How teachers are working out workload for themselves

Louise Atkinson’s mental health suffered because of her “horrendous” 65-hour working week

“It was that feeling of never being able to complete your list,” the primary school teacher from north Cumbria remembers. “I am a conscientious person and I care desperately about the job that I do. But it was just feeling like you are constantly being flooded with more and more and never being able to complete anything that you’re supposed to do.”

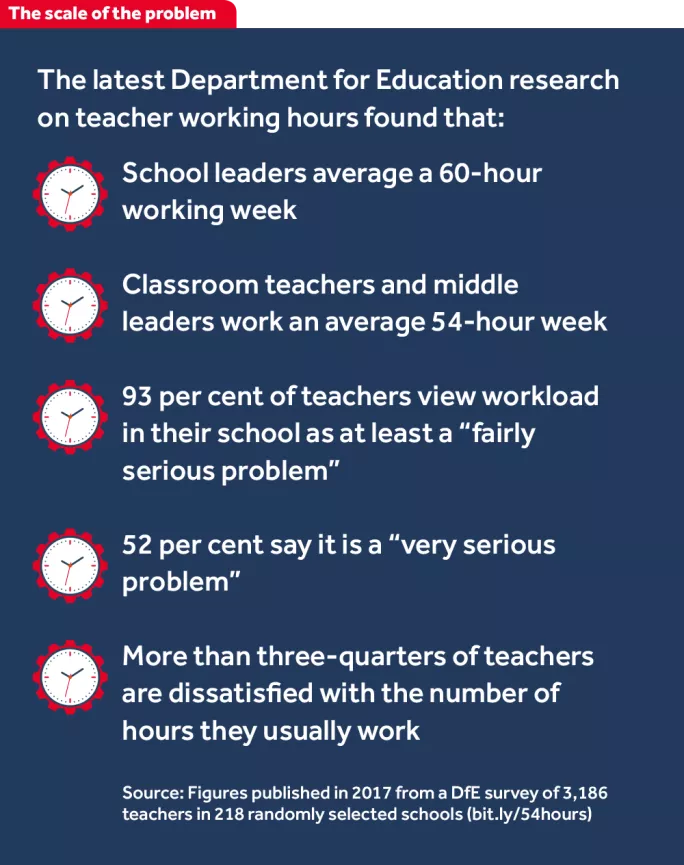

Atkinson’s experience testifies to the slew of data, surveys and reports that all lead to one inescapable conclusion - teachers have too much work to do.

Decisions flowing from government, high-stakes testing, Ofsted, the accountability framework and data collection are familiar refrains from teaching unions discussing the long hours that have become the bane of their members’ frenetic lives.

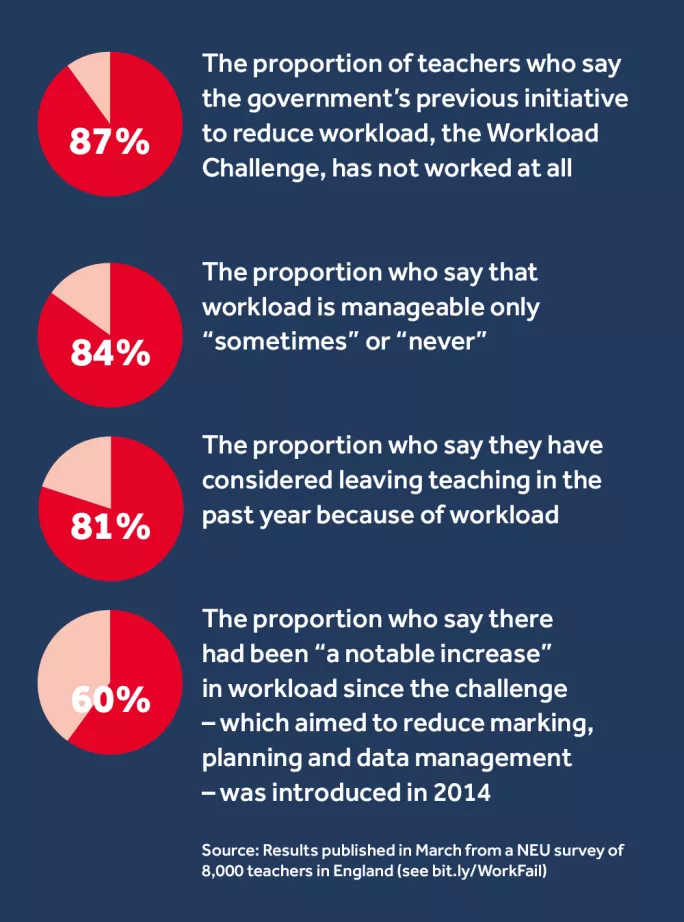

And now, with workload seen as one of the biggest threats to recruitment and retention, the issue is back at the top of ministers’ agenda, too. Fed-up teachers are voting with their feet and the exodus is concentrating minds at Sanctuary Buildings.

In March, Damian Hinds stood on stage at the Association of School and College Leaders’ conference, flanked by the union’s leader and Ofsted’s chief inspector, and became the latest in a long line of education secretaries to promise to do something about the problem - to “strip away the workload that doesn’t add value” (see bit.ly/HindsWork).

He stressed his commitment again last weekend at the NAHT heads’ union conference in Liverpool (bit.ly/HindsNAHT).

Someone is waiting

But classroom unions have been here before - and the biggest of them is giving the education secretary just eight months to demonstrate change before it starts moving towards industrial action.

Maybe this time it will be different. Maybe a streamlined accountability system and an absence of major new assessment reform can quickly cut teachers’ hours. But growing numbers of teachers and schools around the UK are no longer prepared to wait.

With little fuss or fanfare, grassroots solutions to the workload behemoth have been springing up in pockets around the country - and they are starting to have an effect. Never mind ministerial action plans and threats of national action, teachers are starting to do it for themselves.

Nottingham has been a hotbed, and beacon, for such progress. And here, as often happens, the inspiration for a solution was born out of adversity. In 2013, an area-wide Ofsted review of underperforming schools in the Midlands city led to six out of its 14 secondaries being put into special measures, with another identified as having “serious weaknesses”.

The local council responded by setting up an education improvement board (EIB) to raise performance. And it turned to David Anstead - the Ofsted HMI who had just failed its schools - to preside over the development of a strategic education plan for Nottingham.

When the document was sent out for consultation in 2015, almost half those who responded were teachers - and their views turned out to be crucial in setting future priorities in the city. A section of the plan looked at teacher recruitment and retention problems, and all bar one of those who responded cited workload as a cause rather than pay.

A two-hour meeting that the board held with school staff on recruitment and retention pointed in the same direction: little could be done about nationally set pay, but workload could be addressed.

Teachers in the city have judged their collective solution - a “Fair Workload Charter” offering local authority schools a framework to ensure workload is reasonable - a success.

Sheena Wheatley, the NEU teaching union’s secretary for Nottingham and a member of the board’s workload working group, says the aim is to make schools in the area employers of choice, where recruits can expect to work hard but “not pointlessly hard”.

“If you do limit hours, then you have to have a discussion about what are the most beneficial activities in terms of the children,” she says. “It refocuses that discussion in school about, ‘What are we doing for external scrutiny and what work are we doing that actually has a direct impact on teaching and learning?’”

Wheatley says academy trusts in the area have now taken up the idea and are working on their own versions. But the influence of Nottingham’s workload charter stretches much further than that. A growing number of councils in other areas of the country are picking up on this teacher-inspired scheme.

A symposium on workload hosted by Nottingham last year was attended by representatives from virtually every local authority with responsibility for schools. Many, including Coventry, Durham, Oldham and Leicester, are in the process of working out their own versions. Labour’s shadow education secretary, Angela Rayner, is also looking closely at the scheme.

The little things you do together

But teachers don’t always have to turn to their local authorities to get results on workload. They are managing to progress at individual school level as well. In Cumbria, Louise Atkinson’s primary - which she prefers not to identify - is among those grasping the nettle.

When a number of staff manifested work-related stress, and absences went up, the school’s leadership decided to act. They looked at guidance documents from government’s last attempt to get to grips with the problem - the Workload Challenge - and altered work practices accordingly.

Teachers now only do data collection termly, rather than every half-term, and the primary has invested in online resources to help with planning. The school has also looked carefully at its marking policy to ensure it is reasonable, and manageable. The mood is now “much better”, says Atkinson, a NEU school rep.

In Nottingham, the board - mindful of the variety of reasons for high workload cited by teachers - decided to take a different approach, and instead focused on setting a limit on working hours. After much deliberation, Anstead suggested a daily limit of two hours’ undirected work time for teachers, and three for those in leadership roles.

The city’s workload charter also included a set of principles on planning, marking and data collection. The 14 schools that have so far signed up can use an official “fair workload” logo in job adverts to attract recruits, with the reassurance that they will have a guaranteed limit on their working week.

The scheme has backers in powerful places. At its launch in September 2016, Sean Harford, Ofsted’s national education director, was there in Nottingham to reassure heads that agreeing to limited hours would not come back to haunt them in Ofsted inspections.

School were required to review their policies to ensure that they could deliver on their charter commitment. They also had to commit to introducing an annual workload monitoring system, which will be shared with Nottingham’s EIB to demonstrate to teachers that the charter is working.

“It’s too early really to talk about impact on recruitment or retention,” says Wheatley. “But there is anecdotal feedback that staff are really happy about the change and have been engaged in it.

“There are some positive impacts and I think that’s why we are still getting schools coming and saying, ‘We’re interested in this - we want to come and talk to you about it.’”

Sometimes, however, teachers can be their own worst enemy.

Survey feedback from early adopters of the scheme shows that some teachers actually want to do some of things they are now not expected to do, just as happened nationally after the 2003 school workforce agreement.

Wheatley says teachers aren’t stopped from doing what they want to do. But the charter challenges the “unreasonable” notion that they should be working 55-60 hours a week. “Not only is it unreasonable,” she says. “Much of what people are doing is unproductive in terms of teaching and learning, so let’s have a conversation about what we do.”

No life?

Durham’s fair workload charter was created in partnership with unions and local primary and secondary headteacher associations, and with all 268 schools in the county. According to the local authority, its been “widely accepted”. There is also a scheme to help heads manage their own workload and wellbeing.

Claire Taylor, a teacher for 13 years, got a job at a primary school in the county last year and says leaders there are very “conscious” of the charter. She still works a 50-hour week, but says: “It’s less than I did work.”

Taylor is, in fact, one of a fortunate minority. In NEU polling, 60 per cent of respondents said there was “no plan” at their school to cut workload, and only 8 per cent said initiatives had helped to reduce the burden.

But Wheatley says initiatives are now “popping up all over the place”.

“Even the academy chains, whilst they may not want to discuss limiting hours, completely understand that recruitment and retention is linked to staff wellbeing and they need to address that,” she says. “So I think the crisis in recruitment and retention has brought people to the fore who want to try and resolve the issue one way or the other.”

Meanwhile, in Oxford, Michelle Codrington-Rogers, a NASWUT rep who teaches citizenship at a comprehensive, says efforts are being made to ensure that the already considerable workload doesn’t spiral further.

“My school is quite good because when new initiatives come in, one of the things we ask is, ‘If we are going to do that, then what are we going to stop doing?’ I’ve been in the game long enough to say to myself and to other colleagues that if they’re bringing something new in, then we’ve got to stop doing something else.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters