Is this MFL’s ‘moment’ or will reforms hasten its decline?

Language learning in schools has been hit by a series of threats in recent years, including teacher shortages, missed targets for those studying the English Baccalaureate (and thus languages), Brexit, harsh grading and a packed curriculum.

Subject experts hope Labour’s decision to undertake a curriculum and assessment review will provide a “moment” to raise the status of modern foreign languages (MFL) as part of a broad education.

However, there are also concerns that the next set of education reforms could diminish the subject’s position, making a challenging situation even worse.

Experts warn that if the EBacc’s importance as a performance measure is lessened, and with radical changes to Ofsted on the way, incentives for schools to focus on MFL will fade.

Risks to languages if EBacc scrapped

There has been growing criticism of the EBacc, which recognises the achievement of pupils who achieve good GCSE grades in English, maths, sciences, a humanity and an MFL.

Labour’s manifesto only made passing reference to the EBacc and did not mention languages at all, but it did voice concern that creative and vocational subjects are “too often being squeezed out”.

Some organisations have called for the EBacc to be reformed or scrapped altogether, including the left-wing IPPR think tank, which has strong links to Labour.

Although the take-up of languages at GCSE has remained stubbornly low, the EBacc measure was nonetheless a clear indication that studying a language was considered important.

Bernadette Holmes, director of the National Consortium for Languages Education, says that if the EBacc disappears, “certainly, that would weaken the position of languages in the curriculum...heads would say, ‘Ah well, I now have the flexibility not to do that’”.

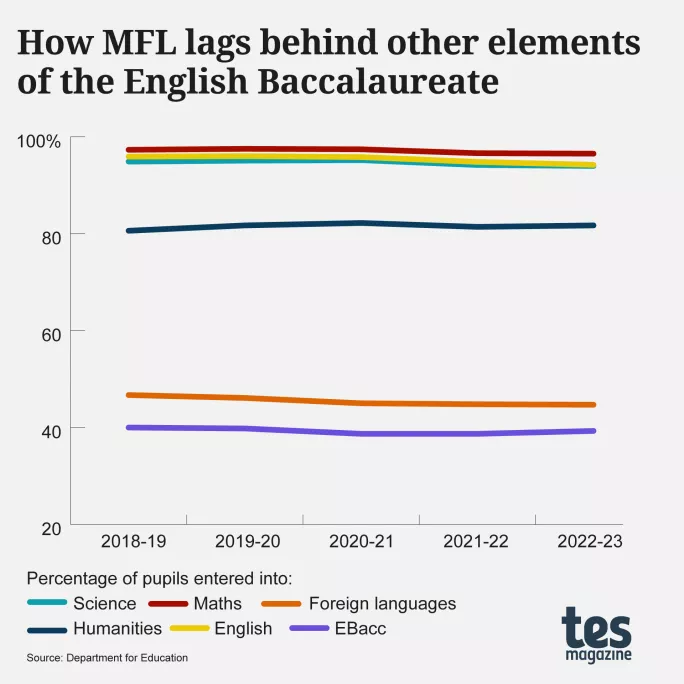

Any reduction in take-up would be from an already low bar. Former schools minister Nick Gibb wanted 75 per cent of students doing EBacc subjects by 2022 and 90 per cent by 2025.

But the most recent data for 2022-23 shows that EBacc take-up was 39.3 per cent - dragged down mainly by low numbers for MFL.

Outside of the three compulsory EBacc subjects, 81.7 per cent of students studied history or geography, compared with only 44.7 per cent taking an MFL.

Still, David Blow, of the Association for Language Learning, says Gibb’s emphasis on the EBacc - and its inclusion in Ofsted’s 2019 Education Inspection Framework - have both supported the study of MFL.

Ofsted less focused on individual subjects

The inspection framework put an increased emphasis on curriculum breadth, with inspectors carrying our deep dives into individual subject areas. The watchdog also developed a curriculum unit, recruiting subject expert HMIs to lead on research, reviews and training.

When Ofsted told schools they needed to do more to ensure the curriculum was “ambitious” for all students, the “subtext” was that they should increase EBacc numbers, Blow says. This, in turn, meant a “need to increase the numbers doing a modern language at key stage 4”.

But Ofsted is now working on a new inspection framework, and deep dives have already been removed from ungraded inspections. As Tes revealed earlier this year, its curriculum unit has been “completely scrapped”, with subject leads mostly working on routine inspection.

These changes are fuelling concerns that the accountability system led by the Department for Education and Ofsted will not be promoting MFL in the way it has in the past.

“We don’t want to see the EBacc losing importance, or a new Ofsted framework with less emphasis on curriculum breadth and specific subjects, as this might make the issue [ie, the challenges facing MFL] worse,” Blow says.

- Data: GCSE 2024 results by subject

- Comment: How we doubled MFL uptake in three years

- Related: Parents’ influence key in MFL take up

Teacher shortages in MFL subjects

A potential reason behind the low take-up of languages at GCSE is the lack of specialist teachers.

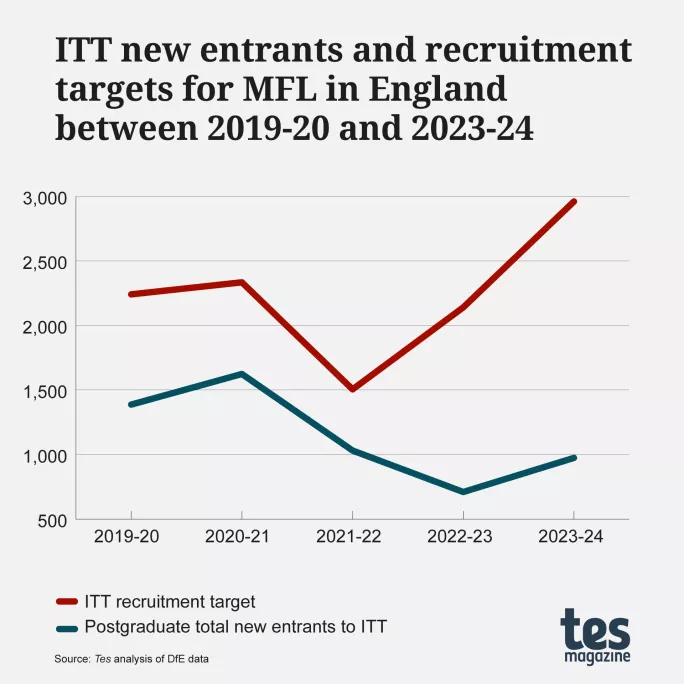

Targets for recruiting MFL trainees have been missed in each of the past 11 years and Jack Worth, education economist for the National Foundation for Educational Research, expects it to be missed in 2024-25 as well.

In 2023-24, only a third of the target number of recruits started courses - 974 of a target of 2,960. MFL has been among the subjects with the largest shortfalls in the past two years.

And the British Council’s 2024 language trends survey found that six in 10 schools, both state and private, said recruiting MFL teachers was a challenge.

‘Severe’ grading in MFL assessment

Blow says one of the driving factors in both the lower take-up of MFL and the shortage of teachers is that these subjects have been graded more harshly than others in the past.

In 2019, Ofqual acknowledged that French and German had been “severely graded in comparison to other subjects”.

Its plans to change this were interrupted by pandemic grading, but Ofqual required exam boards to award languages more generously at grades 9, 7 and 4 in the summer of 2023.

This summer, exam boards were required to make positive adjustments at grades 9, 7 and 4 for GCSE German, and grades 7 and 4 for GCSE French.

Blow says the “severe grading in GCSE modern languages” is “a historical anomaly” that affects students - who mistakenly believe they are less good at languages than other subjects - as well as teachers facing pressure to improve results.

As GCSE numbers see a “dramatic decline”, the available pool of UK modern language graduates to train as teachers is also shrinking, he points out.

Vicky Gough, the British Council’s schools adviser, warns that this situation is compounded by the patchy availability of university courses offering language degrees, according to research.

Brexit complications

Subject leads warn that Brexit has hit pupil engagement and teacher recruitment in MFL, too.

Katrin Sredzki-Seamer, director of the National Modern Languages SCITT in Sheffield, says: “In the past we always had graduates from Spain, France and Germany coming to train and then staying.”

Now, EU citizens require visas and SCITTs, unlike universities, are not able to sponsor them.

Even if EU candidates can get a visa, they now face international fees, which makes coming to train in the UK as a language teacher less appealing, Sredzki-Seamer says.

“This gateway is going to get smaller and smaller,” she warns.

Fewer overseas school trips since Covid

Experts say there has also been an impact on school trips.

Blow warns: “Lockdown and the pandemic stopped exchanges and visits, but the practical consequences of Brexit around passports and getting visas in both directions has been a great inhibitor on reactivating them.”

School Travel Forum, an association for UK companies offering educational visits, said there were 9,830 overseas school visits from the UK in 2019, and 6,908 in 2023 - a 29.7 per cent fall.

Gough highlights how, in 2018, 11 per cent of secondary schools had no international connections or partnerships with schools abroad: this has shot up to 36 per cent.

“I do think that those things - having a connection, making a visit, being open to other cultures - are really important, and not having those things, I think probably does make a difference to the appeal of languages,” she says.

This is echoed by Stuart Burns, CEO of the 36-school David Ross Education Trust and a former MFL teacher, who says more cultural, sporting and adventure trips abroad to France, Spain and Germany “could help improve popularity”.

He says the government could consider subsidising one trip per child during key stage 3, and, if unaffordable, finance “should still be extended to supporting disadvantaged students to experience a trip abroad”.

Sarah Hau, who works as head of MFL in a school in London, says that the cost of trips for families, added to teacher workload, are making visits and exchanges more challenging for some schools to run.

However, she believes they are crucial in engaging students. “I have just got back from five days in Paris with Year 11s and we were able to give them a completely immersive experience,” she says.

“It’s so important as part of the appeal for choosing a language because they know there is a trip to look forward to, and it allows them to use what they have learned in the classroom and see the purpose and benefit of it.”

Tim Crapper, an MFL teacher from Buckinghamshire who retired this year, says extra “bureaucracy” now makes Dover crossings longer and more “tiresome”, but insists they are worth it.

“Exchange visits are vitally important: they bring the country and the language the pupils are learning to life - and yet I know the numbers doing them are falling,” he says.

Jury out on curriculum reforms

Headteachers of both private and state schools also point to the importance of making the curriculum as relevant and engaging as possible.

Crapper questions whether recent changes to GCSE French, such as assessing students on the most common vocabulary, would support this.

These changes “could make the subject more accessible as the content being covered is thinner”, he says, “but there is also an increased emphasis on grammar...the impact is yet to be seen and reviewed”.

Katherine Vintiner, principal at Hampton Court House, an all-through independent school, says the previous curriculum “focused on a narrow range of topics, often lacking a cultural dimension that might otherwise engage students”.

While the latest reforms aim to make the content more relevant, “we will have to wait to see how impactful these changes will be in practice”, she says.

Thornhill Academy, in Sunderland, almost tripled the uptake of MFL subjects at GCSE last year. This came after the school educated pupils about the benefits of developing linguistic skills and the employment opportunities in the area - such as with the video games firm Ubisoft, which has a base in the North East, says deputy headteacher Liam Clark.

The school has also increased the amount of time spent on the MFL curriculum in Year 9.

MFL is ‘time poor’, particularly at primary

However, experts warn that, at present, language subjects are “time poor” and in primary schools, this time is particularly vulnerable.

Holmes says: “It may be allocated half an hour a week, but that half an hour is even vulnerable for a variety of reasons, as it doesn’t have the priority status it should have within the primary curriculum. It doesn’t give us a strong foundation. We need to have longer.”

Since 2014, it has been a statutory requirement for primary schools to teach a modern or ancient language to pupils from age 7, but a research report by Ofsted warned that quality of provision at key stage 2 is variable, with “staff expertise, curriculum planning, time allocation and transition all cited as barriers”.

Many experts and classroom teachers point to language learning in primary school as being key to improving MFL take-up in secondary and beyond.

A main obstacle is the capacity of the workforce. Hau did her GCSEs in 2004 - the last year in which MFL was compulsory - and she warns that improving the teaching of MFL in primaries will become increasingly challenging as there are now generations of primary school teachers who have not studied a language beyond Year 9.

Sredzki-Seamer suggests that more subject-specific support should be made available to primary teachers and that a qualified primary MFL specialist PGCE could be created to promote high-quality teaching of the subjects to younger pupils.

‘This is the moment’ for MFL

Subject experts are convinced that MFL should not only be central to the school curriculum, but also be seen as an essential skill in a young person’s personal development.

Now they want to ensure their arguments can turn the tide.

Holmes tells Tes: “This is the moment to do this because we have the curriculum and assessment review...this is the opportunity now to reshape, rethink and reconceptualise how we work in languages.”

Failing to do so, she believes, will not only damage the education system but the life chances of disadvantaged pupils.

“If we don’t have a change in attitudes towards languages, you will have schools that will fossilise in terms of what their curriculum offers,” she says.

“It will not be a curriculum for the future - it becomes very much a curriculum that is isolating and reductive. And it will be immensely divisive for those children who have no access to any other cultural input if they are not able to study a language in the future.”

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article