Governance review is a chance to put pupils first

The governance review of Scottish education signalled recently by education secretary John Swinney should not have surprised many people - the surprise is that it has taken until now to happen. But why is this review deemed necessary, less than a year after the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) gave the Scottish system a clean bill of health? And will it lead us to the sorts of improvements desired?

On the face of it, it’s remarkable how well 32 councils have managed to deliver education given their imbalance of size and make-up (a consequence of the Conservative review of local government in Scotland in the early 1990s). Education is the only major service of national complexity left in local authority control and it’s apparent that cracks in the relationship with Scottish government have been appearing for years. John Swinney is not the first education minister to appear frustrated by the often fractious relationship government has with local authorities.

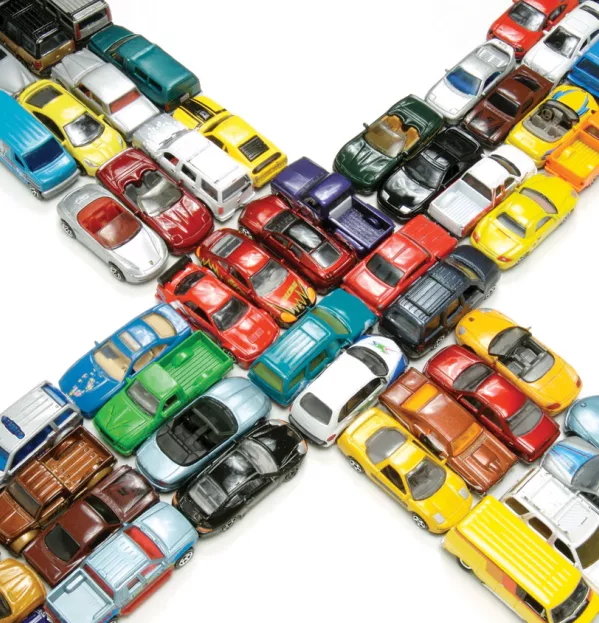

A car crash was bound to happen: Scotland’s government and Parliament both have high ambitions for education but little direct control, while their council colleagues have decision-making responsibility for most of the £5 billion education spend. And the removal of ring-fenced funding for education nearly a decade ago started the steady erosion of local education budgets.

Public sector financial settlements have been difficult of late, and the stand-off between the two sides over teacher numbers brought matters to a head. The recently published financial review of early-years services points to £140 million being unaccounted for across the 32 councils, which, no doubt, will add to the financial tensions. Local authorities and the umbrella body representing most of them, Cosla, have not always boxed clever in this power battle, with local and national priorities appearing to be in sharp contrast.

Shared services agenda

The inability or unwillingness of local authorities to demonstrate a shared services agenda in a small nation such as ours is problematic.

The failure, after two attempts, to create amalgamated education authorities across four small council areas signals that national intervention is required. We are a small country with big ambitions in education and, simply put, we can’t justify 32 education authorities with the variations in size, scale and capacity that exist.

The governance review should not, however, be solely about pitting councils’ priorities against those of national government. If such a review is to succeed, we require all matters to be under the microscope. National bodies involved in education should also be part of the review, and the role of Education Scotland, in particular, in any new model must change. The key question must be this: what added value is that organisation bringing to schools?

A statutory inspection role should be in the frame for retention; other aspects of Education Scotland are questionable. Is it time to establish a new “middle tier” in Scottish education to support and challenge for schools? Any such tier should include council quality improvement teams, national agencies, university teacher education, third-sector organisations and non-teachers who can work with schools. And it must reach out across Scotland.

The commitment by Mr Swinney to devolve extra funds to headteachers has had mixed responses, even from headteachers’ representative bodies. With increased responsibility, especially around finance, comes increased accountability. The recent report on the recruitment of headteachers (“Fears over standards as staff shun headships”, TESS, 16 September) outlined one of headteachers’ biggest frustrations: their inability to concentrate on their core purpose of leading learning.

With support staff levels in many schools below expected, the appetite for enhanced responsibility across the country is mixed. One idea being considered is a national staffing standard. This concerns me greatly. When I was education director in Highland, I could not have staffed small rural and island primary and secondary schools on a national staffing standard. And I may be cynical, but if there’s a minimum standard, is that not precisely the level schools are likely to be staffed to?

Another matter to consider is that there’s no link between raising attainment and higher budgets for schools - the key factors are the quality of leadership and educators. So let’s be clear on the rationale for improved funding for schools, which is needed in certain situations, and ensure that the needs of children and best value for the public pound are priorities.

What’s the best approach? The consultation period lasts until 6 January. No doubt contrasting views will emerge, but the placing of learners’ needs first must be a constant. With that in mind, surely we should take the opportunity to create formal structures around local learning communities (or “clusters” as the consultation paper calls them), including early learning and childcare, and build from there.

The idea of regional education boards is already a live one, but what responsibilities would they have? Is there something appealing in establishing a new grouping of education authorities closely matching the relatively new further education college regions? We could also look at what’s happened in Wales: local authorities still retain some statutory functions, but the school improvement functions - so important for raising attainment - are in regional “consortia”.

Some local authorities are seeking guarantees about local democracy and accountability. There are already different ways of delivering those, of course. Councils would be wise to start thinking about new roles, and to accept that the status quo is unlikely to continue.

My experience of structural change is that momentum can slow down while things change, and some aspirations become frustrations. Some imperatives are undoubtedly about power, control, influence and money, and, with children’s education and families’ aspirations on the line, it’s risky territory.

At all costs, let’s avoid the chaos that is England, where there aren’t even enough school places to go round. The status quo is untenable - but we all should be careful what we wish for from the governance review.

Bruce Robertson is a former director of education

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters