The truth about testosterone and oestrogen

Other than dying, I think puberty is probably about as rough as it gets.”

This quote, attributed to the Australian singer Rick Springfield, will no doubt resonate - especially with those of you who spend your working lives in the company of adolescents.

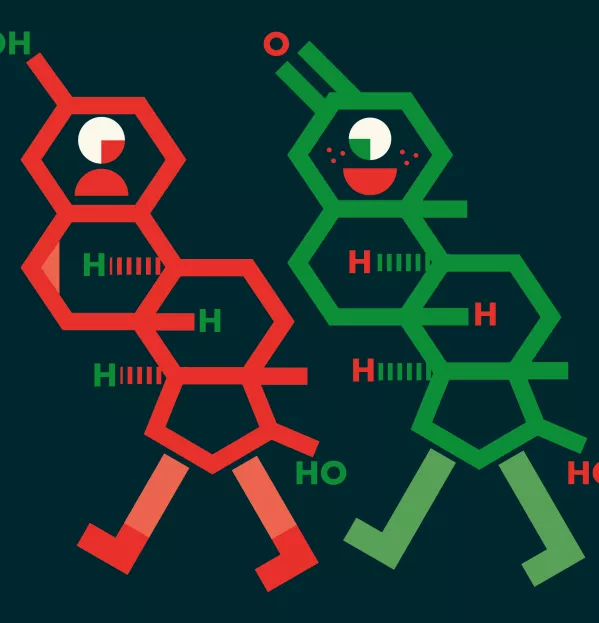

The teenage years are a time of huge physical and mental change, played out in the hyper-focused school environment. And two of the most influential biological components cited in this process are the sex hormones testosterone and oestrogen.

But how much do we really know about their impact on the behaviour, viewpoints and social sense of teenagers?

It is difficult to avoid the conventional wisdom: that testosterone is all about aggression (think silverback gorillas beating their chests in a bid to secure alpha-male status), while oestrogen production is closely related to menstrual cycles, and can lead to unpredictable emotional variations.

These perceptions, however, give anything but the full picture.

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone in men. It plays an important role in physical transitions, such as the development of the penis and testes and a deepening of the voice.

Oestrogen, meanwhile, is significant in the development of women’s bodies. In pubescent girls, it plays a role in the development of fallopian tubes and the uterus, and also causes breasts to grow. There are actually several types of oestrogen in the body, but the widely used word “oestrogen” generally refers to the strongest hormone, oestradiol.

Beyond these basics, several myths have become popularised. For example, one is that testosterone is only crucial in the development of men, and male-associated behaviours. Although men typically have about 10 times as much testosterone than women, it is still very much present in girls. Likewise, oestrogen is also produced in both men and women, but is more significant in the development of female bodies.

“Higher levels [of testosterone] are related to being further along in development, or more mature. [And] it’s a precursor of oestrogen - it is ‘converted’ into oestrogen and can therefore have similar effects in both sexes,” explains Anna Tyborowska, who researches affective neuroscience at the Donders Centre for Cognitive Neuroimaging and Behavioural Science Institute, based at Radboud University in the Netherlands.

Another myth is that puberty begins when the physical signs of it becomes visible, usually in the early teens. In fact, it lasts a lot longer.

“The first phase, when the adrenal gland is maturing, is already starting in seven- to eight-year-old girls, on average, and in eight- to nine-year-old boys,” explains Jiska Peper of the Brain and Development Research Centre at Leiden University. “You cannot tell by their physical appearance that these young children are in puberty yet, but their hormonal glands are very active.”

Researchers are only just beginning to examine the impact of oestrogen and testosterone on behaviour at this stage of child development.

“Preliminary evidence suggests that [these hormones are] related to symptoms of depression and anxiety in both boys and girls,” Peper says. “I believe it is important that teachers are aware of these early pubertal markers from 8 years old onwards.”

Interestingly, beyond the above, we actually don’t know with any certainty many of the effects oestrogen and testosterone have on teenagers.

For example, it is accepted that testosterone has a role in the huge changes in the brain that occur during adolescence, a process that’s described in Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore’s book Inventing Ourselves: the secret life of the teenage brain. The increase of pubertal testosterone is thought to help drive this second period of intense neural development during adolescence; the first takes place in early childhood. But quite why or how testosterone plays a role, we are yet to find out.

During adolescence, explains Tyborowska, there is a shift towards more prefrontal control, which facilitates the development of emotional control. “However, the mechanisms of how testosterone actually acts on the brain and drives these changes still need to be investigated,” she says.

Similarly, testosterone’s impact on behaviour is a lot less clear-cut than the alpha-male stereotypes would have you believe.

Studies in animals suggest that testosterone does have a role in shaping the brain circuits related to certain social behaviours. And previous studies, including work carried out in Tyborowska’s lab, suggest that the higher testosterone levels during early- to mid-adolescence are related to the brain processing emotional control in a more adult-like way.

“In other words, higher testosterone levels were [associated] with more activity in regions [such as] the prefrontal cortex - regions that are activated when emotions need to be controlled in adults,” she says.

Towards the end of adolescence into the beginning of young adulthood, however, things seem to change, and testosterone becomes associated more with social dominance, and sometimes the aggressive behaviour mentioned previously.

But at what specific age this happens is highly variable.

“It’s important to keep in mind that, especially during early- and mid-adolescence - around ages 11 to 14 - teenagers vary considerably among each other with respect to timing and speed of pubertal development. So, age becomes less of a proxy for maturity, when one 14-year-old can be quite different from another with respect to how mature they are.”

The second sex hormone

We know even less about how oestrogen impacts on behaviour. While it is widely believed that oestrogen is closely linked with emotional wellbeing, exactly how or why this occurs is not well understood.

“Most of the research that is investigating sexual hormones during puberty and adolescence is about testosterone, because it’s easier to get a reliable measure than oestrogen,” explains Corinna Laube, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Development Centre for Lifespan Psychology at the Max Planck Institute in Germany. “What is key, though, is that during puberty, both sex hormones rise in both genders.”

Kate Steinbeck, endocrinologist and medical foundation chair in adolescent medicine at the University of Sydney, led a research team that performed two systematic reviews of the research on the impact of puberty hormones - both testosterone and oestrogen - on mood, wellbeing and behaviour in adolescents. The evidence, she agrees, is limited.

“Well-designed longitudinal studies over years are needed to answer these questions, and these are not yet in the literature,” she says. “We need to remember that while these puberty hormones rise to adult levels at the end of puberty, [they] stay at these levels during adulthood and many of the behaviours attributed to them disappear.”

This begs the question: what other factors are at play?

“Hyper-emotionality, impulsivity and sensation seeking are driven by the parts of the brain that reach mature status earlier than the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for…abstract and long-term reasoning, decision making and assessment of risk,” Steinbeck explains.

This part of the brain does not reach full maturity until the mid-twenties, she says. “While puberty hormones may play a role, it would appear that many of the classroom behaviours are primarily driven by the maturing brain.”

Adolescent behaviours are also commonly an extension of behaviours learned (or not learned) in childhood, she says.

“The way parents parent their children in the first decade will certainly influence how their children behave in adolescence,” Steinbeck concludes. “Learning to control emotions is something that needs to be taught and modelled throughout childhood, so that when adolescent neurocognitive changes occur, the flare-ups and impulsive words or actions are better able to be managed.”

How schools could help

So the common occurrence of blaming hormones for how teenagers behave is clearly far from accurate, and actually not very helpful. But could the knowledge we do have about the impact of testosterone and oestrogen give us any indications about how we can better support teens in schools?

One thing the academics reiterate is the need for tolerance, or a better understanding, of why teenagers may display behaviour to impress their peers, gain people’s respect or bump themselves up the social ladder. The link between all of these things, says Peper, is a testosterone-powered appetite for risk taking.

“We do see a relation between testosterone production in teenagers and forms of risk-taking behaviour,” she says, adding that this correlation is observed in boys and girls.

“Risk-taking behaviour has traditionally been regarded by teachers and parents as annoying,” she continues. “However, a certain level of risk-taking behaviour is necessary for teenagers to discover the world. In fact, if a teenager does not take risks at all, he or she may miss out on making friends, discovering their identity [by] trying new hobbies or hairstyles and so on, or learning new skills - which all require risk-taking.”

Laube adds that the testosterone-driven desire to improve social status wins out over any potential dangers.

“They just want to kind of get a higher social status in their group, they just want to be taken seriously, and that’s very important for them,” she continues.

This leads on to another testosterone-linked piece of advice: Laube says adolescents will respond better when they are given respect, and feel they are more on a level with the person instructing them.

“Interventions that treated young people with more respect actually were found to work better,” she says.

Laube’s research has also suggested a link between testosterone levels and a need for immediate gratification. While no causal link was established, her study on boys aged 11 to 14 suggested that levels of the hormone had an impact on her subjects’ sensitivity to immediate rewards.

Unfortunately, the way the education system is set up - with final grades only being awarded at the end of a year or term - does not cater to this, she says: “Often, children have to wait too long for their reward.”

Finally, Peper also thinks it is worth teachers considering how testosterone reacts to teacher interactions.

“It is important to note that testosterone can be affected by positive feedback,” she explains. “For instance, a compliment by a peer or teacher…can increase testosterone temporarily, which reduces feelings of depression. Moreover, boys with high testosterone who are given the feeling of high status are inclined to obey rules.”

How easy would all this be to put into practice with the myriad other factors at play? Across this three-part series, we have also seen how “stress hormone” cortisol and “pleasure chemical” dopamine play their part in how teenagers behave - just the complexity in those two areas is enough to make your head hurt. Add in the above and teaching teens may seem impossible.

And yet these three biological factors are interacting with millions of other variables - some biological, some social, some from other origins. It just goes to show how hard a teacher’s job really is. Trying to understand and unlock the secrets of testosterone, oestrogen, dopamine or cortisol can help to guide teachers, but it is unlikely to offer solutions.

So why do people do this seemingly impossible task? Because that complexity is so rewarding, because learning about things like how testosterone impacts on the body is so fascinating and because teenagers are so endlessly enjoyable to be around, argues Steinbeck.

“Not everyone finds working with adolescents enjoyable,” she admits, “but their enthusiasms, their ability to think outside the square, their creativity and their altruism are some of the characteristics [that] make working with them such a profound experience.”

Chris Parr is a journalist and education writer

This article originally appeared in the 22 March 2019 issue under the headline “The truth about teenage hormones”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters