- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- The surprising ways exercise can improve your teaching

The surprising ways exercise can improve your teaching

As always, it’s been a long day: back-to- back lessons, lunch duty, a whole-staff meeting at 3.30pm, followed by a couple of hours of marking.

After battling the rush-hour traffic to finally reach home, you’re totally sapped of energy.

You had promised yourself you’d go for a run, but right now, it’s the last thing you want to do. Surely, you’d be better off just collapsing on the sofa to recover. Right?

Maybe not, says Andrew Jones, a professor of applied physiology at the University of Exeter. He explains that, at the end of a physically inactive working day, our minds feed us a misleading “perception of tiredness” that can only be corrected by exercise.

In fact, he points out, you’re far more likely to feel re-energised, motivated and happier as a result of pushing ahead with that run.

“Exercise elevates the heart rate, increasing the rate at which oxygenated blood goes to the brain, where hormonal changes are also occurring. It’s the release of endorphins and dopamine that is so good for mental health,” says Jones.

But teachers are active, aren’t they? Unlike many office workers, they’re on their feet all day. No one could describe a teacher’s working day as “inactive”, surely?

Teacher wellbeing: How regular exercise can benefit teachers

Jones argues that while teachers spend a lot of time standing up, they don’t actually move around a lot. This, he says, is problematic.

“It’s really a question of gravity. Leg muscles contract and relax like pumps efficiently returning blood to the heart when we walk. But when we stand still, blood pools in our lower legs and feet and our hearts have to work harder to recirculate it,” he says. “It’s why soldiers pass out when they’ve spent too long on guard duty.”

If you’re spending big chunks of time standing at the board, circulating the class every now and then won’t be enough to counteract this; more intensive exercise is needed to make a real difference to energy levels.

But if exercise can make us feel happier and more energised, why does it take so much willpower to make us put on those running shoes at the end of a long day?

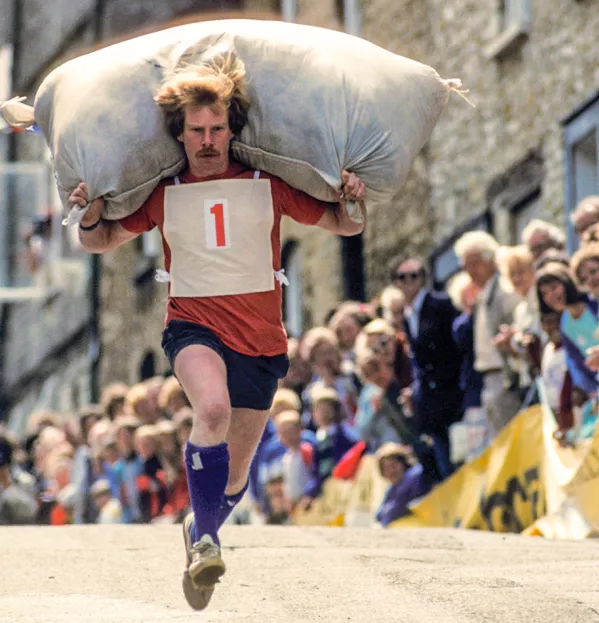

According to an influential theory developed by David Raichlen, professor of human and evolutionary biology at the University of Southern California, the answer has been encoded into our DNA by our ancestral past as hunter-gatherers.

Many anthropologists believe that humans evolved to hunt by chasing down and exhausting their prey over long distances. Raichlen hypothesised that the so-called “runner’s high” that people experience following moderate and intense aerobic activity might be a “neurobiological reward” for the high energy costs and injury risks associated with this endurance approach to hunting.

If this was the case, he argued, we would see the same reward pattern occurring in other animals that hunt over distances.

In a 2012 study, Raichlen put this theory to the test by looking at neurotransmitters called endocannabinoids (eCBs), which appear to play a major role in generating the so-called runner’s high by “activating cannabinoid receptors in brain reward regions during and after exercise”.

Raichlen and his team measured circulating eCBs in humans, dogs (an animal adapted to run) and ferrets (an animal not adapted to run) before and after treadmill exercise.

They found that in both humans and dogs there was a significant increase in eCB signalling following high-intensity exercise. Ferrets, on the other hand, showed no such increase. This, Raichlen argues, might explain why humans and dogs habitually engage in aerobic exercise, while animals like ferrets avoid such behaviours.

So, humans were born to run. But modern life, for all its benefits, has brought our species to an unnatural standstill and now most of us lead relatively sedentary professional lives - with our physical and mental health paying a high price.

What can be done? Is the solution for teachers as simple as regular exercise?

Jones, who helps endurance athletes to maintain energy levels, improve performance and extend their careers, believes teachers first need to become more “self-aware” about their levels of activity. This means regularly taking a couple of minutes to reflect on when they were last properly active. If the answer is days, weeks, or months, he recommends introducing an “exercise snack” in which a teacher encourages the whole class (themselves included) to stand up and jump on the spot for a few minutes to get the blood pumping.

And when it comes to maintaining stable energy levels, teachers, just like endurance athletes, need to be ever mindful of fuelling their efforts.

“They should take the opportunity to eat and drink throughout the day, particularly topping up on hydration,” he advises. “Breakfast matters but lunch is also important in keeping blood glucose levels stable. A lunch containing protein and slow-release carbohydrate should stop teachers becoming tired, lethargic and grumpy.”

But how practical, really, are these suggestions for teachers? The timetable is already packed, so it’s easy to see how an “exercise snack” could be pushed aside. And with many teachers required to arrive at school early, and lunchtimes often interrupted for meetings or duties, breakfast and lunch can also be minimal, or even forgotten altogether.

Emma Jones, headteacher at Withycombe Raleigh Church of England Primary School, in Devon, says that she’s tried to embed exercise throughout the school day in a sustainable way for her staff.

“Teachers are so constrained by time, they’re not good at self-care,” she says. “My role is to encourage staff to get off site at lunchtime and take a 10-minute walk. Having a break from the classroom makes a massive difference.”

Jones agrees. He says that, for optimal results, we need to exercise more often, not necessarily more intensely. “It’s what you can accrue over the day that really matters. It’s not a quick fix. Find an enjoyable activity that works for your lifestyle in the long term. Exercise during the day if you can. Taking a walk during lunchtime is ideal for recharging your batteries,” he adds.

And there are other methods schools can try. Joining in with The Daily Mile initiative is one option - this asks children to run or jog at their own pace for 15 minutes a day, outside with friends. Another option would be encouraging staff to sign up to the government-sponsored Cycle to Work scheme.

Leaders could also consider setting up mini sports leagues to add some healthy competition, and some schools even subsidise gym memberships. Whatever methods schools use to support staff to engage in more physical activity, the important thing is that the support is there in some form.

A marathon, not a sprint

Not only will this have physical and mental health benefits for individual teachers, but there could also be knock-on effects for the entire school community. A growing body of evidence suggests that exercise can have a transformative effect on overall organisational efficiency. Indeed, research shows that groups have an increased willingness to share and co-operate after synchronised physical exertion (Davies, Taylor and Cohen, 2015). So, running something like Zumba sessions for all staff may well be time and money well spent.

As the eminent neurologist Mark Tarnopolsky famously claimed, “If there were a drug that could do for human health everything that exercise can, it would likely be the most valuable pharmaceutical ever developed.”

Perhaps, then, when it comes to creating school environments that promote strong working relationships and better health and wellbeing, leaders should be investing in initiatives that promote physical activity and finding ways to free staff up to take part in exercise that helps them to get back to their evolutionary roots.

We’re used to following neuroscience to be stronger teachers, but in terms of being happier, healthier professionals, maybe it’s also time to learn the language of neurophysiology, if only to fully understand the messages our bodies and minds are constantly sending.

Sean Smith is a freelance writer

This article originally appeared in the 3 December 2021 issue under the headline “Tes focus on…Exercise for school staff”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article