Why teachers’ first impressions really do count

Think back to your school days. Do you remember how it felt to meet a new teacher for the first time? They may not have said anything. They may not have done anything. But the silent, complex process of judgement was immediately in progress.

Their clothes, their posture, their mannerisms - all minutely analysed for signs of the sort of teacher they would turn out to be.

And the first time a new class sees you, they are doing the same.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But it can be. Because, unfortunately, there is a lot of truth in the saying that first impressions last.

The process happens automatically and extremely quickly: within split seconds, according to Irmak Olcaysoy Okten, a post-doctoral researcher of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Delaware, who has undertaken a number of studies into the subject.

“Even when they have no background information about a person, people very easily go beyond the information at hand and form general impressions about others’ characteristics,” she explains.

“Research shows that this happens within milliseconds. They infer traits from simple behaviours - even faces - by assuming that what they have inferred is a stable, essential characteristic of the person.

“Having watched someone driving instead of walking one block, for example, people tend to spontaneously infer that the person is lazy,” she continues.

“They will then expect this person to be lazy in the future in a completely different environment, unless this person has a clear, observable reason for engaging in that kind of behaviour.”

The thing is, these first impressions are often proved to be accurate. It seems that human beings are pretty good at assessing other people through snap judgements.

Sizing up

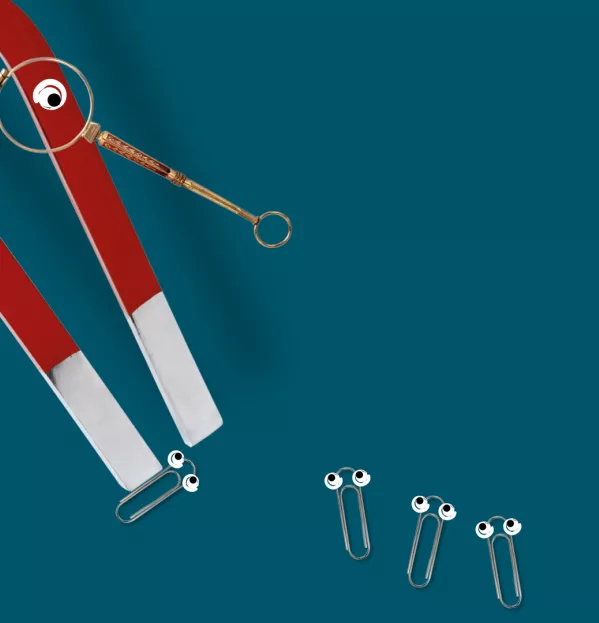

Olivia Fox Cabane is author of The Charisma Myth: how anyone can master the art and science of personal magnetism, where she cites research conducted by a team from Harvard University. Researchers showed students a two-second video clip of a teacher they had never encountered before and then asked them to evaluate the effectiveness of the teacher. The clip didn’t include audio (bit.ly/TeacherClip).

“The researchers then compared these evaluations with those of students who’d experienced the same teacher for a full semester,” Fox Cabane says. “Both sets of evaluations were impressively similar. This suggests that without hearing a word from the teacher, or attending one class, complete strangers could predict with fair accuracy the ratings this teacher would receive.”

What happens when we see someone for the first time is a complex process of data assimilation, explains Alexander Todorov, a professor at the department of psychology at Princeton University and author of Face Value: the irresistible influence of first impressions.

He explains that when we encounter a person for the first time, we automatically start to observe all available visual cues - including emotional expressions, body gestures, attire and grooming - and integrate them into our impression of them.

“We are also paying attention to auditory cues,” says Todorov. “Which cues will prevail depends on the context. For example, we have shown that for extreme emotions, the face conveys very little information, but the body gestures are very informative.

“When there is an absence of a specific goal [in the encounter], we typically try to infer whether the intentions of the person are good or bad and whether they are capable of acting on them.

“But when we have a specific goal in mind, such as hiring, we try to infer the attributes that help us achieve our goal, in this case the competence of the person.”

So your students are likely sizing you up for how strict you might be, or how friendly, while you may be assessing them to try and spot the troublemakers.

In fact, this type of judgement is by far the most common. Research has found that around 80 per cent of our judgements of others essentially boil down to assessing them on two traits: trustworthiness and competence (bit.ly/TrustComp).

“It’s been argued that it’s evolutionarily advantageous to first judge whether a person is trustworthy - a friend or foe, with good intent or ill - and then to assess their ability to effectively act on those intentions,” explains Vivian Zayas, associate professor in the department of psychology at Cornell University.

And then between adults, there’s the added issue of attractiveness, adds Clare Sutherland, a research fellow at the University of Western Australia’s School of Psychological Science.

“We think that people are assessing adult faces for threat and also for partner and ally selection,” she says. “These judgements would have been important for survival in our evolutionary past, even if they don’t always seem useful in the modern world.

“Having said that, new research from our lab [bit.ly/SutherlandFaces] suggests that impressions of children’s faces may be a bit different. Adults still care about how nice children look, but also how shy they look, which is a bit different from perceptions of other adults.

“It could be that people are trying to judge social competencies instead, and the difference might relate to the different social goals we have with children and adults.”

Research undertaken by Zayas and Gül Günaydın, assistant professor in the department of psychology at Bilkent University, found that people can form impressions of others based on a photograph and these judgements will colour how they end up behaving towards that person when they meet face to face (bit.ly/ZayasGunaydin).

“The one [person] who thought that the [other] person was conscientious is likely to walk away from a face-to-face interaction believing the initial impression,” says Zayas.

“Likewise, the person who thought that the person in the photograph was not conscientious and more impulsive is likely to walk away from a face-to-face interaction believing that initial impression.”

Interestingly, two people can look at the same photograph of the same person and come away with very different impressions. That’s because impressions are very individualistic, Todorov explains.

“If you think of the different contributions to impressions, in the case of attractiveness [the most appearance-based impression] about half of these contributions are shared: we agree on them,” he says.

“The other half are individualistic. So it is perfectly possible - in fact, very likely - that two people might have opposite impressions. Individualistic impressions originate in one’s culture and one’s experience with familiar people.”

Sutherland is currently working on an Australian Research Council-funded fellowship aiming to understand the scope of individual differences in first impressions, how these differences are coded in the brain, and whether life experience or genetic differences are driving individual perceptions.

“At the moment, the answer seems that impressions are equally shared and individualistic,” she says. “People certainly agree on their impressions, which explains why these impressions ‘count’ for so much in the real world, but at the same time, there is a strong individual component to impressions, too.”

So with 30 children in front of you, therefore, trying to appear a certain way seems futile.

And so that makes any blanket advice on how to start off with a new class - like the old “don’t smile until Christmas” - similarly unhelpful. The impression that each of those children will get may not be the one you are trying (or told) to give.

Test of time

So what if you don’t get off on the right foot? How long might that first impression last? It will certainly influence interactions immediately afterwards, but will it endure even in the face of contrasting data?

Sutherland has undertaken research exploring how strong first impressions really are and whether or not they can be overridden over time.

“It turns out that while people learn to base their trust on the person’s actual behaviour, the effect of the first impression doesn’t go away by the end of our experiments so far,” she says. “People who look untrustworthy seem to be at a particular disadvantage, because our participants didn’t seem to ever really, truly trust them.”

In Zayas’ work with Günaydın, researchers found that impressions based on a photograph influenced interpersonal face-to-face interactions between individuals as much as six months later - but this may be a result of self-fulfilling prophecy.

“When someone likes another person based on the photograph, their non-verbal body language in a face-to-face interaction expresses warmth, engagement and interest,” says Zayas.

“This in turn elicits a positive response from their interaction partner. And the positive response confirms the initial first impression. This is not to say that first impressions cannot be changed. But to change them, a person needs to encounter very clear and unequivocal evidence that clearly signals a different impression.”

Okten’s research into this subject shows the resistance to change an impression of someone is especially strong for implicit impressions; those that are formed spontaneously, with limited intention and awareness (bit.ly/Okten2019).

She references a recent experiment in which individuals were presented with a simple piece of information about a person - that a man shouted at a child today, for example - and formed impressions based upon it.

They were later given information that completely changed the meaning - that the kid was approaching a hot oven, so the person was not being mean, but protective - yet found that the initial judgement was hard to shift.

“We observed that the impressions they formed from these simple behaviours stuck,” she says.

“In other words, when a person is initially construed as mean, receiving another piece of information about that person, which challenges the initial impression, may not be enough to completely overturn the implicit impression.”

However, she adds that some research studies (such as Cone and Ferguson, 2015, bit.ly/ConeFerguson) have suggested implicit impressions can be “updated” under some conditions.

“When individuals learn expectancy-incongruent information about the person that is extreme (such as donating a kidney to a stranger) or they accumulate that kind of information over time”.

Todorov agrees with Okten that although it may be tricky, it’s not completely impossible to overcome a bad first impression.

“First impressions form very rapidly, but we can change them if we have good evidence to the contrary,” he says.

“A student might dislike a teacher at first, but if the teacher is inspiring and able to convey the material in a way that the student understands, the student will change their impression accordingly. The key is whether we have opportunities to obtain diagnostic information about the actual attributes of the person.”

So a bad first impression is not terminal. But rather than try to correct how your pupils perceive you, the best approach is - obviously - to make a positive impression from the outset.

Turn up the heat

For Alan McLean, a psychologist, author and former teacher, the key to this is for teachers to make sure they come across as warm and competent.

“The most important thing to bear in mind for teachers is that if we spot one single competent behaviour from another person, we assume they are capable,” says McLean. “We think that person looks smart, they’re a good teacher and they know what they’re talking about.

“But if a person displays one single example of cold behaviour towards us then we stereotype them as hostile. It just takes one cold behaviour and the student won’t like them.

“So the key message for teachers is to come across quickly and early on as competent and essentially warm. I know a lot of teachers don’t want to be seen as warm because they think they’ll be seen as being soft, but if kids don’t like you from the start, it’s hard to change that.”

Likewise, if teachers make snap judgements of pupils, they need to be aware that the above processes are in play and that their view may well be flawed.

You may think this all makes that first day of the year even more complicated than you thought it was already, but here’s the thing: this is not about changing who you are, it is about putting the relationship-building process with your class on the same level as your lesson planning.

It is about being the best version of you, not just the teaching you. It is about being yourself and being aware that all this goes on. And that is something which, ultimately, should not be frightening - it should be empowering.

Simon Creasey is a freelance journalist

This article originally appeared in the 23 August 2019 issue under the headline “Why first impressions really do count”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters