambridgeshire. “In three years, at least three heads in my area have, following a negative inspection or poor results, vanished. That tends to have been the governing body’s decision if they feel that the head hasn’t served the school well. That fuels fear. We need a wholesale review of school accountability to provide a more humane and intelligent way of judging schools, looking at peer review and other vehicles for self-evaluation.”

Morris believes that accountability has got out of control: after funding, she says, reforming accountability is “the biggest challenge in the system”.

“Imagine there was a drug for the common cold and 40 per cent of people got cured,” she says. “Then you come up with something, an intervention, and it rises to 70 per cent - you’d call it a success. In education, we call it a failure.”

She suggests that education needs better ways of coping with failure, that not every missed target requires an intervention (some situations will improve without an intervention) and that we are too quick to mistake a change in leadership for a solution.

Her own resignation shows that the increase in accountability was not just a result of Labour’s refusal to tolerate failure, however. It was also a result of the new political significance that Blair had given to education.

“If you made me choose one single thing that Blair achieved, it was the change in the nation’s and government’s approach to education,” Morris says. “He really propelled it up the Whitehall agenda and up the government’s agenda.”

It was attention that the education system had been crying out for. But in making education a political priority, he also increased its value for political attacks. And that is one legacy that is not going away. When a coalition government came into power in 2010, many expected the Labour education legacy to be dismantled. Instead, education secretary Michael Gove pushed many Blairite policies, such as academies, further and faster, proclaiming himself the “heir to Blair”.

But for Labour figures like Charles Clarke, education secretary from 2002 to 2004, this was just a political smokescreen aimed at dividing the left. For him, the legacy was already under threat.

“They completely lost the key social argument of the academy programme, which was as a booster programme for areas of historic underperformance. They kind of purloined the word and made it into a general thing for breaking down the local authority influence in education,” he says.

It’s an argument that Morris takes up. As chair of the Birmingham Education Partnership, she sees first-hand how the oversight in schools has been fragmented by academisation. With academy heads, regional schools commissioners, the local authority and the partnership itself all around the table, “on bad days, it can be nightmarish,” she says.

“We’ve chased something called independence and autonomy, and what are we doing now? Having broken the school system down into 24,000 autonomous schools, we’re rebuilding them into multi-academy trusts. It’s the biggest sign we’ve got it wrong.”

For Blunkett, the dismantling of Sure Start - a scheme to provide help to infants from poor backgrounds before they started at school - was the first break with the Blair legacy. “I think it’s actually criminal the way from 2010 this was allowed to erode,” he says.

The legacy also suffered self-inflicted wounds. Critics say that Labour failed to address the curriculum: its root-and-branch attempt was abandoned after Sir Mike Tomlinson, leading the review, had recommended replacing A levels and GCSEs with a new diploma.

“I think that was the big mistake,” says Clarke. “It was fear of the general election and the various issues around, in quotes, ‘abolishing A levels’. A ridiculous argument, actually. I think if I’d stayed as education secretary I’d have been able to carry it through.”

Labour’s accountability system also left it open to attack. Gove had seized on arguments about the gaming of league tables through “soft” qualifications to inflate results, and when in power he set about reshaping the curriculum.

But even as he infuriated the Labour benches, Gove absorbed many of Blair’s assumptions, including the idea that grammar schools were not the solution to school improvement. With Theresa May’s accession to power, this consensus (“No return to the 11-plus!”) faced a direct challenge, as the creation of new grammars moved to the centre of education policy.

William Davies, a political economist at Goldsmiths, University of London, sees this as a defining shift - a rejection of the laissez-faire, competitive system that united Blair and Gove. Instead, he says, May seems to favour a model of the state as protector of the good against the bad, sorting wheat from chaff, whether they are skilled migrants or talented, underprivileged students.

Blunkett dismisses the grammar school revival as “neolithic” - “constantly looking over our shoulders to some bygone era that people remember with nostalgia and forget that it didn’t work for the majority”.

Instead, he calls for the government to promote “grammar school streams” within schools, which could reinvent the Gifted and Talented programme - so cherished in the Blair years - without separating children into different social strata.

Not everyone believes that new grammar schools would be a nail in the coffin of Blair’s vision for education, however. As the incoming head of education and social reform at Policy Exchange, the most influential right-wing thinktank, John Blake is a rare figure in education who endorses the policy. As a former teacher and NUT activist, his career has mirrored the country’s political arc from Blair to May.

He argues that the grammar school policy won’t mean an 11-plus for everyone, but instead it will be one tool among many for trying to raise achievement in areas that resisted improvement in the Labour years - a way to finish the job that Labour started.

“Particularly in the light of the Brexit referendum result, you can’t keep going around the country to places far distant from the metropolis and saying, ‘Well, there are loads of good schools in Hackney,’” he says.

It’s a tribute to the divisive power of the Blair years that his education legacy remains so contested. But by one measure, his influence has collapsed: in January, an Ipsos MORI poll found that just 1 per cent of the public believe education is the most important issue facing the nation. The proportion has steadily declined since a peak in 1997.

“Lord above!” says Blunkett when told about that result. “Education, education, education - we couldn’t have said it more clearly!”

Even this is ambiguous, however. Do the public care less because they’re less interested in education, or do they believe that schools have improved so much that they do not need to be concerned?

With schools facing funding cuts of 6.5 per cent in real terms by 2019, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, teachers must hope that the former level of public concern returns soon.

Under Blair, political prioritisation, stiff accountability and generous funding went hand-in-hand. Since that link was broken, teachers have found out that although the carrots run out, the stick lasts forever.

“Morale was possibly at its highest then; it’s not like that now,” says White.

But what has remained the same, however - and it is a major achievement of the Blair years - is the raised expectation for all children to achieve, according to Morris.

“Now it’s impossible to find even the most right-wing politician who makes an argument for having aspirations that are lower than high standards for every child,” she says.

Blake adds that another remaining part of Blair’s legacy that should be inarguable is that the profession is more empowered politically.

He believes that teachers are now in a better position than ever to shape the policy debate themselves. Blunkett’s Department for Education and Employment overrode civil service objections to bring in headteachers and teachers to work on policy. Moves such as this contributed to the cult of the superhead, several of whom fell from grace. But along with a new focus on recruitment and teacher development, it also paved the way for the discussions about policy and pedagogy that take place every day in staffrooms, across the internet and in conferences.

“This isn’t a conversation being had between wonks in Whitehall, it’s a live issue that takes in teachers and headteachers up and down the land,” says Blake.

When White eventually answers the question of whether the education system has improved in her 20 years, though, she does so tentatively.

“Yes? I hope so. I feel that we are a lot more rigorous.”

All things being considered, perhaps the Blair years did not quite manage a “new dawn”, then, but rather instilled a “new hope” in education: a new hope that still remains today, and that was not there when White was at school, that things can and will only get better - for everyone.

Joseph Lee is a freelance journalist. He tweets @josephlee

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters