“What makes a book silent?” may sound like the start of a Christmas cracker joke, but it’s a question that staff and students at the University of Glasgow’s School of Education have been trying to answer, using “silent books” on loan from the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY).

Also known as wordless picturebooks - the “silent” comes from the Italian translation - this travelling exhibition comes after a collection assembled in 2012 by IBBY members across five continents, part of a powerful response to the influx of refugees on the tiny Mediterranean island of Lampedusa. The touring version aims to bring these stories and experiences to a broader audience.

What makes these books silent is their wordlessness or predominantly visual nature. With the stumbling block of printed text removed, readers of all ages, stages and tongues engage with the images in ways that seem more fluid, open-ended and democratic. That is not to say the books are culture-free: many offer insights into other ways of being and doing, which are simultaneously similar and different to our own.

Rich and diverse in content, the books deal with themes including war and childhood (The Rocket Boy by Ara Jo), migration (The Arrival by Shaun Tan), animals and the environment (The Tree House by Marije and Ronald Tolman) and even the trials of jam-making (Bramenjam by Natascha Stenvert). All celebrate the power of images to cross linguistic barriers and cultural divides: to promote important literacy practices and understandings about narrative, while providing vital spaces for imagination, empathy and hope.

Potential parity

For teachers, research has demonstrated the potential of these books to create increasingly level playing fields for readers on either side of a language barrier, or for those who struggle to decode written text. They can also help develop empathy by encouraging pupils to engage with facial expressions and body language, as well as the use of colour, shade and symbolism. And they can help develop higher-order thinking kills and critical literacies by forcing young readers to read in between the lines in new, creative and visual ways.

We have enjoyed sharing these books with staff and education students, especially those on our MEd in children’s literature and literacies. We have been introduced to new models of storytelling, while recognising the vast number of quality texts that have literally become “lost in translation” because of the current publishing climate and dominance of Western texts.

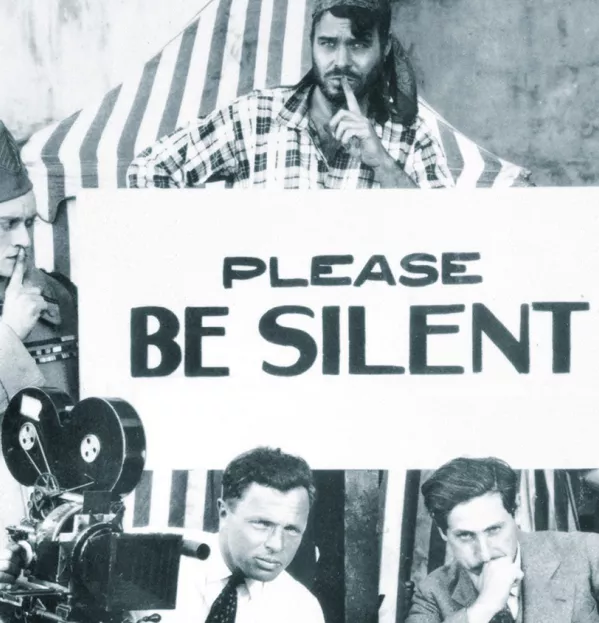

As ironic as it sounds, we have also discovered that silent books are quite noisy. The drop-in sessions and workshop we organised to allow readers time and space to browse and discuss were filled with conversation, brow-scratching and exclamations - but most loudly of all, laughter.

Evelyn Arizpe is senior lecturer in children’s literature at the University of Glasgow