Why you can’t separate attendance from mental health and SEND

Share

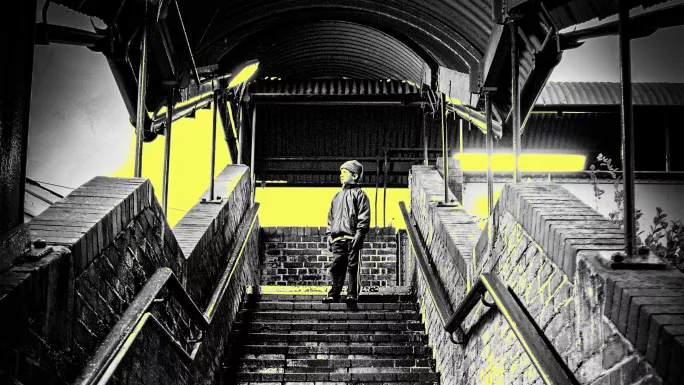

Why you can’t separate attendance from mental health and SEND

This article was originally published on 11 September 2024

As the education world continues to wrestle with an attendance problem of epic proportions, the question of which solutions will actually work looms large. Policymakers are opting to take a primarily punitive approach to the issue, with increased fines for parents if their children are away from school.

But is this the right way to tackle the crisis? Tamsin Ford, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, argues no.

Instead, she tells Tes in our interview below that schools need to recognise the complex interplay between mental health issues and special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) that can be powerful driving forces for absence, along with challenging home circumstances, and take a collaborative stance to address these.

Tes: What do we know about how attendance is linked to mental health and SEND?

Professor Tamsin Ford: We know there is a bi-directional relationship between mental health and attendance at school: if your attendance is poor, then your mental health may well deteriorate because you lose the chance to connect with peers, and so you become socially isolated [and less likely to attend school].

And there’s a complex relationship with SEND, too. Children with poor mental health are seven times more likely to have SEND and six times more likely to have an education, health and care plan.

Also, poor mental health - particularly anxiety or depression - can undermine a child’s ability to focus and motivation to learn, causing problems in school that can lead to needing additional support. And having a specific or global learning difficulty also increases a child’s chances of having a mental health condition, because they have to work so much harder to keep up with their peers.

Is that link between SEND and mental health something teachers should be expected to spot? Does SEND make mental health diagnoses more difficult?

The relationship is complex. Autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder are both mental health conditions and can cause SEND; poor physical health is a risk factor for mental health conditions (particularly if the health problem affects the central nervous system, such as epilepsy) and can lead to SEND; learning problems are separately a risk factor for mental health and struggles with the school environment, with issues like bullying more common among children with SEND, which can precipitate mental health conditions.

It would be helpful if teachers were aware of these complex interrelationships and kept a high level of alertness for potential mental health conditions among pupils with SEND.

You said SEND and mental health can drive attendance issues, but attendance issues can also contribute to SEND and mental health challenges: is it important to work out which came first or should it simply be accepted in schools that these three areas will almost always co-exist?

Very much the latter. A PhD student of mine developed a model of a coping continuum, which is an amazing concept. Essentially, it highlights how these children have complex journeys through school, with phases of better and worse coping.

Establishing a simple cause and effect is not likely to help as they are unlikely to be on a linear trajectory; most children will have got into negative cycles, so the important thing is to try and leverage strengths within the individual, family and school to get a virtuous cycle going.

How did Covid-19 exacerbate this crossover of issues that are linked to attendance - more undiagnosed SEND, not attending school became more of an option, a lack of intervention in mental health concerns at early stages?

I don’t think we can be entirely sure yet. We know that certain vulnerable groups found accessing school remotely easier to cope with and so struggled with the return. It’s also possible that more vulnerable children may have developed SEND because of lockdown disruption.

Plus, both SEND and mental health services are swamped, so responses have been slow and problems may have escalated. But more research is certainly needed to have a clearer picture.

Are there any examples of increased screen use playing a role?

One interesting element is from talking to audiologists, who say there has been an upswing in children where it’s really difficult to test their hearing because they don’t really respond to humans, they respond to screens. And that may be because they would sit in front of a screen while their parents worked, sometimes for hours.

The knock-on effect there is that if your language is a bit delayed, then that sets up reading to be a bit delayed and then if you can’t read fairly fluently by the time you get to secondary school, it becomes a really difficult place to be.

There are some cognitive reasons why that could happen, and some developmental reasons why, but also, I think there are social reasons, particularly the pressure on parents to work during lockdowns with no child care.

Another example of social factors influencing mental health, and in turn attendance, is bullying.

Probably our most tractable mental health risk factor is bullying, which we know is a major factor in school avoidance. So it’s important to have a really strong anti-bullying policy and follow it through.

It is so unusual for a conflict to grow out of just one person behaving badly; there are misunderstandings, miscommunication and bad behaviour on at least two people’s part. But actually, if bystanders didn’t stand by and just let things happen, and they spoke up, it would make such a big difference. And yet we tell young people not to tell tales.

What would you suggest schools do to get better at looking for SEND and mental health links to attendance?

I was at a Place2Be roundtable recently and one of the speakers described a situation where a child was in school only 40 per cent of the time. A simple check of the register showed it was on the same two days every week.

This child was in a secondary school where the uniform code was really strict, and basically was sharing shoes with her mother. So when her mother had to go to work, she didn’t have shoes, so she couldn’t go because she’d be in trouble at school. The sensible option, in that child’s world, is to stay away.

This is why it is so helpful to have attendance mentors; people whose role it is to zoom in on children whose attendance is wobbly. They focus their efforts not on the really severe absentees, but those where they’re either just above or just below persistently absent, because they feel like that’s where they can make a difference.

And the idea is to try and understand the reason for the lack of attendance and to see if there’s something fixable. A pair of shoes is really fixable, for example.

I think it says a lot about the rigidity around behaviour and uniform that the child and the family couldn’t have a conversation about it, or the staff couldn’t pick up and quietly say it’s OK. But they probably don’t feel able to.

A punitive approach is rarely helpful because what you really need is to work together as a team: the school, the parents and the local authority. And as soon as there’s a punitive element to it, you are breaking down that partnership.

The link between attendance and mental health or SEND seems intuitive, but how clearly do you think those links are being made in the attendance debate at a national level - there seems to be an assumption of parent choice with fines being a key “solution”?

We know that many parents believe they have no other choice, so fines are not likely to help; going down the punitive route is rarely the answer because so often there are other, complex issues.

And there are certainly other voices that need to be heard in that debate. That roundtable brought together people from different sectors, with different experiences and opinions, to think of solutions, and it came up with some really good recommendations.

Take that mother who can’t afford to buy her daughter’s school shoes: a fine is not going to get that child into school. Sitting with the mother and thinking about budgeting and where she might get some school shoes from - or even just someone buying the child a pair of shoes - would have sorted the problem.

Teachers can feel ill-equipped to talk about SEND and mental health - what would be your advice for exploring these issues sensitively in schools where attendance has become an issue?

The problem for children with SEND is that they are essentially having to do a marathon every day when other children are doing a 5K.

The more you struggle at school, the harder and the more exhausting it is, and the harder you have to work. Therefore, I suspect their struggles in coping with that situation lead to more extreme differences in behaviour, in what they manage to produce in terms of school work and perhaps also attendance at school - and it is useful for educators to keep that in mind.

MindEd and Place2Be also have a wealth of information that teachers can access to equip themselves with knowledge.

Is it the case, though, that sometimes not attending is simply a choice or behaviour issue and if so, how easy is it to spot when mental health or SEND is not a factor?

It is safest to assume that there is a problem that needs solving and that is more likely to be SEND, mental health or bullying, or some other adverse experience. Curious exploration will reveal issues in most cases.

Attendance problems can be about children being worried about their parents, for example. A child may not want to come to school because they’re not sure that their mum is coping, or that she has enough to eat, or they’re worried that she will be assaulted by her partner. And they want to stay at home and look out, and that will feed into attendance.

Obviously, you’re not in control of that as a school. You can try and influence it, and you can refer through to social services if you’re worried about child protection or safeguarding, but as educators, sometimes you can only be aware of what’s going on in the family that might be adding to all of this.

What you do have control over is how the school scaffolds general support, such as dealing with bullying or disagreements in a constructive way, and then offers deeper, individual support to pupils who are particularly struggling.

Do you have confidence that attendance, with the complexity you have described, is fixable?

Yes, the statistics are really frightening, but we should remember that, actually, the majority of children are doing OK. It’s just that the vulnerable group has gotten bigger in the past few years, and that affects teachers because I don’t think you can do your job properly for a child if their mental health is poor.

I know the mental health provision is woeful and that’s why things like whole-school approaches that might prevent the onset of mental health problems - like anti-bullying programmes and attendance mentors - are really, really important.

And relationships are key because we are social animals. Teacher-pupil relationships are a huge lever and so it’s important to try to have the most positive relationship you can with your trickiest customers.

There’s a famous study by Michael Rutter and David Quinton, who was a social worker, of young women in the 1970s who’d grown up in the care system. And there were two things that determined how they functioned in adulthood.

One was that at some point, at interview, they were able to name at least one adult who had a positive impact on them. And that was very often a teacher for these girls. (The other was how that, if they ended up in a partnership that was violent or abusive, or if their partner was delinquent or involved in crime, they ended up being dragged down.) That’s really powerful.

Teachers need to hold on to the fact that they are really important attachment figures, particularly for the more vulnerable. That might not necessarily show itself in warm relationships and good behaviour but don’t underestimate the impact that you as educators are having.

For the latest research, pedagogy and classroom advice, sign up for our weekly Teaching Essentials newsletter