- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- How to...tackle ‘rape culture’ in schools

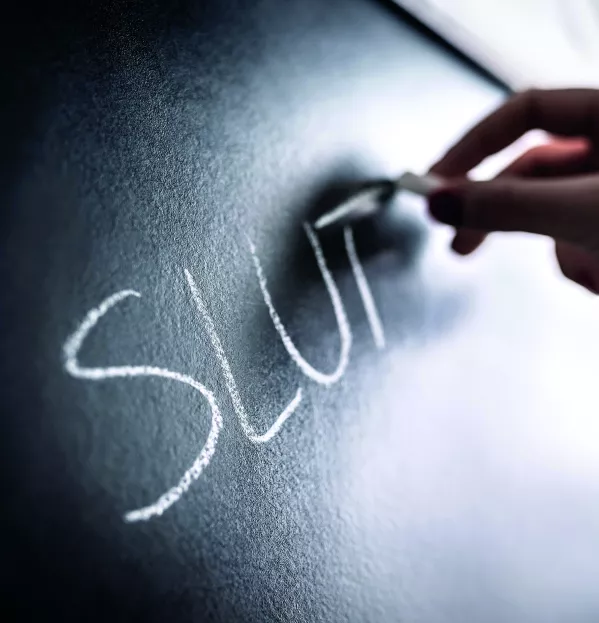

How to...tackle ‘rape culture’ in schools

Until recently, “rape culture” was not a problem that was talked about in schools. Now, however, it is being talked about everywhere. It is something that is happening in every school. It is happening in your school.

Since March 2021 over 15,000 testimonials of young people’s experiences related to rape culture have been shared on the Everyone’s Invited website. This has sparked a debate about how schools respond to the issue.

So, what should schools be doing to stamp out rape culture? We spoke to Sophie King-Hill, senior fellow at the Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, to find out.

Tes: What do we mean by ‘rape culture’?

Sophie King-Hill: The term “rape culture” refers to the tolerance and normalisation of toxic sexual behaviours. It refers to myriad sexually motivated acts, including sexually derogatory jokes, coercion, misogyny, touching without consent, online abuse and actions involving photographs (ie, up-skirting and the sharing of sexual images).

The normalisation of such behaviours within wider society and schools lays the groundwork for these behaviours to evolve into more violent non-consensual acts, such as rape and sexual assault.

What does research tell us about how big the problem is?

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), harmful sexual behaviour in children and young people is rising.

Reported sexual assaults between peers rose from 4,603 in 2013 to 7,866 in 2016. And in 2017, across the jurisdictions of 38 police forces, there were 30,000 reports of children and young people assaulting each other, with 2,625 of these being carried out in schools. Yet only 26 per cent of these reports resulted in intervention across 36 police forces.

Earlier this month, an Ofsted review of sexual harassment in schools found that nearly nine in 10 girls said that they or their peers were sent unwanted explicit pictures or videos they did not want to see “a lot” or “sometimes”, with nearly 50 per cent of boys reporting the same.

And 92 per cent of girls and 74 per cent of boys said that sexist name-calling happened a lot or sometimes to them or their peers.

Is the issue really worse than it used to be? Or is it simply a case of more incidents being reported now?

It is difficult to say if this problem is actually growing or if, owing to recent awareness, more individuals now feel confident to speak out. The rise of social media has made it much easier to report and discuss incidents under the protection of anonymity.

The data does suggest that this is an increasing problem. However, measuring this accurately is difficult, as many instances may still be going unreported.

Covid may also have had an impact here. Could you explain what effect the recent lockdowns have had?

For many young people, school is the only avenue where they can access robust, clear and concise information concerning relationships and sex. The school closures shut down this support for many.

And with students now back in classrooms, we run the risk of relationships and sex education (RSE) falling by the wayside as schools focus on catching students up in “core” subjects.

So, where does this leave schools? The catch-up pressure is not easing up, and many would say that tackling rape culture needs to start at a policy and society level

As schools struggle to pick up the pieces that numerous closures have left, there will be many gaps to fill and they will need support to do this.

Ideally, we need a national approach to reducing rape culture in schools in the form of a package of support and resources that recognises the recent shortfalls in RSE. There has to be a joined-up policy approach to this issue, with everyone working together to combat it rather than leaving it to individual schools to manage.

Until a national policy emerges, what steps can schools take now to create a safer environment for all students?

The first step will be to recognise that these issues are very real and that they exist. This may be done on a school level by involving the governing body and opening up conversations about the problem.

RSE has to be prioritised alongside other subjects, such as English and maths.

However, it’s important for school leaders to recognise that many educators may not feel comfortable talking about these issues in the classroom. Teaching RSE is not for everyone and schools must allow educators to opt out, while giving all staff opportunities to access support and training in this area.

Robust safeguarding standards and policies should also be in place, which refer directly to issues related to rape culture. There should be dedicated members of staff to deal with incidences as soon as they arise. Any reports made by students should be taken seriously and acted upon accordingly.

Schools should also engage with the wider community, for example, by involving parents and carers, local agencies, sports and youth clubs in working together to combat these issues.

But one of the most important things that schools can do is to listen to young people and use what they say to inform their work in this area.

Schools need to recognise that all genders have a voice and that a blame culture can be detrimental. While there should be consequences for actions, restorative approaches may be the best way forward when it comes to tackling rape culture in schools successfully.

Does that mean that men and boys should not be asked to shoulder the blame?

Boys and men should not be asked to shoulder blame collectively. Blame culture is damaging for everyone. While there is evidence that the majority of incidents related to rape culture in schools are carried out by males against females, we need to take a wider perspective.

The impact of what we call “toxic masculinity” - and the expectations placed on young men to be dominant, aggressive and powerful - feeds into the issue, as it reinforces stereotypical ideas of “manliness” that boys must live up to in order to be respected and validated within society. This can also inhibit boys coming forward when they have been a victim of sexual aggression.

Yet, to approach the situation with blame towards a certain gender is counterproductive. The best way to combat this very real problem within schools is first to take it seriously on a national and school level. We need to create open dialogue and to work across all genders to listen, support and educate everyone about this issue from a young age.

Sophie King-Hill is senior fellow at the Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham

This article originally appeared in the 25 June 2021 issue

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article