TAs: superheroes sold short

Even if Megan Charlton had been the only teaching assistant (TA) in County Durham to go on strike late last year, it would still have hit her school hard. Megan, a higher-level teaching assistant (HLTA), single-handedly plans and teaches all the French lessons, among many other duties. Without her, things would have got complicated.

But Megan was not alone. About 1,800 other TAs working for the county also went on strike in November. And it didn’t just put schools in a difficult position, it closed them.

“The council thought of us as being pot-washers who worked for a bit of pin money,” she explains. “But you’re never doing things like putting up a display or washing paint pots now - if children are in school, you’re working directly with them.”

This seems to have come as a surprise to Durham County Council. The strike was called over a new term-time-only contract that would have cut TA pay by up to 20 per cent. A decision on that contract has now been suspended until September while the council undertakes “a review of TAs’ role, function, job description and activities… to establish whether current job descriptions adequately describe the role being undertaken”.

It’s a process everyone in education, not just Durham County Council, needs to undertake. Without anyone really planning it, TAs have changed almost every aspect of school life. Where once they were feared as a threat to the teacher role, they have slowly become an essential additional part of every classroom. So much so that, as the Durham strikes showed, schools cannot run without them.

The transformation has come with little official recognition, support or financial progression. If TAs continue to be neglected, Durham will surely be the first of many clashes. Which means that the profession needs to collectively decide what it wants TAs to be and how to support them, and quickly.

On a wing and a prayer

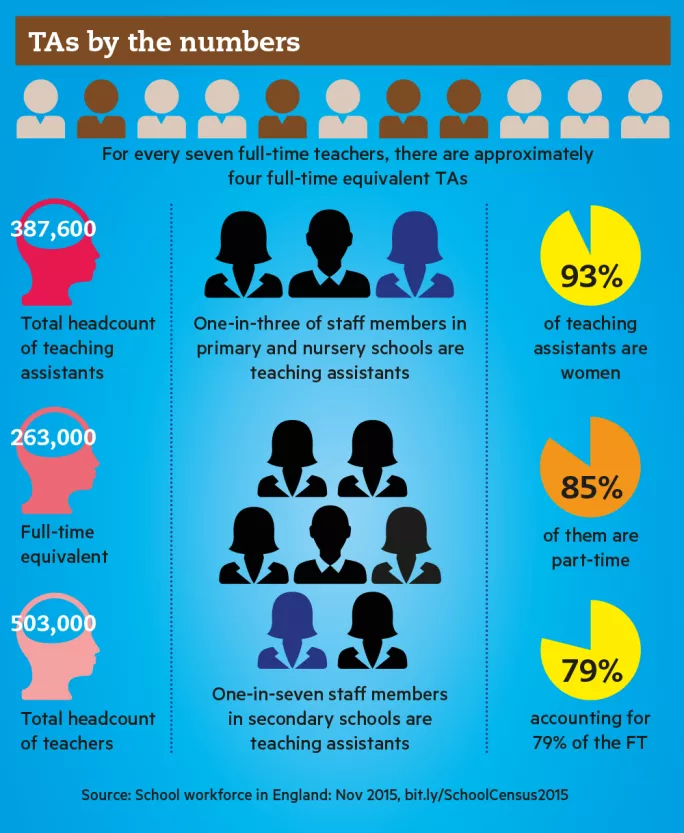

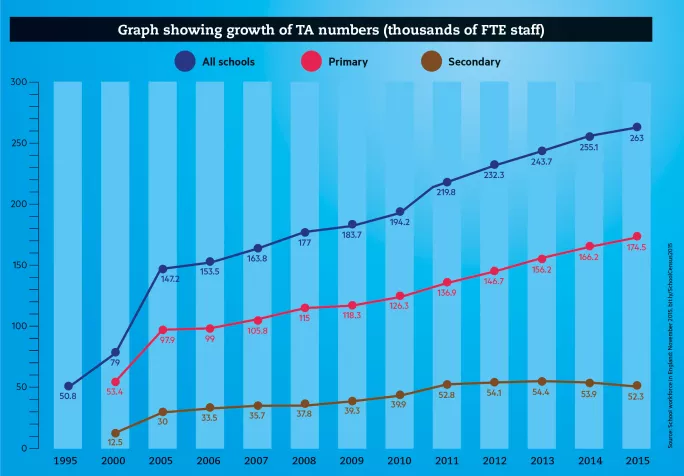

Today, 44 per cent of full-time equivalent classroom roles in primary schools are TAs (a term that encompasses teaching assistants and HLTAs, as well as other similar classroom support roles) rather than teachers. In secondary schools, the figure is about one-in-five. Back in 1995, some 50,000 full-time-equivalent TAs were employed; today, the total is 263,000.

Rob Webster, a researcher at University College London, who began his career as a teaching asssistant, describes the evolution of the TA role as “wing and a prayer stuff”.

He co-authored the Deployment and Impact of Support Staff (DISS) project in 2009, which was the first study to systematically examine over five years how the growth of support staff had affected schools. Teachers’ workload and stress had improved, it found, but TAs were doing far more than taking on admin tasks: their role had changed, and they spent most of their time supporting low-attaining pupils and those with special needs. With less attention from the teacher as a result, the progress of those pupils suffered. The report suggested ways to improve the use of TAs. Unfortunately, says Webster, the government failed to use the findings to finally define the role and support the development of TAs.

“Since [the DISS project], there has been no policy response at all,” he says. “It’s been rather left to schools to decide.”

So the numbers of TAs continued to rise without any central plan for how they would be used. Professional standards for TAs, which would have set an expectation for CPD among support staff, were finally commissioned by Liberal Democrat MP David Laws, then schools minister, in 2014, but they were never officially published. Asked if there was a policy in place, a DfE spokeswoman said: “It is up to individual schools to decide how to train, develop and use their TAs effectively.”

The council thought of us as being pot-washers who worked for pin money

Similar logic was deployed in 2010 when Michael Gove decided to scrap plans for a national pay spine for TAs and the national standards for the role of higher-level teacher assistants were archived.

Unison - the union that represents TAs - has warned that there is no consistency to the HLTA role, with many TAs doing work that previously would have been the preserve of HLTAs.

The DfE spokeswoman also referred to the DISS research and work by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF).

Given the lack of official guidance, Webster and other researchers, unions (including Unison) and schools have taken on the challenge of defining professionalism for TAs - taking it upon themselves to publish, revise and disseminate the unpublished government professional standards.

And thanks to the likes of Webster, who is running a new EEF trial in 100 schools called Maximising the Impact of Teaching Assistants, we know that TAs can be beneficial for students. He says the evidence so far is clear that TAs have a measurable positive effect if they’re used correctly.

“TAs should supplement what teachers do, not replace them,” he says. “[But] teachers quite often use TAs to compensate for something that they’re not confident with or that they don’t feel able to do.”

Managing a TA

What, then, does TA best practice look like? Webster’s research, and that of others, points to several strategies:

* TAs can help students to progress by an extra three to four months over an academic year when they run specific interventions one to one or with small groups. Training is crucial: typically, TAs need five to 30 hours’ work with experienced teachers before they’re ready to lead an intervention.

* Teachers then need to fully understand the content of interventions, so that they can help students to apply and consolidate their progress back in the classroom.

* Another key component of effective use of TAs is ensuring they are prepared for the lesson. Many schools are building in extra time for TAs to liaise with teachers. Such routine collaboration makes it easier for teachers and TAs to swap around, so that students spend time with both adults during the week, as well as working in groups and independently.

* Finally, research has also shown that improving the way that TAs talk to and question students, and encouraging them to focus on what students learn rather than merely completing the task, can improve a student’s independent-learning skills.

Some schools are already demonstrating elements of this best practice, including Fairburn Primary School in North Yorkshire.

Following research, and with the agreement of TAs (including payment for the extra time), headteacher Emma Cornhill changed TA contracts to add 20-minute handover times at the beginning, middle and end of the day, so that they could be brought up to speed on planning and share feedback. Training sessions are organised to ensure that staff efficiently pack everything they can into these handover sessions. Teachers’ planning also explicitly includes what to do with their TAs.

Teachers and TAs also have longer weekly meetings for more wide-ranging discussions about what has been done and what should be done next.

“I am a teacher, I still teach, and we had never been trained on how to manage a TA in the classroom,” explains Cornhill. “You’re just thrown into it.”

Now, she says, the school does a lot of team teaching. This responsive teamwork has eliminated the need for explicit interventions for struggling students.

It’s an outcome that St Mary’s Church of England Primary School in East Barnet has also arrived at. The school has introduced policies similar to those at Fairburn and seen positive results.

“There isn’t an association that the TAs only work with the children with special needs or low-ability children - we work very hard to distribute the support and ensure that every child has a right to work with their teacher across the week,” says deputy head Maria Constantinou.

How widespread are strategies such as these? It is difficult to tell, but there is certainly agreement that they are not widespread; the Durham example highlights how far policy and guidance is behind the reality of TAs on the front line.

The lack of recognition and awareness - along with the variations in how schools use TAs - will increasingly become an issue. For example, Webster says that growing special educational needs and disability support requirements will expose bad practice in the use of TAs, and children will suffer if schools do not get it right.

The thing that really pees people off the most is when we get our payslips and it says “non-teaching staff”

“The special-school sector is facing a huge challenge. It’s not just the numbers but the complexity of need,” he says. “We need to make sure TAs know their roles, and TAs and teachers all fit together like jigsaw pieces; interlocking and complementing each other.”

The recruitment crisis brings another perspective. “It’s a crisis,” says Colin Harris, a retired headteacher, who now works as a consultant. “But it would be worse if it wasn’t for the quality of the TAs that we have.”

An ATL survey earlier this month of more than 1,000 TAs corroborates this - it found that 78 per cent were covering classes in the role of a teacher.

“That reliance will need to grow; the only way that can happen is if we begin to better define, support and reward TAs,” Harris says.

Lessons from healthcare

How, then, should the role develop, assuming the impetus existed to find new solutions? Here, it’s useful to look to healthcare - a sector that faces economic pressures similar to education: rising staff costs and the need to maintain essential face-to-face contact makes it hard to improve productivity.

To meet these pressures, new support roles are continuing to emerge in healthcare: nurses are being given greater responsibility by doctors, healthcare assistants are taking on the more menial tasks and the government is creating new nursing associates as a role to fit in between. This sounds a bit like an HLTA, but of course they would more guidance and a proper framework nationally.

Similarly, there may be space for a range of teaching and pastoral support roles in schools to free up teacher time. Based in a deprived area of Bristol, The Bridge Learning Campus has as many support staff dedicated to pupil welfare as it has TAs. Even candidates with qualified teacher status are applying.

The TA role could also develop into a training route: a source of a ready and willing supply of would-be teachers.

Keziah Featherstone, headteacher at The Bridge Learning Campus, is currently funding a TA to gain a science degree through the Open University and become a qualified teacher. She says that many schools are looking for ways to train up their own teachers. Creating an apprenticeship programme for TAs, leading to a higher-level apprenticeship for teachers, could be one way of doing that, she suggests.

Growing your own staff has its advantages over hiring an external candidate. “You’re taking a huge gamble on somebody that shines on one day of interview [wth external candidates]. And they’re going to have a massive impact on your school,” she says.

The ideas set out above need more research to see if they are the best ways forward and, if they are - or if they throw up alternatives - official backing will be required if best practice, proper definition and development is to become widespread and successful.

But while the research is moving apace, official backing seems unlikely, considering the government statement above. Without a national programme, TAs will continue to struggle for recognition, schools will suffer and incidents such as the strikes in Durham will become more commonplace.

Megan Charlton, the Durham TA, says that her local NUT union secretary suggested the TA role might be better described as “assistant teacher”. Yet when she receives her monthly payslip, she is reminded that officials’ eyes need to be opened if they are to see the role in the same light.

“The thing that really pees people off the most is when we get our payslips from the county and across the front it says ‘non-teaching staff’. It really riles people to call us non-teaching staff when that’s what we do.”

It may seem like a symbolic point but it’s more than that: while our education system depends on TAs, it misrepresents their work and undermines their job security. Isn’t it time we faced up to the truth?

Joseph Lee is a freelance journalist @josephlee

Life as a TA

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters