I was on holiday once, looking at one of those community bookcases you get by the swimming pool, full of other people’s beach-book cast-offs. I had read whatever novels I had taken with me and needed something new. For a book snob like me, the options were bowling-shoe ugly. I hummed and hawed, dillied and dallied, and ended up with Katie Price’s 2005 autobiography, Being Jordan.

I don’t know what I was expecting; I wasn’t expecting much. But the book delivered. It zipped along at a good pace, it kept my attention and there was something endearing about the earnest narrative. It was pure literary popcorn, ideal for my situation.

I was thinking just this before the summer, when I read Katie Fraser’s recent piece in The Bookseller about hierarchies of writing in society. She argues that labelling books as “highbrow” or “lowbrow” is counterproductive - it’s the act of reading itself that matters.

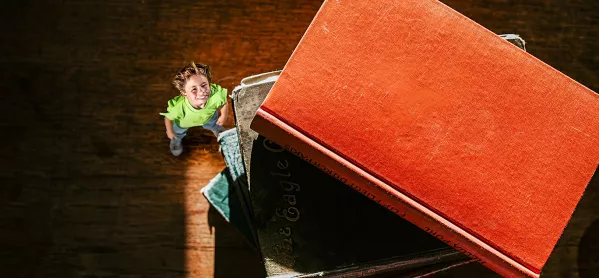

This certainly tugged at a common thread I have come across. The challenge of getting teenagers to read for pleasure is a recurring issue for discussion at parents’ evenings. We are well aware of the competition: mobile devices with their tempting bursts of social media-fuelled dopamine, online multiplayer all-nighters spent blowing up tanks or winning World Cups, scrolling TikTok for that one infuriatingly elusive close-up video of a cat’s scrunched nose.

I often hear that children used to read all the time, when they were pre-teen, but now have to be cajoled into it. I was like this myself, enduring a barren period where I read only what my teachers put in front of me, yet coming out at the other end with a proper taste for what I liked as an adult.

I advise parents not to worry too much about the material their children read. Rather they should provide a variety of options - memoirs, journalism, true crime, short stories, poetry, as well as the more traditional books. Graphic novels and comic books have their place, too.

Getting pupils reading is more important than pushing the classics. I try to find out the interests and hobbies that might motivate individuals, and we also provide a recommended reading list for all stages, taken from suggestions from former students and staff.

Nevertheless, there will still be those who struggle to get into reading. For these students, we have to create a vibe (as the kids might say). We can try to gamify reading by setting up challenges or offering points, putting classes into reading competitions against one another, encouraging inclusion and diversity through careful promotion of under-represented authors.

Above all, reading should never be used or seen as a punishment.

Reading needs to be modelled by adults. Children should see their teachers reading, see their parents reading, read with their families. This is something that can nurture wellbeing and combat the ever-increasing anxieties felt by nearly all of us.

Happily, it’s not all bad news. Apparently, children read almost 25 per cent more books last year. Social media, and TikTok in particular through it’s #BookTok community, have opened up unexpected pathways for trending books and authors, breathing life into the young-adult publishing world.

Evidently, reading does remain popular for some young people, and our priority should simply lie in encouraging the act of reading rather than imbuing any sense of snobbery or inherited elitism.

Alan Gillespie is principal teacher of English at Fernhill School, near Glasgow, and a novelist