- Home

- Leadership

- Strategy

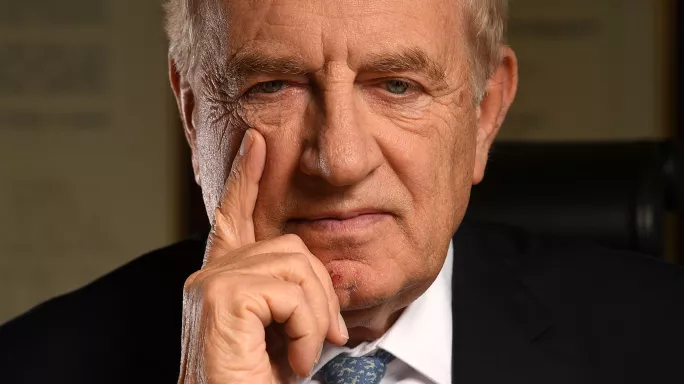

- 10 questions with... Sir Peter Lampl

10 questions with... Sir Peter Lampl

Sir Peter Lampl OBE is a British philanthropist who, in 1997, founded The Sutton Trust with the aim of improving social mobility and access to higher education for disadvantaged children.

Under Sir Peter’s leadership, The Sutton Trust has funded over 250 research studies and initiatives, and these take the form of various programmes such as summer schools, work in the early years and giving young people access to work experience.

In 2011, The Sutton Trust founded the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), and with Sir Peter as chair, it works to improve the performance of the poorest children in the worst-performing schools.

He spoke to Tes about his experiences as a student with Oxford aspirations, the reasons why he moved from business to philanthropy, and the crucial changes that the education system needs to make to achieve social mobility.

1. Who was your most memorable teacher and why?

When I was 17, I moved from Reigate Grammar School to Cheltenham. This was when I was halfway through sixth form and, as you can imagine, I was scrambling a bit.

The change was tough as I was moving from one school to another where, although I kept the same subjects, the two schools had been using different exam boards, two different syllabuses and were completing the units in different orders - this was really hard going and I was floundering.

Then my luck changed when my new chemistry teacher at Cheltenham invited me for private tuition - and, of course, this was hugely effective. The help he gave me was priceless.

His name was Mr Thomas, but his nickname was Claude. Because of the help he gave me during our one-on-one tuition, I got an A in chemistry. Thanks to his guidance I did the Oxford entrance exam, and because of him, I got to Oxford to study chemistry, specialising in physical chemistry.

2. Have you ever spoken to your memorable teacher since you left school?

I never got a chance to speak to him, he was already elderly when I was at school and he had passed away when I eventually came back to visit the school.

I missed him for a while, so I went to my old school and set up an annual award in his honour that gives a disadvantaged child who has been identified as having academic potential a fund to provide financial support.

3. What funny memories do you have from school?

I had a physics teacher who couldn’t stand me. He heard I was studying for the Oxford entrance exam and would say to me again and again: “The only way you’re going to Oxford is on the bus.”

But because of Mr Thomas, I did end up going to Oxford - and not just on the bus. Years later, after I finished my undergraduate degree, I was awarded an honorary degree and had a building named after me.

He would have had a fit if he had known what I achieved. The truth is, people can surprise you if you give them a chance.

4. What sort of student were you?

When I moved from Wakefield to Reigate when I was 11, I wasn’t very popular - mainly because of my broad Yorkshire accent. One day that changed, when I was on my way to school I spotted an advert for the Beatles Christmas Show at Finsbury Park.

I saw an opportunity. I bought 16 tickets, kept a few tickets back for my friends and sold the others. And that’s what made me popular! Selling the Beatles tickets.

What’s funny is that when we actually went to the show, you couldn’t hear a thing because of all the screaming. If someone had asked me what they played I would have no idea.

5. What made you choose to work in education?

I came back from the US, having been there 20 years working in business, and I sensed things had changed a bit.

For example, when I was at Reigate Grammar School it had been 100 per cent free, and when I returned I found it had become 100 per cent fee paying. I realised under the new regime that I wouldn’t have been able to go to the school, and neither would my friends - and I was shocked.

I was invited to lunch by the president of my college at Oxford, and I was a popular guest at dinners and things like that, and I had lunch with Keith Thomas [then president of Corpus Christi College at Oxford].

I asked him how we could improve representation of children from disadvantaged backgrounds. He said they don’t apply, or if they do apply they tend to not be given a place.

So then I went to the people who worked with admissions to Oxford University, and I said to them that this is a problem.

My solution for this was a summer school, and when I offered to pay for it, they agreed that we could start one up.

That was how the first of our now famous summer schools began. Of those children who attended the first one, 60 were later awarded places at Oxford. This is what got me started.

Today we have 13 universities involved, 11,000 children in summer schools and other programmes, and have impacted government policy on more than 30 occasions.

6. Have you had difficult times in your career?

There was a very difficult time for me when I became very depressed. It was horrific, and I became so depressed that I couldn’t work, and I actually disappeared for two days and people thought I was probably dead.

That was the most difficult time, and that deep depression is a terrible thing, but I worked my way through it.

Happily, I’ve not been depressed for a long time now. But when it hits, it’s awful.

7. In your dream school staffroom, who would be your colleagues?

I would want David Blunkett in my staffroom - I worked with David a lot. When we did the summer school for Oxford, I was invited to meet David. I was expecting it to be just the two of us…but when I arrived the room was full of people! A whole football team worth of staff. And then I realised that this was how it works in politics - everyone shows up.

David’s a remarkable man to have done what he’s done. He’s very bright and he did a wonderful job as education secretary.

The other person I would like in my staffroom is David Levin, who was head of the City of London School. We worked together with private day schools and, with his contacts, he put together over 80 independent schools that signed up to say they would go for open access. He is a delightful guy who I would want in the staffroom.

8. What concerns you about the current school system?

People talk about a “comprehensive system” and we don’t have one.

In our current system, we have so many opt outs - we have boarding schools, which make up 1 per cent. Then you have independent day schools, that’s another 6 per cent. Then you have grammar schools, that’s 5 per cent. Then you have faith schools, that’s 2 per cent. And then you have comprehensives in affluent areas where the house prices are high.

Realistically, you are looking at over 20 per cent of schools in this country that are not comprehensive. They are populated by rich people. Whereas somewhere like Germany has a truly comprehensive system where all people go to a state school. We don’t here, and it’s a huge issue.

The best thing to do - if I could wave a magic wand - would be to implement a completely comprehensive system. That is my biggest beef.

I also think one of the worst aspects of our system is that we have constant change at the Department of Education with new education secretaries. You would never run a business like this on a 17- to 18-month tenure - no one can keep up with it.

9. If you became education secretary, what would you change?

If I were in charge, I would look to raise the performance of the 465,500 teachers we have. That is the most fundamental way to improve the education system in this country.

I’ve been chairing the EEF and we know what works in schools. If you have a teacher in the bottom 10 per cent versus the top 10 per cent and compare them, the difference in outcomes is astronomic. Over a million pounds of difference.

I would like to see us improve teacher performance. CPD is where it’s at and we should be doing better and more of that. Currently, a lot of what is on offer amounts to little more than box ticking when it needs to be serious and fundamental.

10. What will schools look like in 30 years?

I would like to see a breakdown in social selection in the education system.

To do that, I believe we need to do more about opening up private schools. They won’t be abolished so we’ve got to live with them, and therefore the only option is to open them up.

Similarly, grammar schools are socially selective with just 2 per cent of pupils eligible for free school meals. We have to do something with the grammar schools, as like private schools, they’re here to stay. Also, like independent schools, they’re good schools - so you don’t want to destroy them.

Instead, you have to do outreach. I think they should have to give twelve hours of tuition to disadvantaged children who wish to apply, and that way they would have more of a fair chance.

Another way we could break down social selection is where you have comprehensives in high house price areas, you limit admissions from the area. To do this, you halve the places so that 50 per cent are children who live around the school, and the other 50 per cent are balloted places.

I think it is of the utmost importance that we take more action on social selection. I don’t know of any other advanced country that has what we have: we have boarding schools, private day schools, grammar schools, and comprehensives in rich areas.

It’s skewed against the average and below-average family, so something needs to be done.

Sir Peter Lampl was speaking to senior analyst Grainne Hallahan

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles