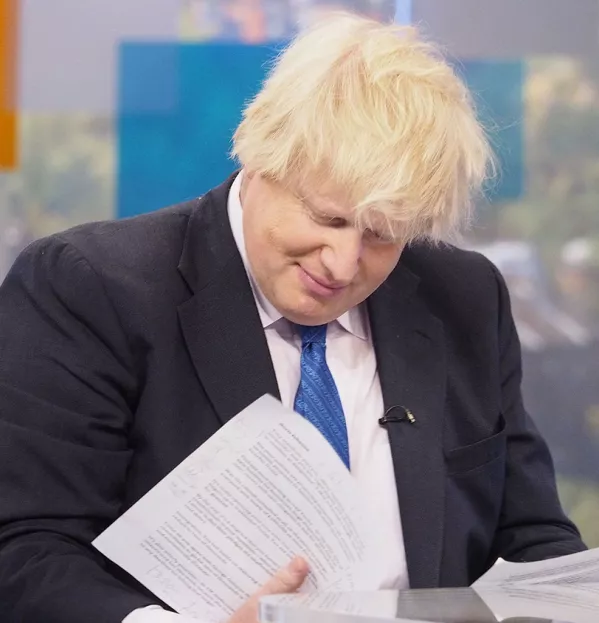

In the run-up to the election campaign, Boris Johnson was caught sneaking a peek at Robert Peston’s notes ahead of a live interview on ITV. The presenter went on to tweet how Boris had been caught “stealing and copying” his “homework”, accompanied by a snap of the “blond bombshell” rifling through the question sheets,

So far, so funny: after all, surely it was just another schoolboy jape from the (apparently) bumbling, gaffe-prone foreign secretary. But it made me wonder how people distinguish between having a laugh and crossing the line. Is cheating ever acceptable?

If Boris were taking his GCSEs, he would undoubtedly have been disqualified. The unacceptability is born of the fact that people who cheat are riding on the backs of those who have done the hard work. Be it cheating in exams or plagiarising chunks of essays from the internet, the outrage comes from those who have done the hard graft; it assaults our sense of fairness that at least equal outcomes can be achieved dishonestly.

Recent figures show a 42 per cent rise in the number of university students cheating in exams with the help of devices such as mobile phones, smart watches and hidden earpieces (see bit.ly/ExTech).

Cheating only postpones failure

Cheating is, of course, particularly frustrating for those who play by the rules; it is unfair to students who studied hard and did the work. Cheating only postpones inevitable failure and the humiliation of being found out.

It’s not just pupils: earlier this year, Ofsted revealed that an increasing number of schools are entering pupils for non-academic qualifications to boost their performance data, which can’t always be in the best interests of pupils. Cheating is plugged into the DNA of many people.

We often turn a blind eye to minor transgressions: we feel indignation and anger at the motorist who pushes in right the end of the lane they have known for 200 metres was due to close, but it soon passes.

But the anger escalates to outrage at the benefit cheat or the tax evader. Cheating the system funded by our taxes is rather more fundamental than queue-jumping.

I guess that is the defining feature of what makes cheating acceptable. When the injury is minor and no-one else is done out of something they value, it is just a lark. When the perpetrator gets something to which they have no right or have not earned, it is a different matter.

Likewise, fake news is just another cheat designed to increase readership or internet click revenue. Fundamental principles of well-researched journalism are compromised by eye-catching headlines or even fabricated stories. Integrity is a word that few really understand.

Honour, truth, honesty, veracity; not words that leap from the Twitter feed very often, but these are the very concepts we seek to instil in our young people. We teach them about the consequences of cheating, but inculcating the values that ensure they know that without being told is a shared enterprise with parents.

For Boris, with his crafty gander at interview questions, it may have been a bit of harmless clowning. But let’s be clear: it was anything of the sort.

Sue Freestone is headteacher of King’s Ely in Cambridgeshire