I vividly remember the panic when, upon starting a course as a postgraduate student, I noticed the stipulation that all tests and exams had to be done on a computer.

What? I’d only ever written exams by hand and was worried that, with my rudimentary IT skills, I’d spend more time faffing about trying to get things the computer to work than actually answering the questions.

Now, not even 20 years after starting that course, I’d hate to be forced to write any more than a few words by hand. My handwriting, once fluid and elegant, has collapsed into an ugly scrawl. Sometimes, I come home from the supermarket without an essential ingredient for dinner because that word was impossible to interpret on my shopping list.

Times change, and we have to move with them - don’t we?

Janet Brown certainly thought so. In an interview I did with the former chief executive of the Scottish Qualifications Authority in December 2017, she suggested that handwritten exams could disappear within a few years, and that it would be “very unusual” if they were still around 10 years later, in 2027. Electronic assessment was already used for some courses, she said, and “society’s going that way”.

This may seem like common sense: isn’t forcing students to write by hand - as many thousands, in the midst of prelims season, are doing - an archaic practice, when it’s something they’ll barely ever do in life?

And isn’t it also patently unfair? You hear concerns about markers’ bias against exam candidates with poor handwriting; although there has been research suggesting that such fears are overblown. Taking handwriting out of the equation altogether would, you’d think, create a level playing field.

And what about the many thousands of teachers and others who make the exams system function? They’d spend fewer frustrating hours trying to decipher teenage hieroglyphics in the pursuit of giving everyone a fair mark, while the administrative burden of having to scan handwritten scripts would disappear.

We should be wary, however, of what you might call a tyranny of the present: a tendency to vaunt current ways of doing things and disparage the ways of the past.

It was this sort of thinking that resulted in architectural treasures in Scotland’s great cities being blithely flattened in the decades after the Second World War.

Yet, it all seemed very sensible at the time: in Glasgow, the 1945 Bruce Report even proposed knocking down Central Station, the Kelvingrove and the Charles Rennie Mackintosh-designed School of Art, now considered three of the city’s greatest buildings.

Austere, draughty old structures were seen as holding back progress, whereas modern, brutalist design offered a glittering future. Now, it’s standard to shake your head in dismay at the thought of what was lost - and almost lost - in that postwar building frenzy.

So we should at least consider that, while handwriting may seem an anachronistic skill just now, we may not fully appreciate what it offers until it has been definitively consigned to the past.

In an October 2018 article for Tes, Daisy Christodoulou, director of education at the assessment organisation No More Marking, looked at recent evidence on the pros and cons of handwriting. Research suggested, for example, that handwriting could help children who were learning to read and write, because the act of writing a letter helps to build the mental representation of writing in ways that typing does not do.

For those in secondary schools, colleges and universities, it appeared that taking notes by hand forced them to think more about the content of classes and lectures.

It is absolutely right that in our fast-changing and increasingly digital society we scrutinise the merits of an old way of communicating - but let’s not dismiss it out of hand.

@Henry_Hepburn

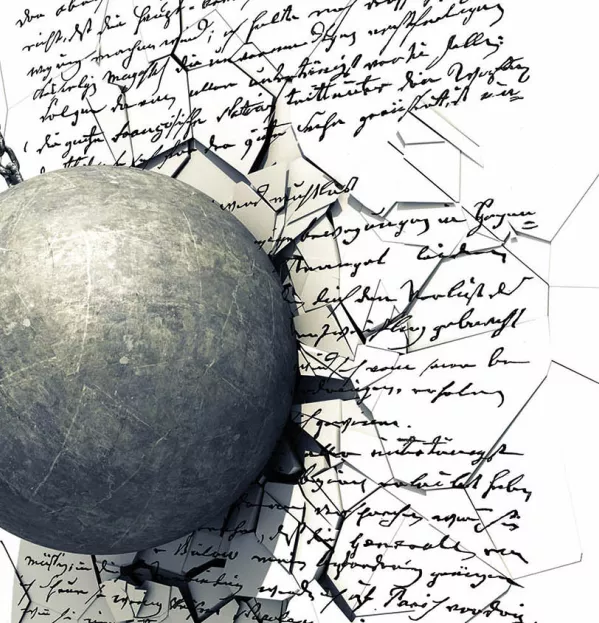

This article originally appeared in the 17 January 2020 issue under the headline “Don’t take a wrecking ball to the grand old edifice of handwriting”