Why teachers should avoid labelling students and instead have high expecations for all

It began with rats. For experimental psychologists, it often begins with rats. Rodents are favoured because they have relatively simple neurological systems, they’re easy to get hold of and they don’t tend to complain all that much. In many ways, they’re the ideal subjects. Except, in the case of Robert Rosenthal’s experiment in a Harvard University basement lab in 1963, it wasn’t actually the rats he was experimenting on. It was the rat handlers.

Robert Rosenthal is the psychology professor who would make his name studying “expectancy effects” and what became known as the “self-fulfilling prophecy”: the idea that, if we expect a certain thing to happen, sometimes just expecting it is all it takes to make that thing come true.

He would develop his ideas by conducting one of the most controversial experiments in the field of education - lying to teachers and cheating kids. It was all in the name of science, of course. And what he discovered had far-reaching and hugely important implications for anyone in education.

But, first, the rats. Rosenthal’s idea was to see if, by priming his research students with a single piece of information about the rats they were experimenting with, it would make a difference to the way the rats behaved.

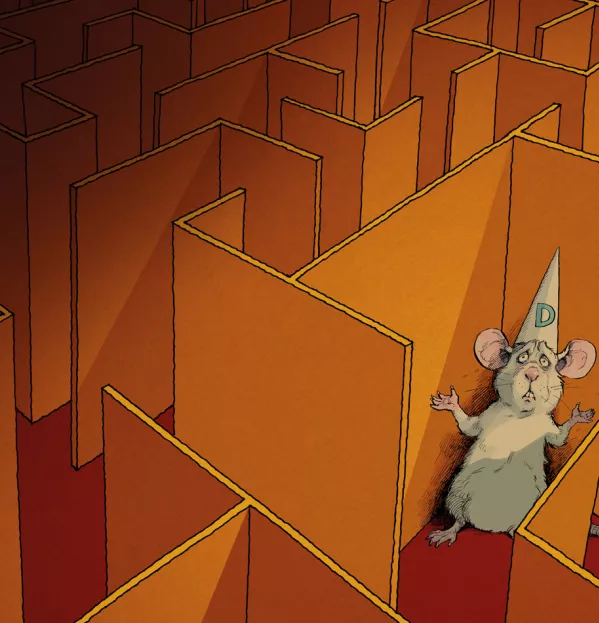

The experiment involved telling his lab team that a group of rats had been specially bred to be one of two types - either “maze bright” or “maze dull”: better or worse at navigating the lab maze. The trick was that the rats were identical and had been randomly assigned to the two groups by Rosenthal - a crucial fact kept secret from the researchers.

The rats were put through their paces in the maze. When the results came in, it was found that the “maze bright” rats had actually got through the maze faster. It appeared that the researchers’ beliefs about their subjects had created a genuine effect.

Had the rats picked up on the positive expectations of their handlers? Had the handlers given them more encouragement, leading to the improved performance? Or had the researchers just subconsciously doctored the results to meet expectations? Whatever it was, Rosenthal knew the next question he wanted answered. He wrote about the discovery in a 1963 article in American Scientist: “If rats became brighter when expected to, then it should not be far-fetched to think that children could become brighter when expected to by their teachers.”

The American Scientist article was read by the principal at an elementary school in San Francisco, Lenore Jacobson, who wrote to Rosenthal soon after it was published: “If you ever ‘graduate’ to classroom children, please let me know whether I can be of assistance.”

That was all the invitation Rosenthal needed. A few months later, he was all set to find out if the performance of a bunch of schoolchildren would be so easily affected by their “handlers”.

The set-up for the experiment was straightforward, if decidedly sneaky. With only Rosenthal and Jacobson in the know about the true nature of the experiment, Rosenthal came to Oakwood Elementary School and explained his research to the school teaching staff. He told the staff that the students were going to take a test: the Harvard Test of Inflected Acquisition, specially designed to identify which students were about to undergo a significant leap forward in their intellectual capabilities.

Bogus information

In fact, the test was a standard a IQ test, and the 65 children who were identified as the “intellectual bloomers” (the equivalent of the “maze-bright” rats) were picked entirely at random. Once the bogus information had been disseminated to the teachers, Rosenthal left them to it.

He returned to the school eight months later and had all the children retake the IQ test. Just as predicted, the randomly selected “bloomers” scored higher than the other students. They had, indeed, bloomed. By simply giving the teachers a single piece of information about their students, Rosenthal had created a very real effect.

Rosenthal titled his research paper “Pygmalion in the Classroom”, named after the Greek legend of a sculptor who falls in love with one of his creations until his obsession brings the statue to life.

“Pygmalion in the Classroom” had a huge impact when it was first published, with Rosenthal making the front page of the New York Times and ending up as a guest on the Today Show with Barbara Walters.

It was also hugely divisive. The research was attacked by other psychologists for its ethical and theoretical failings. And it was attacked by the education profession, who took issue with the very clear implications of Rosenthal’s work: if kids were failing at school, it wasn’t because of a lack of resources or their deprived social backgrounds, it was because the teachers weren’t treating them right.

So, what was going on? Rosenthal’s explanation tapped into a concept that was very much in vogue in the social sciences at the time, the power of labelling. The sociologist Howard S Becker, regarded by many as the founding father of labelling theory, had shown just how pervasive the process of labelling was within the education system. Becker’s research in schools had suggested that teachers all have in their minds their own version of the ideal pupil.

As teachers, we have to take notice of this idea for a few good reasons. First, we all label our students - whether we mean to or not, it’s an inevitable social process. (Don’t feel too bad about this: the kids do it to teachers, too). Second, once a label’s been applied to a student, it can be remarkably resistant to change. Third, as Rosenthal showed, labels have important real-world effects.

One of the problems with the labelling process in schools is that we attach labels to our students based on all manner of unhelpful signifiers. Gender and ethnicity are obvious candidates, but a name, an accent or even clothes can all consciously or unconsciously start to see us assign characteristics to a student. This is such an ingrained human process that we can’t stop ourselves from doing it, but we should at least be aware that it’s occurring.

We also need to recognise that, in many cases, the labels may be preventing us from seeing the whole picture. If we’re not careful, the outcome is clear: we put in more time and effort for the kids with positive labels, and we make life harder for the ones with the negative labels. It’s not a comfortable thought, but any teachers who don’t recognise they might occasionally act this way probably aren’t being honest with themselves.

No one is immune from labelling

So, what can we do about it? Do teachers just have to think good things about their students to make them succeed? Forget interventions and five-part lesson plans - according to Rosenthal, all teachers need to do is expect the students to do well and results should go through the roof.

The truth’s a little more complicated, but there are certainly some important things we can learn from Rosenthal’s work. The first thing is to accept that labelling occurs - no one is immune.

Once we’re aware of our tendency to attach labels to students, we can try to use the process for the good of our classes. The goal must be to tap into whatever processes led the 65 bloomers in Rosenthal and Jacobson’s experiment to bloom.

Rosenthal identifies four key factors: four ways the students with the positive labels were being treated differently, which allowed them to make more rapid progress.

The first difference experienced by the positively labelled students Rosenthal calls “the climate of the classroom”. This is the mood or atmosphere created by the person holding the expectation and experienced by the student. Climate can be communicated verbally, by positive comments, a cheery “hello” or a “well done”. Or it can be communicated non-verbally: smiling and nodding more often, providing greater eye contact and so on. When the climate of the classroom is pleasant for students, it’s that much easier for them to enjoy and engage with the work.

The second difference is the amount of feedback provided to students. The students expected to achieve more tended to receive more frequent and more valuable feedback on their work, such as more detailed targets or a wider range of follow-up questions. Conversely, for students where less might be expected, feedback for good work might be limited to a tick and a smiley-face sticker.

Third is the level of input teachers give to the favoured students. Teachers tend to reserve more work - and more demanding work - for the students they think are going to be able to handle it. This is a tricky issue to get right because, of course, teachers often need to differentiate - there’s little point in asking a bottom-set Year 7 English class to provide an analysis of why Mrs Dalloway is a finer example of modernist literature than Ulysses.

But we shouldn’t be scared of throwing challenging work at the students whom data tells us can’t cope with it. In our data-obsessed world, it might be heresy to suggest it, but sometimes the data gets it wrong.

Finally, Rosenthal identifies output as another way that teachers push the students they perceive to be brighter. Teachers encourage greater responsiveness from those students from whom they expect more. They give them longer to think about a question before moving on to another student; they push them to elaborate on an answer; they demand longer and more complex responses to homework assignments.

I contacted Professor Rosenthal a few years ago to ask him a question that my A-level sociology students were always asking, whenever we studied his research: weren’t the teachers really annoyed when they found out they’d been duped?

He wrote back to tell me that the teachers had mostly been pretty good about the whole thing. He’d gone on to say, however, that they’d all been surprised that he’d needed to conduct the study at all. If he’d wanted to know whether labelling affects students, why didn’t he just ask the teachers, they said. They saw it happen every day.

So maybe that’s the lesson. Experienced teachers know that they label their students. And they know that those labels can have a profound effect on how those students perform. The trick is to keep in mind that the labels we attach to students may not be a good reflection of who they are. We need to think about where the labels came from originally. Was it something we heard from a colleague? Or maybe from one incident in the first week of term.

Teachers need to be willing to reassess how they see their students. We should try - as hard as it may be sometimes - to give them another shot at being the ideal pupil we have in our heads. We need to think of all of our students as having the potential to be the maze-bright rats. Even on the days when they just seem like rats.

Callum Jacobs is a supply teacher in the UK.

This article originally appeared in the 3 JANUARY 2020 issue under the headline “Always check the labels”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters