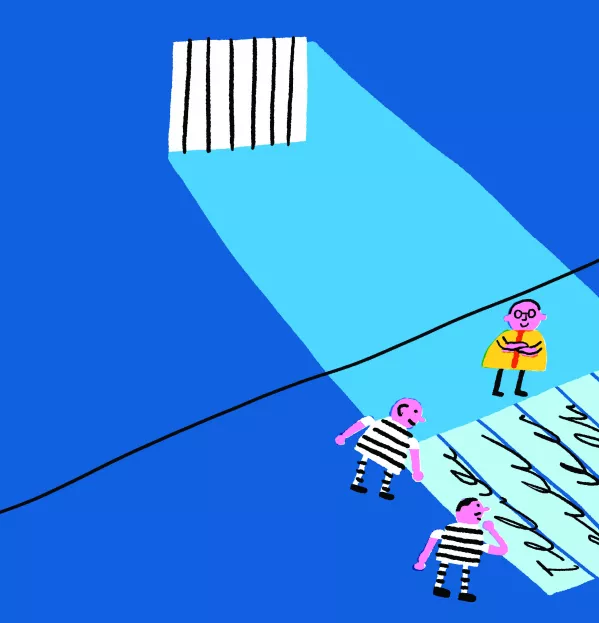

Lessons from prison education

For more than a decade, Kirstine Szifris was fortunate enough to work with some of the sharpest academic minds in the country. After leaving the University of Sheffield with a first-class degree in maths, she moved to the University of Cambridge, where she gained an MPhil and, eventually, a PhD in criminology.

But it wasn’t in these bastions of academia where Szifris learned the most, it was while teaching in prison. “In six months engaging prisoners in discussions about philosophy, I learned more about the world, and how to live, than in 10 years of study at Cambridge and Sheffield,” she says.

Szifris, now a research associate in the Policy Evaluation and Research Unit at Manchester Metropolitan University, is one of the thousands of educators who teach in the UK’s prison network.

Her experience makes it clear that, while this much misunderstood sector brings obvious challenges for educators, it can be enormously productive. If you can teach in prison, you can teach anywhere - and prison educators could have some useful lessons for their counterparts in schools and colleges.

‘Big gaps in the research’

According to the Education Support Partnership, there are 124 prisons in the UK, each with between 10 and 50 teachers. Ostensibly at least, prison education typically operates like a mini further education college.

There is variation between settings, but the education on offer is likely to focus on vocational, skills-based qualifications and courses alongside functional skills: literacy, numeracy and ICT. Beyond this, there is likely to be provision for art teaching, one or two classes at level 3 (A levels or equivalent), and the opportunity to take a distance-learning course through the Open University.

While mainstream education has been the subject of a string of research-based interventions, the question of how to overcome the challenges faced by prison-based teachers has not been studied as intensely. As part of a research partnership between Manchester Metropolitan University and Novus, one of the largest providers of prison education, Szifris was part of a team that looked into how much empirical, verifiable work had been done to investigate prison-based pedagogy.

“We did a huge review of the literature to find out what was out there and, unfortunately, the answer was ‘very, very little’,” says Szifris. “There are some really big gaps in the research. Prison education is massively under-theorised and under-researched, especially in the context of how it relates to change, and identity and desistance.”

It is an area that requires urgent attention. In 2016-17, Ofsted rated 44 per cent of prisons as “requires improvement” or “inadequate” for their education provision. And figures show that, one year after being released from prison, only 17 per cent of offenders have found a job.

According to Jane Hurry, a professor of the psychology of education at the UCL Institute of Education, the principle issue is translating proven teaching approaches from more mainstream educational settings into the prison environment.

“To a great extent, it isn’t exactly rocket science,” says Hurry, who is researching the role of prison education in men’s post-prison transitions to employment.

The first challenge is matching the needs of the students to what is being taught, she explains: “Most education programmes and qualifications in prisons are at level 1. While it is true that prisoners tend to have lower than average English and maths levels, as many as half are already at level 1 or above, and should therefore be going for GCSE or above.”

This is a familiar problem for Jose Aguiar, head of teacher training at East Surrey College. He has spent more than 10 years teaching in prisons, and is currently delivering a number of programmes at Pentonville Prison in London.

The learners he encounters vary hugely. “Some students are 20 years old, and others are 40 or 50,” he says. “Some need to learn basic maths or English, but how do you teach 25- or 35-year-olds what they are supposed to have learned when they are 8, 9 or 10? You can’t teach them in the same way as children. In the same class, you can have a guy with a degree.

“It is about how we can enable everyone to learn, regardless of these differences. In mainstream education, you have to address differences - but these are really big differences.”

Aguiar adds that, while mainstream education is usually structured around the age of pupils, this is simply not possible in prisons, not least because the definition of “age” is by no means set in stone: “You sometimes have guys with an academic age of 10 or 11 but with a ‘street’ age of 30 or 40 and a biological age of 19. So the teaching approaches need to be different - they are in an environment that is not particularly conducive to learning, and it is also optional.

“It is a task that means we must be much more creative in how we approach teaching.”

This, however, is far more easily said than done. As Gerry Czerniawski, a professor of education at the University of East London, notes in his 2015 paper “A race to the bottom: prison education and the English and Welsh policy context”, the European Commission has highlighted a number of challenges facing prison education across the continent. These include overcrowded institutions, increasing diversity in prison populations, the need to keep pace with pedagogical changes in mainstream education and the adoption of new technologies for learning.

What is prison education for?

One of the big challenges is identifying precisely what role, or roles, prison education should be fulfilling. Should it primarily be focused on the kind of practical, vocational training that might lead to employment? Or should it seek to improve prisoners’ academic credentials - again, with a view to boosting employability once they serve their term?

“There are two fundamental assumptions to the link between making prisoners employable and reducing their criminal behaviour outside,” Szifris explains. “One is that prisoners are feckless - that they came to prison with no education, no qualifications, and having never had a job.”

This is simply not true. “Something like one in five of the prison population have an A-level equivalent qualification or above,” Szifris continues. “About 50 per cent had a job in the year before incarceration.”

The second assumption is that prisoners turned to crime for financial reasons. “While that is true for lots of people, it is not true for huge swathes of the prison population. In the case of sex offenders, for example, their crimes are not financially motivated, so having a job or not probably doesn’t relate to their criminal behaviour.

“As much as helping prisoners to become more employable is important, that only deals with a certain proportion of the population. Some prisoners do lack skills [and] have very low literacy - and functional skills qualifications are great for them - but some of the population are not catered for.”

Szifris’ research suggests that prison education should focus on personal development, and more innovative ways to improve relationships with peers and family members. “That can come through reading groups, philosophy groups, art or music,” she says. “That is the kind of argument that is being made now by the small number of us doing research in this area.”

The full picture of what these approaches might look like is still emerging, but there is anecdotal evidence about what works well away from classes that are more suited to the traditional “chalk and talk” approach.

Morwenna Bennallick has just completed a PhD in learning cultures in prisons, funded by the Prisoners’ Education Trust. She also teaches university-level criminology modules in several prisons, and is all too aware of the challenges facing educators who are looking to introduce more innovative approaches to education in prisons.

“People are coming to you having experienced really high levels of educational trauma in their past - they’ve often been excluded [from school],” she says. “They are coming to education for the first time in a long time, and often not necessarily out of personal motivation but because the prison has told them to. The most significant and fundamental task of a prison educator is establishing trust.”

‘You can’t deliver a lecture’

In short, prison educators are charged with engaging some of the most disengaged learners imaginable - and earning their trust in order to facilitate that engagement is one of the most critical parts of the job. Research suggests that there are several ways to do this, and Bennallick says the key is “really focusing on active, participatory lessons”.

“You cannot deliver a lecture and give out worksheets and hope it goes well,” she explains. “There has to be a real commitment to getting feedback immediately, getting people to talk about their opinions, and making people realise that nothing bad is going to happen.”

Like Szifris, Aguiar has been involved in innovative prison education programmes that he believes demonstrate the value of more creative approaches to prisoner education. In his case, this involved introducing a 12-week drama course to a prison via a project with the London Shakespeare Workout charity, culminating in a performance.

“Because the course was conducted in a male prison, the female roles had to be taken by men - which was actually just like going back to how Shakespeare was originally performed,” Aguiar says, adding that this was an educational experience for some.

“Obviously, in prison, ‘masculinity’ can be very important. There is a lot of diversity and a lot of people with cultural backgrounds that are quite homophobic. To see some of those guys engaging was extremely rewarding - it was quite a transformation.”

There were other benefits, too. Aguiar invited representatives from the theatrical and film industries to the show. Some prisoners ended up going into that line of work after finishing their sentences. “Some of the guys [who performed] were identified [as talented], and when they were released, they were engaged to appear in some films, adverts and small plays. These were guys who had never considered this,” he says.

For Szifris, the subject matter is philosophy. Her PhD research, carried out at the University of Cambridge’s Prison Research Centre, explored the impact that philosophy can have on prisoners’ personal development.

“The idea is to engage prisoners in philosophical conversations,” she says. “It is not about reading Descartes or Plato’s Republic - although, sometimes, you do sit down for the class and it turns out the prisoners have already read more philosophy than you have. It is more about engaging them in Socratic dialogue.”

This is a more informal, peer-driven approach to education than you might expect in a jail. Szifris has delivered the course, which typically lasts about 10 to 12 weeks, in a number of settings, including a high-security prison in the North of England, where some of her students were serving 20-year terms.

“We spend a few hours a week talking about philosophical ideas, like ‘What is society?’ or ‘What is identity?’, and then we might put forward Plato’s ideas about society and engage them in a dialogue.

“One of the reasons why it works is that the [prisoners] get the opportunity to articulate themselves. Over that period, you can build up trusting relationships between the prisoners, which is quite rare in prison. Prisons have a complex hierarchy, but you can get people from different factions in the same room together.”

Breaking down ‘brick walls’

Szifris’ research indicates that the course helps relationships, and improves prisoners’ open-mindedness and self-articulation. These are all things that are relevant, she says, to desistance: the cessation of offending or other antisocial behaviour.

“The best thing about it is that it’s accessible - you don’t necessarily need to be able to read or speak English particularly well,” she adds “I have had classes of people who have never engaged with education before sitting alongside university professors who are teaching, or others with an Open University degree, and it allows them to relate to each other and understand each other better.”

Prisoners, Szifris says, are often natural philosophers. “Research shows this, especially if they have long sentences. They have been ripped out of their environment and placed in a completely separate social group - it can be very unsettling. So, some prisoners are often very reflective, very philosophical.”

Despite the undeniable successes of such programmes, Aguiar says it can still be a challenge to get more innovative forms of teaching on to the prison curriculum.

“I come up against a lot of brick walls. Sometimes it can be difficult to set these projects up; there are security issues in bringing people from outside in,” she says.

“But I am proud that we have been able to do it and make this happen in a very challenging environment.”

Chris Parr is a journalist and education writer

This article originally appeared in the 29 March 2019 issue under the headline “How prison education creates windows of opportunity”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles