- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

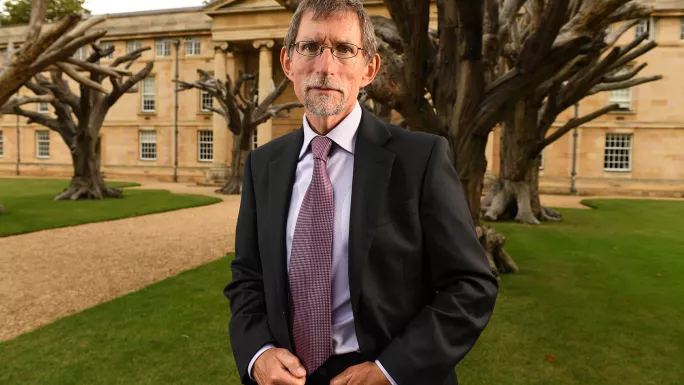

- Tim Oates: in defence of knowledge

Tim Oates: in defence of knowledge

Tim Oates has long championed the value of knowledge.

As one of the chief intellectual architects of the so-called “knowledge-rich” curriculum - Oates is the man who chaired the 2010 National Curriculum Review panel, which led to a significant curriculum overhaul in 2014 - his ideas are still having a significant impact on what is taught in classrooms today.

Those ideas haven’t always been popular, with critics complaining that an overemphasis on knowledge is squeezing “rich” learning experiences out of classrooms.

So, does Oates, who is the group director of assessment research and development at Cambridge Assessment, still believe that knowledge is king?

The answer, put simply, is: yes.

Almost 10 years on from the curriculum changes overseen by former education secretary Michael Gove, Oates is convinced that our curriculum is on the right track. He sees disciplinary knowledge as critical; “rich experiences” as a drain on teacher time; and cross-curricular projects as something to be avoided.

Tes sat down with him to find out more.

Tes: Most teachers will know your name primarily for your work on the national curriculum review, but you were thinking about what needed to change in our curriculum long before then. What are some of the ideas that first shaped your understanding?

Tim Oates: I studied philosophy and literature at the University of Sussex. At that time, Roy Bhaskar was teaching there and he had just written A Realist Theory of Science, which I was influenced by.

In essence, he differentiated knowledge of the natural world from knowledge of the social world. He proposed that there is an objective reality, which operates independently of human thought. Take gravity, for instance: no matter how angry or frustrated I am with gravity, it will continue to behave the way it does.

Because of this objectivity, our theories about the natural world can be used to explain or predict things that happen. For example, Boyle’s law is a law: you can use it to predict the behaviour of a gas at a particular pressure. If it’s a good law, it will be infallible.

The nature of the social world, on the other hand, means that the theories we have about it can actually affect that social world.

So, there is a fundamental distinction about reality in the social domain and the natural domain.

How does this relate to education?

In education, we can’t have the objective category of “predictive” knowledge, because our ideas cause us to act in particular ways and those actions actually make up and change the social world.

A very clear example comes from Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam’s work on formative assessment. They were commissioned by the education reform group to undertake a big international review of the literature and produced the incredibly powerful, brilliantly written Inside the Black Box.

But when they put their theories to the test in the King’s-Medway-Oxfordshire Formative Assessment Project, they found that the effect size they had predicted through the literature wasn’t visible in schools.

What became clear to Dylan was that the principles he had outlined were being knocked off course by the ideas that the teachers in the project already had. These ideas had been created by the accountability arrangements in the schools they had worked with.

For formative assessment to be a success, pupils need to reference their own past performance rather than compare themselves with educational standards expressed through qualifications - and this wasn’t happening.

It sounds like that might have implications for how we apply research to classroom practice. Do you think that it does?

What critical realism tells us is that even if an education policy is created in the light of really good research, to actually get the effects, you have to understand the constellation of effects and drivers in a particular context. You have to look at the ideas that teachers already have about ability, about pedagogy, and so on.

And even if a policy starts working, it can be knocked for six by something else, some other area of public policy, some change in the ideas of the actors within that system.

You started your career in the vocational sector. Did this also have an influence on your ideas?

Yes. In the late 1980s, I began working with Gilbert Jessup, a director at the National Council for Vocational Qualifications. Gilbert was driving a very strong doctrine of outcomes-based education into vocational qualifications.

At that time, it was felt that the qualifications had become divorced from the requirements of the labour context. Employers didn’t have much commitment to supporting trainees to gain formal qualifications.

‘To conclude that knowledge plays no role in day-to-day performance in the classroom would be wrong. Teachers need theories that explain what they’re doing’

Gilbert’s goal was to develop new sorts of qualifications based not just on programmes that were independent of work but also on what the work itself required. [Education researcher] Michael Young was very critical of this.

It was around this time he and I first came into contact.

Michael thought the outcomes movement was reductive, and I was very concerned about what I felt was a downgrading of knowledge.

How was knowledge being “downgraded”?

Gilbert’s idea was that we should focus on what somebody can do, and not on what they know. His argument was that you can infer knowledge from practice.

He was basing this on what the American military had done with their training. They’d adopted a very strong outcomes movement, which said, in essence: “You don’t need knowledge of firearms; you just need to relentlessly practise the cleaning and breakdown of firearms.”

The idea was that there was no need to start with acquiring knowledge as the first step in training because that knowledge would come automatically from extensive practice. Gilbert was convinced that if you assessed whether somebody could do something, you could infer from that whether or not they had the requisite knowledge.

Both Michael and I felt that was wrong.

What made you feel that way?

It was on the basis of research. For instance, someone I worked with in the 1980s had done a lot of work on nursing. Their research suggested that the values and attitudes of people in the care sector have a big influence on their behaviours, and their behaviours, in turn, really matter in terms of their clinical performance.

If you don’t care about people, it’s not a good idea to be a nurse. You probably won’t be a very good nurse. It will affect your performance - even if you have been practising nursing for years.

This goes back to Roy Bhaskar’s work about how our attitudes shape the social world.

And then another example is a study carried out by a colleague of mine, Keith Duncan. He had analysed what caused the 1979 Three Mile Island disaster, in which the reactor of a nuclear power station in Pennsylvania melted down.

His conclusion was that the disaster was down to a failure of knowledge. The people working at the reactor knew how to do the day-to-day stuff, but didn’t know what to do when things started going wrong. They couldn’t construct a mental model of what was occurring inside the reactor. The disaster was the result of a breakdown of knowledge, rather than practical know-how.

All of that adds up to thinking more about what we are putting in at the start of the process, rather than looking so closely at outcomes. That clearly has relevance for how we think about the curriculum, but might it also be important for how teachers are trained?

Yes. We had a tradition for a long time in this country of teacher training having a lot of theoretical components.

In some cases, those components and the focus on knowledge didn’t engage well with the reality of teaching, hence the shift towards more school-based initial teacher training. There was a disjunct and it was right to criticise that disjunct.

However, to conclude that knowledge plays no role in day-to-day performance in the classroom would be wrong. Teachers need theories that explain what they’re doing.

Can you give an example of how that plays out in the classroom?

As I was doing the national curriculum review, it occurred to me that teachers often have a very distinctive model of ability. It’s what enables the labelling of kids: this child is of “low ability”, this child is of “high ability”, and so on.

By the mid-2000s we were describing that in terms of levels. Kids were wandering around saying things like: “I don’t read the level 5 and 6 material because I’m level 4.”

It’s an idea, yet it became embedded in the system. Again, this takes us back to Bhaskar: the ideas determine the reality that plays out in the classroom.

Teacher training of whatever duration, whether it’s practice-based or based in university with practice components, must therefore engage with the ideas teachers hold about what they’re doing and about the kids they’re teaching.

You mentioned collaborating with Michael Young. Can you tell us more about the work you’ve done with him?

In around 2010, Michael gave a speech to The Prince’s Trust on what he called the “return to subjects”.

At that time, it was common to hear the differences between subjects described as if they were arbitrary - just distinctions made by humans.

The thinking was that having distinct subjects was problematic because it meant you had, for example, physics teachers and biology teachers who didn’t talk to each other. They downgraded each other’s sciences and taught kids in different ways, which led to the kids getting confused.

There was a feeling that we needed to reintegrate it all, by bringing subjects together in interdisciplinary projects.

‘If we say that teaching is not about disciplinary knowledge but about rich experiences, that’s increasing the workload of teachers exponentially’

The example I often give is a project on the National Grid. This sounds like a really great topic: it’s cross-curricular and integrates science with mathematics, geography with history, and so on.

The problem is that once you’ve got your list of coverage - of science and mathematics and geography and history and economics - you realise these ideas are only in relationship with one another because of the topic, the National Grid. This fragments knowledge.

What do you mean when you say it “fragments knowledge”?

There is a vital distinction in education between context and concepts.

Take mathematics, for example. In the National Grid project, you might teach proportion through a pie diagram or a bar chart showing how electricity is generated by renewables and non-renewables. If you want to develop mathematical understanding, you relate those charts to decimals, fractions and ratios.

Those ideas stand in a tight conceptual and explanatory relationship, whereas in the National Grid project, these things only exist in a contingent relationship, to do with that topic; they’re not related in any other way.

What students tend to take from interdisciplinary projects are memories about the context - in this case, the National Grid. The aim is for them to draw a strongly embedded understanding of various concepts, but instead, they are blinded by the surface features of the context.

We’re seeing these problems in Scotland at the moment, under the Curriculum for Excellence. The projects seem like rich learning experiences but the teachers are saying: “Actually, I don’t know what we’re really teaching.”

You’ve argued instead for approaches that focus on concepts practised across a variety of contexts. What might that look like in the classroom?

Negative numbers are a good example. Often, at primary school, kids are taught negative numbers through the temperature scale. You can tell them: “Zero degrees is a line and everything to the right of that line is positive and everything to the left of that line is negative.”

But temperature is just a context, and while it can help some kids with nascent understanding - and with some elements of how you make calculations, and what happens when you combine negative and positive numbers - conceptually, it doesn’t give the full picture of negative numbers, because it doesn’t convey the idea of absence.

What we need to do is take another context, to build that conceptual understanding.

It was [curriculum development expert] Richard Dunne who taught me this. The context he suggested was a house (which represents zero), with mounds of earth to one side of it. To the other side of the house are a series of holes; this is where the earth that makes up the mounds has been taken from. In this example, the kids can clearly see that as the holes (negative numbers) get progressively deeper, the mounds (positive numbers) get progressively bigger.

That’s a really nice context: an image you can fix in your mind, which also helps with the concept of negativity as absence.

What advice would you give to teachers who might be grappling with translating curriculum concepts into practice more generally?

I think it is teachers themselves who do the best job of systematically varying contexts in terms of a particular idea, like “conservation of mass” in science or “the unconscious” in literature.

If teachers seek professional development to make sure their own discipline knowledge is rock solid, that will help in their teaching enormously.

But policymakers have a role to play, too. They need to think about the kind of workload they’re implicitly and explicitly putting on to teachers.

If we say that it’s cheating to use a textbook, or that teaching is not about disciplinary knowledge but about rich experiences, that’s increasing the workload of teachers exponentially.

Let’s make what teachers do really simple, then we stand a better chance of them doing it well, and of retaining them.

A primary teacher once said to me: “I’ve been teaching the same science lesson for years. I’m really bored with it. I think I need to change it.” I said: “Does it work?” She said: “Yes, brilliantly.” I said: “Carry on, then. Just use it. It may be boring you, but it doesn’t bore the kids.”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

topics in this article