Things will never be the same again

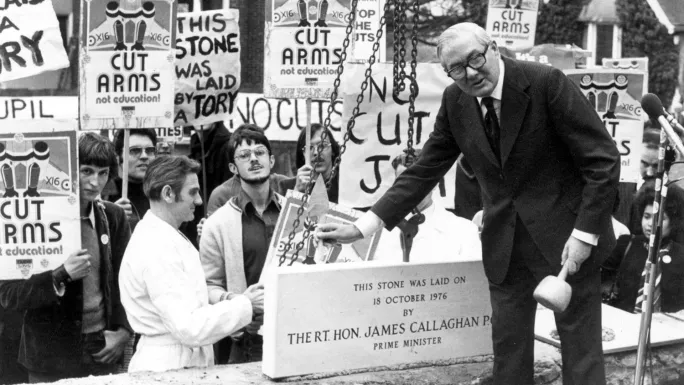

The turning point in modern British educational history was exactly 40 years ago this month. On 18 October 1976, at Ruskin College, Oxford, James Callaghan, who was prime minister at the time, delivered a landmark speech about schools policy. Nothing in education has been the same since. The professional destinies experienced by headteachers and teachers today in 21st-century classrooms were set when Callaghan stood up to speak.

Believe it or not, before that autumn day, prime ministers and their education ministers did not meddle in the day-to-day work of schools. Until then, the public debate on education was limited to inputs: the number of pupils staying on until school-leaving age, the number of schools, the kind of schools, teacher numbers and training. For example, Margaret Thatcher, education minister from 1970 to 1974, is remembered for the White Paper A Framework for Expansion, closing more grammar schools than any other minister and abolishing free school milk. All about inputs.

But after Callaghan’s speech, the debate became about outcomes: were schools effective and, if not, how could they be improved? What knowledge and skills were needed and how might they be acquired? And, not least, were standards of achievement high enough for the modern world? It was a decade or more before the shift in focus was reflected fully in the 1988 Education Reform Act, but it was precisely this shift that made such legislation possible. All about outcomes.

‘Ripples of interest’

News of Callaghan’s speech had been leaked in advance of his trip and controversy had been whipped up. So it was with some trepidation that the prime minister began.

“There have been one or two ripples of interest in the educational world in anticipation of this visit. I hope the publicity will do Ruskin some good and I don’t think it will do the educational world any harm. I must thank all those who have inundated me with advice: some helpful, others telling me less politely to keep off the grass…It is almost as though some people would wish that…[the] purpose of education should not have public attention focused on it, nor that profane hands should be allowed to touch it.

“I cannot believe that this is a considered reaction. The Labour movement has always cherished education…There is nothing wrong with non-educationalists, even a prime minister, talking about it now and again.”

With characteristic understatement, Callaghan was challenging the consensus that education should be left to the teachers. He was also making history; prime ministers prior to that time simply didn’t make major set-piece speeches about education. For most, it wasn’t of sufficient priority; for others, a minefield to be avoided.

The new priority

When, a few months earlier, Callaghan had told his (eminently forgettable) education minister, Fred Mulley, that he intended to make this speech, the minister “rather blanched”. That September, Mulley was reshuffled and the rather more famous Shirley Williams took his place. This reflected the new priority.

At Ruskin, Callaghan was now getting into his stride. He marched into the disputed terrain.

“I do not join those who paint a lurid picture of educational decline…although there are examples which give cause for concern.”

This was another of Callaghan’s intentional understatements. He had only become prime minister in April that year and, right from the start, he had intended to do something significant about education.

Along with John Major, he is one of only two post-War prime ministers not to have attended university. It grated with him throughout life. He passionately wanted to use his new position of influence to improve education. And he knew the education system was letting large numbers down.

Callaghan wanted to use his new position of influence to improve education

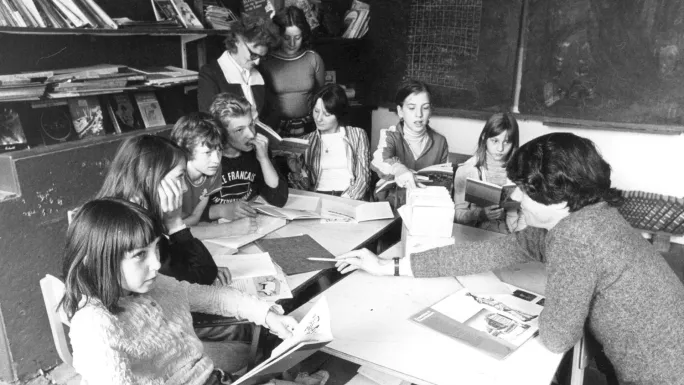

That July, in a blaze of publicity, Sir Robin Auld QC had published his enquiry into the bizarre goings-on at William Tyndale Primary School in Islington. There, the headteacher, Terry Ellis, had tested the limits of professional autonomy. No records were kept and pupils were allowed to do what they liked. The result was anarchy.

Ellis brazenly fended off his critics. He told one governor that he “did not give a damn about parents”, “teachers were pros at the game”, and “nobody else had any right to judge them…In any case, parents were either working-class fascists or middle-class trendies.”

The Auld Report slammed the Inner London Education Authority. The absence of even the most basic accountability for outcomes had allowed the madness at William Tyndale.

In spite of this sea of troubles, Callaghan remained resolute; standards mattered. So, cautiously but firmly, Callaghan took up this theme in the speech: “In today’s world, higher standards are demanded than were required yesterday and there are simply fewer jobs for those without skill. Therefore we demand more from our schools than did our grandparents.”

An impressive orator in his own way, he warmed to his theme. “There has been a massive injection of resources into education…But in the present circumstances, there can be little expectation of further resources being made available…I fear that those whose only answer to these problems is to call for more money will be disappointed…There is a challenge to all of us…to secure as high efficiency as possible by the skilful use of existing resources.”

In other words, school effectiveness was now paramount. The prime minister himself had worked on the text over the weekend, softening the draft that his policy unit head, Bernard Donoughue, had provided. In his diary for Wednesday 13 October, Donoughue marked the occasion: “The press is speculating that Jim is going to come out with some revolutionary statements about going back to the ‘3Rs’. So we had to tear up the original draft…and write the ‘major’ speech which the press expects.”

And, it should be added, which the prime minister expected, too. Donoughue relished the opportunity in honest language that echoes right to the present day, adding: “This is a marvellous chance to feed in some of my personal prejudices.” Both he and Callaghan believed strongly in the “3Rs” and traditional teaching.

For a prime minister to raise these issues at the time was sensational

Hence the next paragraph of the speech. It looks mild in retrospect, but for a prime minister to raise these issues at the time was sensational.

“Let me repeat some of the fields that need study because they cause concern. There are the methods and aims of informal instruction; the strong case for the so-called ‘core curriculum’ of basic knowledge; next, what is the proper way of monitoring the use of resources in order to maintain a proper national standard of performance; then there is the role of the inspectorate in relation to national standards; and there is the need to improve relations between industry and education.”

The post-war settlement, which left the “secret garden” of the curriculum (and teaching methods) in the hands of teachers, was over. Indeed, the future is foreshadowed, clause by clause, through this paragraph: the germs of the national literacy and numeracy strategies, a national curriculum, national testing, a strong Ofsted and, finally, city technology colleges, academies and the importance of employability.

The long game

Historically, the most interesting question is not just the impact of Callaghan’s speech but also why it took so long to take effect.

When I interviewed him years later, Callaghan remembered, “By God, we had to fight for it.” The education department was totally in thrall to the defensive teaching profession.

Years later, Callaghan reflected on what he perceived as a failure to follow through the Ruskin agenda. He might have blamed his ministers but preferred to be self-critical: “I rather blame myself…I wish I had been able to spend more time on education… I was determined not to let the economic thing overshadow everything…but in fact we were engulfed.”

But that was far from the end of the story. At Ruskin, Callaghan warned the teaching profession of impending danger.

“To the teacher I would say that you must satisfy the parents and industry that what you are doing meets their requirements and the needs of our children. For if the public are not convinced, then the profession will be laying up trouble for itself in the future.”

In short, embrace accountability or it will be imposed on you. That this turned out to be prophetic will not be lost on modern-day teachers.

Callaghan warned the teaching profession of impending danger

Yet in the 1980s, teachers resisted accountability at every turn and became mired in a series of strikes over pay. By the middle of that decade, the education system had become a battlefield, with young people the main casualties. The teacher unions missed the significance of the cool Ruskin breeze; instead, they reaped a whirlwind that transformed their landscape.

Kenneth Baker’s 1988 legislation brought the introduction of a detailed national curriculum and national tests at four key stages. It was followed, in quick succession, by the publication of school-test results and the creation of Ofsted in its modern form. Governments began to use new powers to intervene directly where outcomes were poor, initially at Hackney Downs School.

This is the point I find myself becoming part of the story. I was directly involved in the closure of Hackney Downs in 1995 (it was, years later, to become the now-renowned Mossbourne Academy). The following year, I was preoccupied with preparing a national literacy strategy for primary schools. And in 1997, after Tony Blair’s election victory, I took responsibility, in the Department of Education, for its implementation, along with a parallel strategy for numeracy and interventions in poor schools and local education authorities. In many ways I became the manifestation of the Ruskin agenda.

In the middle of all this, I interviewed Callaghan for TES to mark the 20th anniversary of his now famous speech. Inevitably, we made the connection between Jim’s aspirations then and what Blair was planning to do if elected. He was thrilled at the prospect of a Labour government, which would demand high standards and prioritise education in a way that he had never been able to do.

When Kenneth Morgan’s magnificent biography of Callaghan was published shortly afterwards, Jim signed my copy, thanking me for my role in “plotting Labour’s course on education” and having been “an unfailing help” to him whenever he asked. Touched, I knew then that I had inherited the torch lit at Ruskin College and could not let him down.

If he were with us now, Jim Callaghan would no doubt be inspired by countless teachers and schools across the country. For teachers themselves, the biggest change since Ruskin has been a move from autonomy in their individual classrooms to constantly improving their practice, in collaboration with colleagues. Meanwhile, the vast majority of school leaders have embraced accountability and thrived accordingly. In effect, the Ruskin spirit infuses everything.

Forty years on, Callaghan has been vindicated. Inputs will always matter, but educational outcomes are firmly on everyone’s agenda - exactly as he would have wished.

Sir Michael Barber is a former education adviser to Tony Blair’s government. He is now chief education adviser at Pearson and author of How to Run a Government

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters