- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Inside ‘the most expensive school in the world’

Inside ‘the most expensive school in the world’

The grounds of Institut auf dem Rosenberg are pretty but not showy. A leaf-covered lawn is dotted with garden chairs and edged by neat potted shrubs. The plain cream façade of the modest main building is swaddled in climbing plants, a mint-and-white striped awning providing a little shade and shelter if needed.

At first, then, it feels more spa retreat than school, and there is little sign of opulence. Yet, the obvious question is never far from your mind: where is the money?

The understatedness of the surroundings may come as a surprise since Rosenberg is routinely described as the most expensive school in the world. The average annual fee for students, who are all boarders, is 150,000 Swiss francs, or about £133,000 at current exchange rates. And this is not something the school shies away from talking about.

One of the frequently asked questions on the school website enquires bluntly: “Is Rosenberg the most expensive school in the world?” The reply is coy but not exactly eager to refute the suggestion: “Possibly, but we don’t lose any sleep over this question since, frankly, it is irrelevant to us. We work hard to be the best boarding school in Switzerland and the world, rather than the most expensive one.”

The school for students aged 6-18 - founded in 1889 and sitting on the edge of the Alpine town of St Gallen - asks that I quote only Bernhard or Anita Gademann, the husband-and-wife team who are the fourth generation of the family that has run the school for almost a century. The reason given is that “we do not want to focus on individuals but more on the school as one”.

Before I meet Bernhard Gademann, the school’s president, I am taken on a tour, with two of the first stops being a tidy ICT suite and a small gym. Rosenberg claims to have been the first school in the world to have a gym and, with its exposed wooden ceiling, it looks in scale and design like the ones I knew going to tiny rural primary schools in north-east Scotland in the 1980s (apart from the huge period mural of gambolling children on one wall).

It’s all very nice but, on the surface, unremarkable, so I am upfront in reminding my guide of my overriding question: what does an education this expensive buy that you wouldn’t get in other schools?

The response is a reroute to see what I’m told is the tallest 3D polymer structure in the world (picture below). Standing at more than 7 metres tall, I have to look up to take in something that looks like it has been lifted from the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey and plonked onto the green, green grass of a Swiss idyll.

Inside, students can simulate a space habitat on the moon for up to 48 hours. They communicate with a “mission control” operated by SAGA Space Architects in Copenhagen - which also helped students design the space habitat - and with an extreme environment psychologist in London who works for the European Space Programme. The bespoke design features were conceived by pupils themselves: lights that follow the circadian cycle, an anti-fungal cork interior and wool storage pockets, the latter made of recycled clothing and suggested by an eight-year-old. There are also plans to add a comforting collection of sounds and smells from Earth’s forests and oceans.

I ask how much all this costs. Without being given specifics, the answer is assuredly “a lot”. The same goes for Spot, one of Boston Dynamics’ doglike robots that students can command to carry out tasks - from the space habitat and elsewhere in the school - using QR codes, and for what looks like a mini-Eden Project, where students explore myriad scientific and environmental concepts. The money does not immediately scream at you on arrival at Rosenberg but it’s plain to see on a stroll through the grounds.

What’s most remarkable about the space habitat is the speed of execution: from an original idea by pupils for a spacecraft simulation through to design, construction and the working structure I am squeezing my long frame into, it took just nine months. I know people who have taken far longer to get a garden shed built.

It all echoes the aspirations of Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) - with its emphasis on interdisciplinary and child-centred learning - which I have been writing about for many years. Only here at Rosenberg, money is no object in realising such bold aims; neither are class sizes, rigid timetables or entrenched exam-based approaches to assessment. Rosenberg offers a range of qualifications including the International Baccalaureate, English A levels and US Advanced Placements but I am told that “values are as important as exams”. Exams are seen as a necessary evil, offered in pragmatic but weary acceptance that they are a currency that opens up university and employment.

Classes have an average of eight students per course - although many have 1-5 students - and a staff to student ratio of 1:2. Rosenberg has 230 students and 230 timetables, I am told. Each student has an “individual development plan” which is constantly refined in up to three meetings a week with a staff mentor. A timetabling app developed by the school means, says Gademann, that “in theory, you could have a new timetable every day of the week”.

The parallels with CfE’s rhetoric are uncanny: the dismissiveness about “subject silos”; the mantra that “we’re preparing kids for skills that they’ll need in 12-15 years”; the vaunting of creativity; the idea that teachers are guides on the side rather than omniscient dispensers of wisdom. Such is the discomfort about traditional notions of teaching that I am reminded frequently that there are no teachers here - instead, Rosenberg has “artisans” (for more on the thinking behind this, click here) characterised by their “flexibility” and “entrepreneurial mindset”.

Entrepreneurialism is lauded at Rosenberg: students’ parents are “basically all entrepreneurs”, says Gademann at the end of my visit last autumn, adding: “They are an exceptional source of inspiration for us, really, because they’re working in leading industries and they are industry leaders themselves - whether that is philanthropic organisations or in tech doesn’t matter.”

He recalls one father who was weighing up several potential schools for his child, but seemed disappointed to arrive at Rosenberg and see no Bentleys lined up at the front gate or designer handbags adorning students’ shoulders. Unimpressed by this lack of ostentation, he quickly decided to go elsewhere. He had perhaps also clocked the pink railings that hint more at Willy Wonkaesque inventiveness and eccentricity than an education of gilded privilege and austerity.

“A Chanel bag is not an achievement,” says Gademann, whose school champions environmentalism over conspicuous consumption: “wind trees” on the grounds that charge battery-driven school cars and students’ 3D-printed ceramic brick prototypes will testify to that - the latter are already being put to use in an attempt to regenerate coral reefs at Magoodhoo island in the Maldives’ Faafu Atoll, and at Colombia’s San Andrés island.

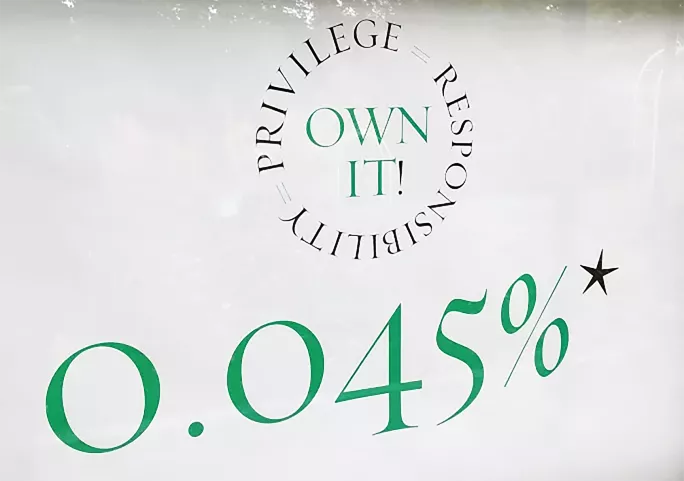

A sign in the central outdoor area reminds students each day that “privilege = responsibility” and that they should “own it!”. In a much bigger type underneath is the figure 0.045 per cent and an asterisk drawing the eye to this: “percentage of the world’s population that can afford to study at your school”.

I ask if there is a contradiction in staff constantly telling students they should leave school determined to make the world a better place, while at the same time providing an elitist education with advantages unattainable to the vast majority of their peers around the world.

“Yes, our students are from privileged backgrounds [but] we also tell our students repeatedly that, consequently, we have higher expectations,” says Gademann. Students are told that being privileged is not a problem - not being aware that you are privileged is the problem. And during my visit there are numbers of allusions made to a certain type of perceived UK public school ethos - the encouragement of a sense of superiority and entitlement, whether explicit or implied - that Rosenberg is keen to stand apart from.

Gademann is disdainful of exams - “in the long run, they’re truly obsolete” - and insists that Rosenberg’s success is measured by whether parents are happy with their children’s development, although the school does point to students’ high grades in various exams as evidence that “their learning is enhanced in relevance through its real-life context”.

The school’s income is entirely generated by fees from families - business and philanthropic donations are not accepted - and this financial independence is seen as crucial: “We often say we are a 134-year-old startup…the privilege that we have with financial resources allows us really to pioneer new methods of teaching.”

Gademann posits that “traditional education” often “lacks bravery”, but that this is not the fault of teachers or school administrators: “The individuals within that school may have great ideas but they work within a system which, if you try something and it doesn’t quite work and the exam scores go down, then it’s a problem.”

Teachers at Rosenberg - the “artisans” - must prepare for the unexpected.

“Neither the student nor the artisans very often know what the outcome of the experiment is,” says Gademann (pictured below), with the space habitat being the prime example of this approach. The school want staff who are “not afraid of saying ‘I don’t know the answer’”, who avoid “taking a cookie-cutter approach” and are “open to a constant evolution of what we teach and how we teach”.

The Covid pandemic took that to another level. Gademann says Rosenberg was the first school in Switzerland to send students home, and that it immediately started a switch to live online learning.

“By that I mean that each student had a timetable that covered all the time zones of the world, from Japan to the west coast of the United States,” he says, which could lead to teachers working at 2am their time.

Then, once restrictions eased, staff and students returned to Rosenberg during what should have been the summer holiday, to ensure they could make up for anything they had lost during the huge disruption of spring 2020.

“So, in effect, our students received more lessons and hours of instructions than they would have without Covid.”

The school encourages a sense of “constant change”, epitomised by an outbuilding that is moveable in all directions, with unfixed furnishings that can be renconfigured any which way, and a cinema-sized screen that operates as a giant pinboard for endlessly shifting projects; the rationale is that if ideas are flexible, learning spaces should be, too.

It also strikes me at a certain point that the school never - on its website or during my visit - refers to its alumni. Past achievements “don’t mean anything now”, I’m told, and having had family members go to the school in the past is no guarantee that your own application will be accepted.

Past achievements are “not a guide to the future”, says Gademann, who acknowledges the stark contrast to the fairly standard practice of schools talking up their high achievers of the past. “Traditional schools, particularly in the UK, celebrate this as an example of their elitism but this is exactly what we don’t want to do.”

Pink neon lighting in the school dining room spells out the words: “This is our time.” The past, says Gademann, is “frankly irrelevant because, as a school, we’re only as good as we are this school year”.

Henry Hepburn is Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland editor at Tes. He tweets @Henry_Hepburn

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article