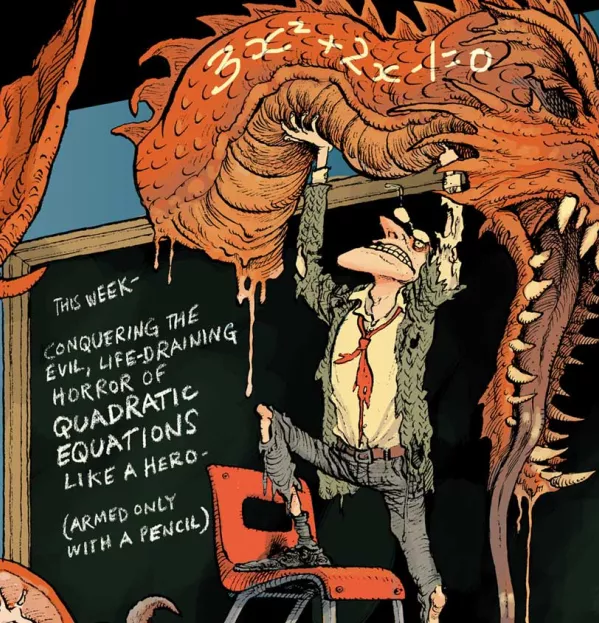

Plot your lessons like they’re Game of Thrones

Since taking over as chief inspector, Amanda Spielman has spent much of her time focusing, quite rightly, on the shape and nature of the curriculum. Whether Ofsted can exert much influence here remains to be seen, especially since it is the Department for Education’s accountability structure, not the inspection framework, that has the curriculum in a headlock. While schools focus on outcomes, it is inevitable that their attention will be drawn to the destination, not the journey.

On the other hand, the removal of levels presents us with a golden opportunity to look again at the curriculum and begin to see it as a narrative, rather than a discrete series of units to be delivered en route to terminal exams.

Anyone who has looked at pupils’ books cannot fail to have been struck by the seemingly random nature of the content of many of them. Science books are full of notes about experiments, with little evidence of the development of skills or attempts to build on prior knowledge; history and geography books jump from topic to topic; and English literature books are often characterised by less-than-dramatic leaps from Tom’s Midnight Garden to Of Mice and Men to Macbeth. One cannot help but wonder what pupils make of all this. To them, the curriculum must seem like wildly random sets of knowledge to be learned and then forgotten.

It is always difficult to urge school leaders to turn away from examined outcomes towards a wider consideration of the purpose of the curriculum, especially if a “good” Ofsted judgement can mean the difference between employment and unemployment. But there are times when leaders have to be brave enough to focus on what really matters. In this case, it is the learning at the heart of the curriculum, not the tests at the end of it. And, of course, if the learning is well-directed, stimulating and relevant, pupils are likely to be better learners and better prepared to demonstrate their learning, whatever the exams throw at them.

Ready, box set, go

In the age of digital entertainment, there is much that we can learn from the way both teachers and pupils consume media content. And the culture of the box set provides an excellent analogy for curriculum design.

First, box sets are extended narratives. Like Years 7 to 11, they often stretch out over extended, five-year periods, with complex narrative arcs and interweaving subplots. They are designed to capture and retain audience interest, and they work hard to ensure that viewers stay with them. Teachers tend to plan the delivery of required content with very little thought to the narrative journey or the need to retain and cultivate their audiences. But there’s a lot to be learned from the likes of Saga Norén, Tyrion Lannister and Tony Soprano.

To design a curriculum that students find engaging, it must be interesting. This is a question not just of content but of teaching styles. In the same way that strong narratives present us with different characters, a range of settings, various twists and turns in the plot, varying pace and shifts from tragedy to comedy, good teaching draws on a wide range of techniques to ensure that pupils are attentive and inspired. Good teaching can undoubtedly help to deliver even the driest subject matter, but a good TV series teaches us that content is a key driver of narrative.

Moreover, the content must be coherent, directed and interlinked. Once we start thinking about the curriculum in terms of narrative, or a storyline, it quickly becomes clear that many of the stories we tell our students are incoherent, disconnected and, sometimes, incomprehensible. Instead of looking at terminal exams and working backwards, we should perhaps think about what we want pupils to learn and then consider effective narratives to sustain their interest.

One useful feature of the box set is the “Previously on …” intro. Far too often, we assume that a topic has been learned before we move on. So why not start lessons with a recap, not just of the last lesson but of those delivered months ago, in the same way that TV dramas often remind us of scenes that happened in early episodes that we need to recall to fully understand what is going on? Checking on pupils’ learning is often left to the summative assessment at the end of the course; regular checks at the start of and during lessons are much more effective in embedding learning. If we are serious about educating pupils, learning needs to be recursive, so that nothing is forgotten and everything is seen as contributing to the storyline.

The most effective box sets feature engaging characters who stick in the memory. They act as anchor points in the narrative, and appear again and again so that we really get to know them. If they are sufficiently developed, they can disappear for weeks on end, yet never leave our memory. Tyrion Lannister, for example, is one of the most prominent characters in Game of Thrones, yet he is absent from the screen for long periods. In the original books, he doesn’t even appear in the fourth novel, A Feast for Crows. Yet we remember him. In each subject area, there are key themes, events, words or skills to which we should return regularly so that, like Tyrion, they engage our attention and stay in the mind.

As viewers, we are always ready to ask the question, what happens now? The best lessons leave pupils asking “What’s next?” and looking forward to later instalments. Narrative theorists refer to this as a “proximal function” - we are led on to the next thing naturally and without any loss of attention. How often, as teachers, do we encourage pupils to think about what’s next so that they are both prepared and looking forward to it? We could even try the odd cliffhanger at the end of the lesson: “If you want to know what’s really clever about this theory, come back tomorrow.”

Some box sets offer us incredibly complex narratives. Anyone who has struggled to follow the twists and turns of the fourth series of The Bridge will appreciate that. Yet, these narratives are not complicated to begin with - they become more complex when we are ready to cope with this and when the scaffold is sufficiently secure for us to grasp what is going on. How effectively do teachers build complexity into curriculum design and how often do they ensure that there is sufficient support to enable everyone to follow what is going on?

Hinter is coming

In a recent blog, Christine Counsell, director of curriculum at the Inspiration Trust academy chain, explores the notion of a narrative curriculum in detail (bit.ly/BlogCounsell). She considers the question of the relationship between key ideas, or learning points, and all the other things that go into making a curriculum enjoyable and engaging. Counsell describes this as the “core” and the “hinterland”. The core could well be the topics a pupil needs to pass an exam, but it is the hinterland - the other stuff they learn along the way - that truly engages their interest.

The battle for the Seven Kingdoms in Game of Thrones may be the story on which the rest of the plot hangs, but it is the characters and events that make the journey enjoyable. The Bridge is fundamentally a crime drama, but it is Saga’s complete lack of social skills that we recall first. In planning an engaging curriculum, it is vital not to underestimate the importance of the hinterland, because it is here that the real learning often takes place.

It is even worth considering the importance of the final credits as part of the box set analogy. Praise is a vital part of the learning process, but how effectively do we integrate opportunities to acknowledge good work into our curriculum planning?

Finally, we also need to think beyond our own subject, and in cross-curricular terms. Amazon provides food for thought here: “If you enjoyed this, you’ll really like this.”

It may be sad to relate that, according to a recent survey, 64 per cent of people would rather watch a box set than read a book, but we must acknowledge the power of a medium that can engage the attention of mass audiences by delivering narratives as complex as those provided by Shakespeare or Dickens. If teachers could develop curricula as powerful as box sets, think of the possibilities. Ygritte’s withering remark in Game of Thrones, “You know nothing, Jon Snow”, should perhaps be the starting point.

Richard Steward is headteacher of the Woodroffe School in Lyme Regis, Dorset

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters