Schools - don’t be slaves to data, says governor

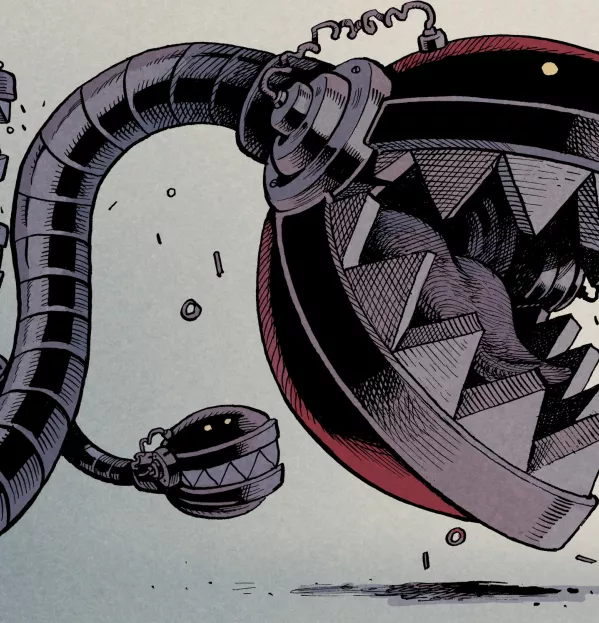

I threw a small hand-grenade - in the shape of an unexpected agenda item - into a recent quality and standards committee meeting. I know, radical. But revolutions all start somewhere, and often from very small sparks. In this case, it was at a governors’ meeting at a rural primary school in Derbyshire.

My metaphorical hand-grenade came in the form of proposing that we might ditch data altogether. Of course, we would have to record statutory data, such as for phonics and Sats. But for everything else, I suggested, we should use teachers’ experience, expertise, judgement and intuition.

What surprised me was how vigorously the use of data was defended by our staff governor. I hadn’t got him pegged as a counterrevolutionary: he is a young and excellent teacher who delivers outstanding results and is very highly regarded by children, colleagues, parents and governors alike (indeed, he is known in some quarters as “the child-whisperer”, such is his ability to maintain order without raising his voice). I expected him to leap at the chance to divest himself of data obligations and launch into an idealistic dream of pedagogic purity. But no, he was distinctly discombobulated. He displayed an attachment to data that I had not anticipated.

It was only then that I realised the extent to which data has become a security blanket for some teachers. And, to be fair, anyone qualifying in the past decade or so was handed this blanket even as they threw off their university gowns, so no wonder it seems alien to imagine teaching life without it. The current obsession with data has been with us for some time, and new teachers will have been immersed in it, will have conversed in it and are now cursed with it. It’s all they’ve ever known. It’s what they’re judged on. No wonder they want to cling on to it.

Subsequent conversations confirmed that our young staff governor was not alone. Teachers coming through in the past decade or so have known that numbers dictate success, failure, progress and, ultimately, their livelihood. We are reaping the harvest of what successive governments and Ofsted hierarchies have sown.

As chair of the school’s quality and standards committee, I regularly receive various documents packed full of data from the senior leadership team. For each meeting, we have pages of numbers, graphs, diagrams, arrows, gauges and dashboards. It’s nothing out of the ordinary and has become a staple of our meetings. We study the data, we interpret the data, we ask questions about the data, and we discuss how the data should influence policy and practice. In the last meeting, when I added my final agenda item, I also provided a link to an article I had read called “Against metrics: how measuring performance by numbers backfires” (bit.ly/DataBackfire).

I’ve long been concerned at the extent to which data drives school leadership and governance, and this article seemed to pick out some key arguments about being driven by metrics, about the danger of replacing professional judgement with numerical indicators of comparative performance based on standardised data, and about trying to motivate people by attaching rewards and penalties to their measured performance. It allowed me to articulate for the first time why I have always found the primacy of data unsettling.

Data is meant to help governors. It is meant to make everything more transparent and allow us to ask tough, searching questions of the leadership team. It is meant to clarify where we are, where we’ve been and where we’re going. It does no such thing.

Enormous assumptions

Government guidance to governors says that “by having regular sight of key data, this will enable you to establish the ‘root causes’ behind the problems and drivers behind success” (see bit.ly/GovernorData).

This smacks of something that sounds great as long as you don’t spend too long thinking about it. It also makes enormous assumptions about the definitions of “problems” and “success”.

For example, what if a school has been dealing with a child who has been late, who has often tried to run away, whose behaviour has led him to the brink of permanent exclusion? And now, after huge effort, patience, compassion and careful discipline, he has started to stay in class, to do a little work, to not hurt other pupils. More importantly, for the first time, he has been experiencing some stability in his life; he has been feeling some form of safety and security at school and he is beginning to understand that he is worthy of love.

That, to me, is a monumental achievement. How does he appear in the data when the governors gets their spreadsheets before the meeting? He shows up in red against lateness, unauthorised absence, reading, writing, Spag and mathematics. He is a problem: the school has a problem.

This is an example of the dissonance at play between what we, as governors, as a school and as a society, say we want schools to do for young people and what data-driven governance actually encourages in reality.

Another example: I particularly love it when teachers bring something to our school that they enjoy doing - be that a sport, music or other interest - and share it with the children. For our pupils to learn something new, discover a passion or simply to find a space that makes them feel special and valued is as important as delivering the curriculum. But that doesn’t fit on a spreadsheet.

Last week, my daughter’s year group put on an interactive exhibition on the topic of Iceland. She worked for weeks on her contribution, went to a friend’s house to build a geyser (complete with vinegar and bicarbonate of soda for realism), spent hours researching and typing up information, and came home daily with fascinating facts. The exhibition was brilliant: four rooms full of creativity, understanding, enquiry, enthusiasm, new-found confidence, camaraderie, great writing, beautiful drawings, brilliant games, spectacular models and beaming faces.

In my committee meeting, how would that have been represented in the data? It wouldn’t. Yet that kind of event, for me, is fundamental to the formative school experience.

There is another disconnect between what we say and what we do regarding risk and reward. We want to encourage children to take risks, to innovate, to try things, to overcome this very modern fear of failure. But what are we asking our teachers to model? Well, we want extraordinary results but no risk, please, if you don’t mind. Failure shows up in the data, and we can’t have that.

Similarly, there’s a disconnect between what we tell children and what we model in the way we encourage them to become independent thinkers and problem-solvers while at the same time stifling the entrepreneurial instinct in their teachers.

Data-centred, not child-centred

Of course, I understand that one of my primary tasks as a governor is to hold the school to account. This is now done almost entirely through the medium of data. It is such a reductive way to look at things, especially when we are dealing with young individuals with all their successes, failures, hopes, fears and foibles. We often talk about maintaining a long-term view and accepting that children have their periods of great progress but also times when they get stuck. In the long run, it doesn’t matter. But if this shows up in the data, it feels as though we are not holding senior leaders properly to account.

Equally, we accept that it is wise to target interventions on a small group of children in a class purely because they are on the cusp of a shift from one arbitrary attainment level to another (that is, they might move from working at the expected level to working at greater depth). Another child does not receive the same treatment. This is not child-centred, it is data-centred.

I know this is the norm in most schools because all schools know they are judged on data. I would not criticise anyone taking this approach: they are simply responding to the system. The danger, though, is that what we end up doing in our governor meetings is interrogating how well the teachers are gaming the system. Actually, as governors, are we failing in our basic role of providing challenge to the head if all we do is fuss around the edges while fundamental questions go unanswered, indeed, unasked?

As an aside, it’s worth noting that the things many of us parents value the most - happiness, kindness, resilience, tolerance, determination, empathy, fulfilment, and so on - are largely unmeasurable.

I’m well aware that I’ve said all this with the gay abandon of someone who is not a teacher. I know it’s a damn sight easier to have a radical view when I’m not immersed in the everyday reality of teaching. I also accept that while high-flying, confident, creative teachers might seize the freedom from data and fly, newly qualified teachers who are short on confidence and reliant on structure might hate it. I guess what one person sees as a straitjacket holding them back, another sees as scaffolding holding them up.

Our headteacher - who is open to the idea of ditching data - did also point out to me that we were now in the relatively privileged position of being a “good” school doing reasonably well. Fair point.

But still, I want to know what all this data is for. My favourite question to ask senior leaders in discussions around data is, “Did this tell you anything you didn’t already know?” By and large, the answer is “No”.

So why the need for data? What difference does seeing a 0.5 per cent shift in a number from one month to the next really make? And, importantly, why are we treating data as gospel when, more often than not, it’s simply someone’s educated guess about how a certain pupil or group of pupils are doing at one particular moment in time?

After all, while I know there is a need for scrutiny and accountability, doesn’t the appraisal of teachers and the senior leadership team serve that purpose sufficiently?

We seem to be caught up in a cycle of mediocrity, where high ambitions are compromised by the restrictive setting of a data-driven education culture. Sure, we’re moving forward as a school, we’re doing great things for our children both academically and non-academically, but it feels as though, to access the next level, we have to break free.

However, I fear that the sustained pressure from government to raise standards on reduced budgets, allied to the consistency demanded by multi-academy trusts keen to demonstrate their efficacy, will increase the likelihood of data continuing to rule the roost.

So what am I to do as a governor? It’s easy enough to continue interrogating statistics. The catch-22 is that data is exactly how schools are measured by the vast majority, including government and parents. Is my primary responsibility to the short-term ambitions of the school and the staff, neither of which have much of a choice but to fit in with a data-driven environment? Or is it to the pupils, to broader society and to the future into which we hope to send out more humane, generous, confident, broad-minded agents for change? Is it absurdly grandiose to think one school can redefine what successful education looks like?

Well, I’m going to keep asking the question. At least if we’re going to stick with the status quo, it will be by choice. Most revolutions, even if they fail, at least get people thinking about whether there might be a better way.

Nick Campion is co-vice-chair of governors at Hilton Primary School in Derbyshire

This article originally appeared in the 8 March 2019 issue under the headline “Who wants to break free from data?”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters