To find the right solution, ask the right question

As mentioned in the “getting started” article above, every teacher and school leader is time-poor and resource-poor.

It is no surprise, then, that we are prone to making quick decisions, often based on scant evidence.

Savvy businesses prey on our vulnerabilities by gilding their products with dazzling quotes and attractive evidence. Or we can fall prey to seeing a bit of research we like the look of and then retrofitting it to our classroom need.

And yet, we know that classroom challenges have no quick and easy fixes. So how should we be using research to improve our teaching?

To better understand the vast majority of the issues that teachers face in the classroom, we need to better understand the barriers to learning that are too often hidden in plain sight.

To do so, teachers and schools need to develop a good “mental model” of learning. That is to say, how do all the complex moving parts that influence learning interact? From memory to motivation, from metacognition to reading.

Then when we come across a problem, we need to plot out our hunt for a solution by asking a good inquiry question.

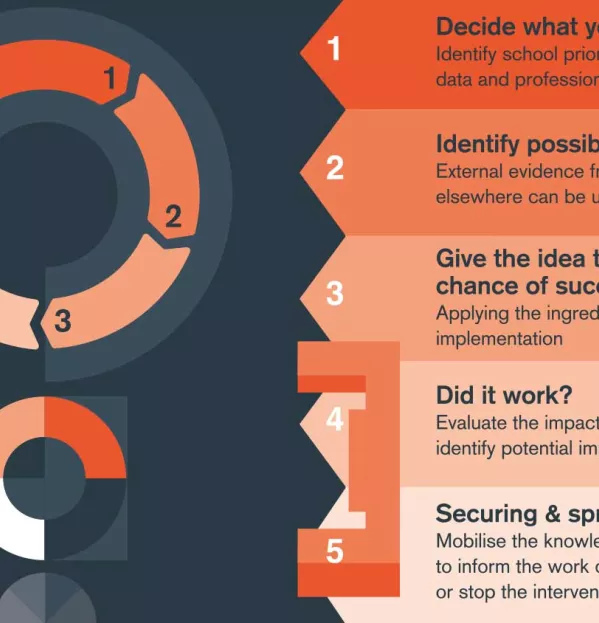

Asking the right question will mean that we can better discipline our professional practice. A useful tool to help teachers (and school leaders) is the Education Endowment Foundation “School Improvement Cycle”. Essentially, it offers a framework to tackle school problems, big and small:

1. Decide what you want to achieve

Let’s use the example of a student called Jimmy. He had arrived in my GCSE class as a naughty, uninterested teen. But I soon discovered this was down not to his hormones but a lack of fluency when reading that he had managed to mask until that point. So the challenges were: what did I know about “reading fluency”? How is it a barrier to understanding reading texts? How would this affect Jimmy’s effort and motivation?

2. Identify possible solutions

So then, of course, it was a case of, “What can I do to help Jimmy?” I surveyed the research for different daily approaches I could use. I eventually decided that some supported one-to-one reading would do the trick, so I came up with the following enquiry question to consider my approach to helping Jimmy: “How will one-to-one reading [intervention] for 10 minutes in form time, three times a week [duration], improve Jimmy’s reading fluency [outcome]?”

3. Give the idea the best chance of success

Now, exactly how I got Jimmy reading matters. With no teaching assistant to work with Jimmy, nor my group, I had to engineer some time with him in form period. For every school problem, implementing the “answer” in our unique context is critical. Even the best “answers” fail without the time, training and resources.

4. Did it work?

The often-ignored tricky step of evaluating the “answer” came next. More research brought me to a great Tes article on assessing reading fluency by Megan Dixon (see bit.ly/FluencyRead). The useable assessment tool of the “Multi-dimensional Fluency Scale” was vital.

5. Securing and spreading change

So how do we support Jimmy across the school? Of course, every teacher needs to better understand reading fluency - for Jimmy, as well as other pupils. So we can then ask, “Which other pupils have Jimmy’s problem?” or, “What other barriers to learning are present for pupils in my classroom?”

Schools and teachers tackle school improvement and issues for individuals like Jimmy every day, but our efforts are often squeezed by limited time and resources. There are no quick fixes, but with more focus on being informed by a deep mental model of learning, followed by a disciplined approach that harnesses the best available evidence, we can better tackle our problems.

Alex Quigley is an English teacher and the director of Huntington Research School in York. He is the author of Closing the Vocabulary Gap, published by Routledge

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles