- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

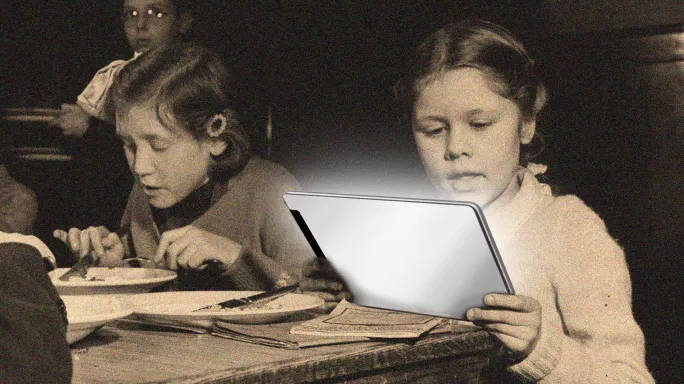

- Do phones, tablets and laptops really disrupt learning?

Do phones, tablets and laptops really disrupt learning?

This article was originally published on 24 January 2024

Sweden’s school minister Lotta Edholm recently made headlines when she announced that, after years of leading the charge as the world’s “most vibrant digital ecosystem”, the country was pulling back on digital technology in the classroom. Beginning this year, its students were going to spend more time with printed books, paper and pencils instead of keyboards and screens, the minister said.

Swedish schools are doing a digital 180, reversing key decisions such as making digital devices mandatory in preschool and early elementary school. The reason cited is a decline in students’ skills. “Sweden’s students need more textbooks,” Edholm said in March. “Physical books are important for student learning.”

The decision was made months before the Programme of International Student Assessment (Pisa) announcement of a decline in reading and math scores across the globe. After test scores were released, experts and journalists speculated that the precipitous drop in scores stretching back a decade was somehow connected not only to the pandemic but to the now ubiquitous use of laptops, tablets and phones in classrooms.

There are “multiple signs that students aren’t learning as well when they are surrounded by screens”, wrote US education reporter Jill Barshay on X (formerly Twitter), commenting on a recent spate of research pointing to how overuse of digital technology correlates with learning decline.

There’s a growing tech-for-learning scepticism in schools, too, that includes, but is not limited to, fears around declining academic performance. The Department for Education issued guidance in October suggesting a ban on all smartphone usage during the school day, including breaks, following other countries that have already issued classroom phone bans, such as France, Italy and Portugal.

While no national guidance has been issued in the US, American schools are also cracking down on phone usage - even though 98 per cent of US students use laptops connected to the internet (most purchased with Covid relief money) for daily lessons.

Growing evidence links constant digital tech usage, in and out of school, to declining mental health among young people, something both the US surgeon general Vivek Murthy and the UK children’s commissioner Dame Rachel de Souza have named a “crisis”.

Laptops, iPads and phones played a crucial role during distance pandemic learning, yet the academic and social fallout on the return to “normal” after the pandemic years has schools wondering whether they should plough ahead with the edtech revolution or exercise more caution with digital tools.

However, the more you dig into the issue, the less it becomes about tech as a whole and the more it seems to be about which tech, when it is used and how.

Decline in attention and attainment

Schools have been using different forms of digital technology, from tablets to laptops to interactive whiteboards, for well over a decade. But the pandemic made digital learning nearly universal. By 2022, surveys showed, almost all US K-12 (Years 1-13) students used a laptop for at least part of the school day, and the same is true in the UK.

Moreover, a 2022 SMART Technologies report showed that 64 per cent of UK classrooms “embed technology in everyday teaching and learning practices”.

What has the impact been on education? While the pandemic might be partly responsible for the global average performance in maths falling by 15 points, and reading by 10, in the past couple of years, experts suspect it’s not the only reason.

“Performance in reading and science began to decline well before the pandemic,” the Pisa authors write. “This indicates that longer-term issues are also at play.”

Pandemic school closures, they estimate, only account for about 10 per cent of score decline. But there is another correlation that we should take note of: according to research, peak academic performance and student mental health both began to decline right around the same time, about 2012, when the majority of students acquired a smartphone.

And while there are those who would question how far international tests like Pisa accurately reflect the full picture of student attainment, it’s worth noting that students themselves have reported that technology is having a negative effect on their learning.

In a first-time survey on digital distraction, 2022 Pisa student respondents said that phones and laptops were interfering with their school work, with 65 per cent of 15-year-olds reporting that they were distracted by their digital device during maths lessons and 45 per cent saying they felt anxious without their phones near them. Students who reported being distracted by others’ digital device use in class “scored 15 points lower than students who reported that this never or almost never happens”.

Reading comprehension is also affected by an overuse of digital tech, some suggest. While studies confirm that the average person reads more actual words than ever - mostly owing to social media and texting - the vast majority of that reading is “skimming”.

Some cognitive scientists, such as Maryanne Wolf, have argued that the comprehension that comes from deep reading - being completely immersed in a book - suffers as a result. A growing body of evidence points to greater student comprehension when reading from paper books than from tablets or laptops, including a soon-to-be-published study from neuroscientists at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

Studies on how digital device usage affects student attention are murkier. Some indicate that the buzzing and beeping smartphone notifications affect student attention even if the student only has the phone in their pocket. Yet cognitive scientists like Daniel Willingham, in his book The Reading Mind, say the picture on attention is more complicated - it’s not so much that kids’ brains have changed but that video games and social media have altered student expectations of what is worthy of their attention.

“The consequence of long-term experience with digital technologies is not an inability to sustain attention,” he writes. “It’s impatience with boredom.”

Yet teachers - especially, it seems, US teachers - say they observe how constant digital connectivity has changed students’ ability to focus.

“I see a difference now in kids,” says Gabe Hart, a veteran US high school English teacher from Jackson, Tennessee. “What I’ve seen is kids’ attention span has gotten a lot smaller. They get their information in bites rather than the ‘whole meal’. Their stamina is a lot lower now than when I first started teaching.”

Scott Symons, a high school history teacher in upstate New York, puts it more bluntly: “They have lost skills and we are seeing it. Students are so good at texting short sentences but they can’t get bigger ideas across.”

Christian Bokhove, professor of mathematics at the University of Southampton, says he hasn’t seen quite that level of skill and attention depletion among UK students, maybe owing to an overall more measured approach to classroom tech.

“My sense is that they haven’t thrown it all away, nor have they overdone it,” he says, referring to the general balance of the UK’s tech approach. “Some areas could be better, like using more print textbooks.”

What’s the best way to employ digital tech in classrooms?

One of the things that makes this area so messy is that technology can cause and amplify behaviour and pastoral issues, which then have a knock-on effect on learning. Separating out those behavioural and pastoral challenges from the more direct impact of tech on learning is tricky. But recognising the difference is important; schools cannot ban tech in pupils’ homes and the spillover into classrooms is inevitable.

It’s a factor that needs to be considered when weighing up whether the risk of tech for learning in schools is worth it - asking, for example, how far the negative effects of tech on learning are down to personal phone use rather than the use of phones to aid learning in school.

To talk about tech in general is misleading. Instead, we need to talk in terms of specifics and context. When you do, you find some compelling evidence that tech can actually be helpful to schools and to learning.

For example, the most common use of digital technology in UK schools today, says Al Kingsley - a multi-academy trust chair, edtech CEO, and speaker and education author - is to keep the school running.

“Technology keeps the whole school ticking - the coordination and effective use of data, how we keep them safe online,” he says. Digital technology used effectively at the school level therefore gives teachers more time and space to do the important work of teaching and learning.

Tech can be used in other ways to support learning, too. Recent research on exactly what schools’ policies should be on students’ use of digital tech for learning - how they use it, when, for how long - shows that, above all, schools should have an overall understanding of how digital technology improves student learning, and why a particular digital tool would enhance learning over an analogue one.

Cathy Lewin, professor of education at Manchester Metropolitan University and co-author of the 2019 Education Endowment Foundation report Using Digital Technology to Improve Learning: Evidence Review, says their study highlighted how digital technology is an effective tool to supplement other forms of instruction. But to benefit, schools must consider exactly how technology will improve learning before introducing it.

Laptops and tablets are useful to practise specific skills in mathematics and literacy, Lewin says, such as multiplication tables or phonics. Other evidence-based digital advantages lie in modelling and simulation capabilities to enhance science and maths, and mobile apps for learning a second language.

“Evidence to date suggests that it is effective for maths, literacy and science,” Lewin says. “It is also effective for second language learning, particularly when using mobile devices.”

When it comes to a subject like English, however, tech usage might look slightly different. Laptops are useful for gathering information, such as evidence for an essay, says Frederick Hess, senior fellow and director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute and co-author of the Brookings Institute’s Realizing the Promise: How can education technology improve learning for all? But the work of generating thesis statements and sharing feedback should be done in class, human to human.

“Tech is useful for gathering and collecting,” Hess says. “But a large portion of time should be kids interacting. Instead, what’s happened is that tech is crowding out those interpersonal dimensions.”

Some schools might be leaning on digital tech for learning more than they need to, feeling pressured to maximise technology use after big spending on it during the pandemic. But when it comes to lessons on laptops, “it’s quality over quantity”, says Carolyn Sykora, senior director of standards for the International Society for Technology in Education. “[It’s about] knowing where, when and why to use tools to meet the teachers’ objectives for students.”

Digital technology also appears to be beneficial for teachers, often saving them time. A 2020 report from McKinsey and Company, a global management consulting firm, showed how automating technology, often produced by artificial intelligence, could help teachers plan lessons, grade homework, assess student progress and complete administrative paperwork faster - saving them up to 13 hours a week.

UK-based software program No More Marking doesn’t use artificial intelligence but still says it is helping teachers to grade written essays in a more equitable way - and is saving them time in the process.

The technology uses an analogue concept called comparative judgement, in which teachers compare writing from different students. In large national assessments, No More Marking then gathers teacher responses - from thousands of teachers who have made hundreds of thousands of comparative judgements - and combines them, producing faster and more consistent grading results.

Schools are using the technology to not just make grading more efficient but to compare their student outcomes with nationally representative samples.

One user of No More Marking, David Didau - the English lead for Ormiston Academies Trust, a national network of 42 primary and secondary schools - seems generally sceptical of edtech overuse in classrooms. It’s often “a solution in search of a problem”, he says, and, when used poorly, can widen attainment gaps instead of closing them.

But Didau says certain tech is useful when it can improve how teaching and learning gets done. Ormiston is using No More Marking not just to assess student writing but to help teachers advance instruction quality.

“When done properly, it’s not just used to gather assessment data, which is useful. But when it’s used best, it’s teacher quality assurance of their own work,” Didau says.

Daisy Christodoulou, director of education at No More Marking, says the software is meant to help teachers give more effective grades that increase student learning. Students don’t even need a computer to participate; teachers can scan in handwritten essays as well as typed ones. “What we are trying to do all the time is square the circle - deliver efficiencies without students being distracted by screens,” she says.

Going beyond a replacement for pencil and paper

But experts interviewed for this story seem to agree on one thing regarding digital technology in classrooms: most schools aren’t using tech in more innovative ways to increase or enhance learning. Hess and co-authors of Realizing the Promise point out that most often, laptops and tablets are being used to replace traditional classroom analogue tools such as pencil and paper. Some of this tech has clear advantages - “helping to scale up standardised instruction, facilitate differentiated instruction, expand opportunities for practice and increase student engagement”, they write.

However, some suggest that using computers only as digital organisers is missing some of tech’s most important capacities for aiding learning.

Schools might consider innovations such as EarlyBird, an online dyslexia screener and literacy assessment tool. It was created by cognitive scientists as an interactive online game to gather data about exactly which phonemic awareness skills students are missing, so teachers can target instruction individually. Or Ignite Reading, a face-to-face online tutoring platform zoomed into classrooms to provide individualised reading instruction to 30 students at the same time.

But beyond innovative software, researchers say teachers are often unaware of what the digital tools they have can do. They may also come to technology with a host of beliefs, both positive (“students are digital natives”) and negative (“computers are making students less intelligent”), and, as research shows, that may hamper their ability to clearly see effective uses for digital technology.

To get the most out of digital tools, experts say, schools need a plan and teachers need training. According to Lewin, much existing teacher training isn’t successful because it focuses on tech-savvy rather than more practical pedagogical uses.

“Given that the use of edtech is very much dependent on context,” she explains, “more on-demand generic training, not related to specific products but focusing more on kinds of uses, would be helpful. Helping teachers identify which training might be most beneficial would also be helpful.”

So, rather than asking whether or not we should be rowing back on tech in class, as Sweden is, it might be more helpful to consider what the education sector needs to implement to make sure tech is supporting learning effectively.

For instance, a school-wide plan for how technology is used, along with a knowledgeable instructional coach or point person leading the technology, would make laptops and tablets more purposeful, Kingsley says.

Clearly, there are instances where paper and pencil are still best, he adds. But schools should be hesitant to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

“At the end of the day, we don’t get a choice within our education systems in our country, to decide what are appropriate technical skills to impart to our learners. When our children leave school, they will be competing with children from all around the world who have those digital skills and those experiences,” Kingsley says. “I don’t think Sweden is right.”

For the latest research, pedagogy and practical classroom advice delivered directly to your inbox every week, sign up to our Teaching Essentials newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters