Why school assemblies still have a place in modern education

Assemblies and schools go together. The school assembly is a permanent fixture, so much so that moving or cancelling it creates a day-muddling crinkle in the otherwise smooth running of the weekly timetable. It is part of the fabric of school life, as much a feature of the environment as the bell or playground scuffles. But what is it all about, really?

What purpose do assemblies serve and who really benefits (or suffers) from these regularly scheduled sessions? Once synonymous with religious observance, do assemblies still have a place in secular schools? In an increasingly crowded curriculum, can school leaders still justify herding students and teachers toward an assembly-shaped pit stop and away from the classroom? Or should we call time on assembly and consign it to the store cupboard to gather dust alongside the overhead projector and the Banda machine? Is holding a regular assembly a relic of a bygone era, outdated and unimportant given today’s school priorities?

With so many questions to answer, I did what all credible 21st-century writers do - I asked Twitter. I wanted to know what today’s educators thought were the best and worst things about assembly, and what highs and lows they remembered from their own school days.

What followed was less of a stroll down memory lane and more of a frogmarch. It seems that everyone has an opinion on assembly and everyone has a childhood memory that burns bright. Middle-of-the-road, indifferent reactions did not feature in the replies, which split respondents decisively into two camps. The EduTwitter community took me firmly by the virtual elbow and together we stepped back to look at assemblies from long ago.

In the 1950s and 1960s, assemblies took a decidedly rigid stance - literally for some students and teachers, who were expected to stand for the duration. Unsurprisingly perhaps, memories abounded of singing hymns, often directed by a kindly or terrifying minister, who was invariably remembered in great, looming detail.

Headteachers featured mainly as a menacing background presence, intent on keeping lines silent while the minister delivered his message. In general, as long as you were on time and kept quiet, you could reasonably expect to get through each assembly more or less unscathed - but woe betide the student who stepped out of line or who sneezed at an inopportune moment.

From the 1970s and 1980s, I heard tales of wonky heating systems and too-hot gym halls, exploding overhead projectors and first encounters with that most exotic of percussion instruments: the glockenspiel.

I also heard about lots and lots more hymn singing. More than one educator remembered a well-thumbed copy of the BBC’s Come and Praise hymnal propped up on the school piano (itself now an increasingly rare feature in modern school life). A staffroom straw poll revealed that most teachers of a certain age could recall many of the lyrics that lay between the book’s covers, with only a little prompting.

Enduring power

How can it be that so many of us have such vivid memories of school assemblies? How can we remember hymns from 30 years ago? Or the tilt of the headmaster’s brow as he scowled in our direction 50 years ago? What is it about assembly that has allowed it to bury deep into our long-term collective consciousness and snuggle in, while other events and experiences have slipped away?

Perhaps the answer lies in the enduring power of the individual to amaze, inspire or terrify. Moments of crushing humiliation or soaring pride take root inside and shape who we are and who we will become. And of all the myriad assembly memories, two things seem to have remained constant across the decades: numb bottoms and solo performances.

The assemblies of the past were generally characterised by one individual who was firmly centre stage, running the show, able to impress the power of his or her personality on a captive audience of young people. The well-worn groove of memory, furrowed over and over by weekly routine, ensured that this individual and the assembly experience itself became a fixture in the mind, a permanent reminder of the person and the feeling. So much so that those assembly memories became a touchstone for our school days, a mental shortcut to the way we remember our educational experience.

Zooming out from anecdotes about taking a thrown hymnbook to the side of the head if you were caught talking or vicars eating daffodils in the name of elucidating a Bible parable, we can begin to discern the overarching feelings that these individual experiences inspired. In broad terms, they can be simplified into two categories: on one side, deep discomfort, trauma and humiliation; and on the other, a powerful feeling of warmth and belonging - of being part of something important and special.

Returning to the present day, I wonder how many educators and school leaders carry these polarised feelings and memories into our classrooms, and how this shapes the assembly experience they provide for their own students.

Certainly, those who speak warmly of assembly, then and now, point to engaging storytellers and happy singing. They recount experiences that brought people together, united by a shared goal, interest or belief. School leaders who remember assembly with a shudder describe quite the opposite and how it instilled in them a quiet determination to do things differently.

Religious observance has been decisively dropped from the assembly must-have list in the past decade, but what are the vital ingredients that have come along to replace it? Celebrating success must surely feature prominently. Dedicating time to highlighting the achievements of students through a flurry of stickers, certificates and warm praise has become the cornerstone of assemblies across the land, illustrating how culture and ethos have shifted over time.

School leaders who share the stage and step back from running a one-man show also highlight a cultural shift away from the totalitarian regimes of the past, where the headteacher’s word was final. By encouraging students to take the stage, share their talents and opinions, and present their learning to proud parents and carers, we can reposition assembly. No longer a passive “done to” experience, it becomes a space to showcase the work of the school and celebrate the skills and knowledge of young people.

The third significant element shaping the assembly experience today is the weekly opportunity to do some brand development. As one school leader on social media put it: “Assembly is where you consciously build your school ethos.”

Gathering the whole school together in one place, at one time, used to be about collective worship. Nowadays, it is more likely to be about getting everyone to sing from a very different kind of hymn sheet. Using assembly to put the school’s vision, values and aims front and centre for students and staff provides weekly affirmation that we are all in this together - that we are working towards a shared purpose. There can be few loftier ambitions for assembly than for it to strengthen the bonds that hold the school community together.

Skilled school leaders use assembly time to model the actions and reactions they seek to elicit from their students and staff. They plan assemblies that prick the conscience or inspire pride, sympathy or even righteous indignation and then model responses to these feelings that fit with the school’s ethos.

In short, they use assembly to show how to do it “our school’s way”. The ripples of a good assembly can be felt in the school all week. From crisp packets disappearing from the playing field to a sharp increase in doors being held open for passing visitors, getting the message across in an inclusive way about how things are done around here has a powerful impact.

Commitment to shared goals

So, perhaps schools ought to keep assemblies around after all, and continue to protect them when the timetable begins to press in from all sides. Coming together to celebrate success, showcase learning or strengthen commitment to shared goals is time invested in making the school a special place to be. The weekly assembly is an opportunity for school communities to both keep house and reaffirm the ties that bind: it ensures we stay connected.

Across the decades, good assemblies have generated a feeling of warm belonging, of being part of something that matters. Like almost everything else in education, there is no one right way of doing assembly. So much depends on context and priority, the nuances of relationships within the school community and all the subtle shades of communication that lie therein. What works in one school may not work in another. But the core ingredients are there for the taking.

School leaders can choose from a veritable smorgasbord of options: from catchy songs and words on a screen to get the feelgood factor and sprightly student-led performances to applause-laden celebrations of success and lead-from-the-front inspirational speeches.

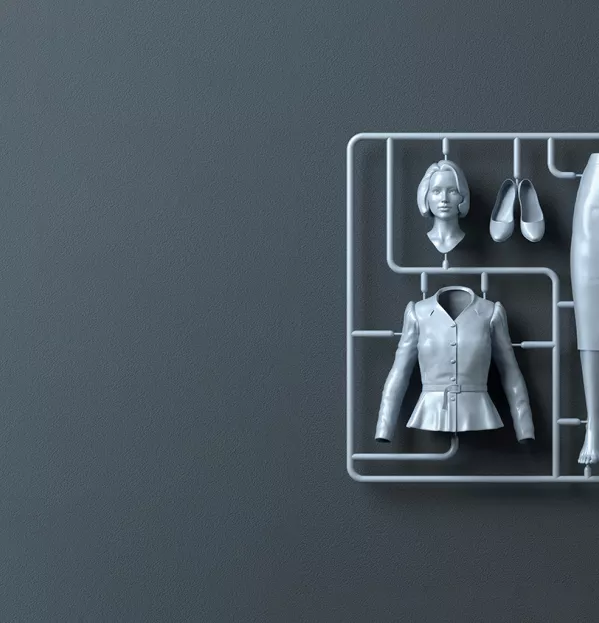

The choices stack up like enough Nordic flat-pack furniture to fill a store cupboard, just waiting for the right person to come along and put them all together. Whatever school leaders decide to build, if they want a school to be proud then one thing is certain: some form of assembly is definitely required.

Susan Ward is depute headteacher at Kingsland Primary School in Peebles, in the Scottish Borders. She tweets @susanward30

This article originally appeared in the 7 February 2020 issue under the headline “Instructions for assembly: build something together”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.