- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Why we’re getting formative assessment wrong

Why we’re getting formative assessment wrong

Hands up: what do we mean when we talk about formative assessment?

It’s a question that generates plenty of debate.

At a time when assessment in schools is under increased scrutiny, we spoke to one of the UK’s foremost experts on formative assessment, who says the term is problematic in itself.

“It shouldn’t have been called formative assessment; the word ‘assessment’ misleads people,” says Shirley Clarke, one of the profession’s leading lights on this classroom strategy who is speaking to Tes from this year’s World Education Summit.

“I like formative teaching and learning, because that’s what it’s all about. And I think that’s the problem. It’s that word [assessment] in there.”

So if this isn’t assessment, what is it?

What is formative assessment?

“Formative assessment is complex,” Clarke explains, “because it involves all the minute-by-minute information-gathering, from so many sources, all the time; me listening to what you’re saying, and then me interpreting that and thinking, ‘What do I do next?’

“The guiding force during lessons is, ‘I’ve got to get as much information from them as I can,’ because most of the time, children keep it all in. It’s got to be on the move, or walking around the classroom while they’re doing their independent work catching things, so you can actually get feedback in the moment.”

Read more: Formative assessment: a definition

Both summative and formative assessment have been commonly used terms in education since the 1960s, with the latter gaining more prominence in light of research by the likes of Fuchs and Fuchs in the 1980s and Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam in the 1990s.

Clarke claims this rise to prominence has led to an influx in “gimmicks” and a raft of misinformation, leading teachers to focus on individual elements of the approach or treating it as a short-term project.

Since then, she has spent the bulk of her career trying to address this. After leaving the classroom, she became a lecturer and researcher at the University of London’s Institute of Education. She is now a consultant and runs courses, carries out research and has co-authored with John Hattie.

Does formative assessment work?

Having worked closely with Hattie - a man who has built a career on looking for evidence - Clarke is in no doubt that this method has an impact.

“There is this fantastic body of research that underpins it all,” says Clarke. “The effect sizes for all the elements of formative assessment are all way above 0.4 [meaning they are above average on John Hattie’s table of influences on student achievement]. And it continues to be the single most important thing you can do to raise progress.”

And here lies another potential cause of confusion. As Clarke states, there are different elements that make up this method, which is why you won’t find her version of formative assessment on Hattie’s list of top outcome influences. You will, however, find the building blocks, such as pupil self-efficacy and classroom discussion.

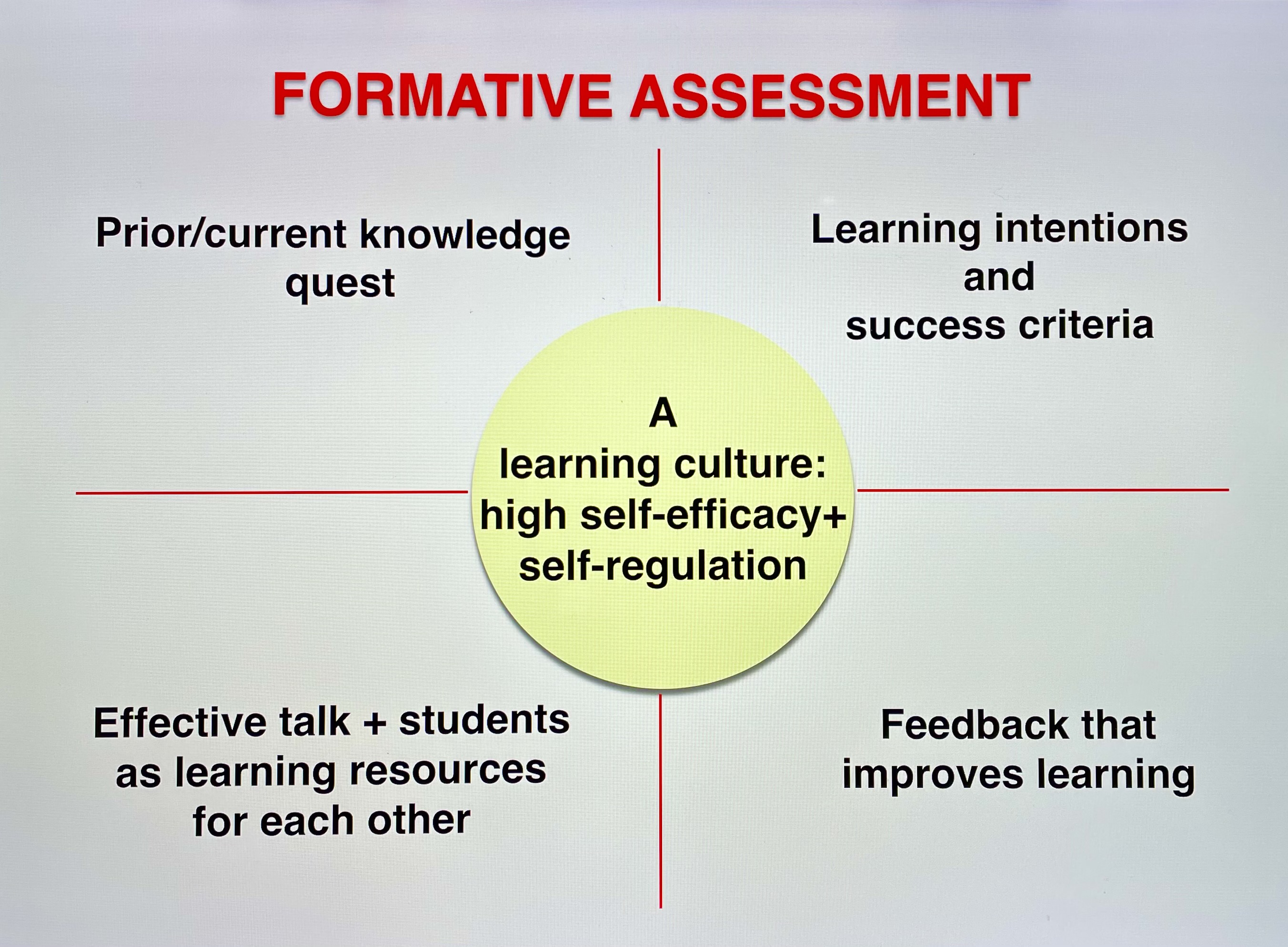

Clarke’s work has pulled together these different elements and presents them as a five-part, interdependent “jigsaw” (see below).

“In the middle is the learning culture and high self-efficacy,” explains Clarke. “Then you’ve got prior knowledge and current knowledge quest, learning intentions and success criteria, activating children’s learning resources for one another and great discussion, questioning and feedback.”

For Clarke, the interdependence of these elements is key.

“One of the problems is people hearing bits and pieces and cherry-picking. Their interdependence is phenomenal in terms of the outcome.”

Watch: Understanding formative assessment with Dr Shirley Clarke

Which elements make up formative assessment?

For Clarke, formative assessment is grounded in an understanding of what learning means, how memory works, children’s cognitive load and their ability to process new information. Also key is the development of self-efficacy.

“Self-efficacy is your belief in your ability to achieve,” explains Clarke. “Not your self-esteem, which is whether you think you’re a nice person or not.

“Self-efficacy is a really critical feature of being an effective learner. If you don’t have that belief that you’re capable of achieving, it doesn’t matter, for instance, how positive the feedback is that you get, you won’t believe it, you won’t react to it.

“Unfortunately, many of the systems that are set up in our schools seem to be designed to lower children’s self-efficacy; reward systems that compare children, ability grouping that we know demoralises children or makes them complacent and so on.”

Shirley Clarke’s formative assessment framework

A key part of creating self-efficacy is giving students clear success criteria, and in subjects where success is broader than right or wrong, this should include examples of what good looks like.

With success criteria laid out, it’s important to tap into any prior knowledge and link the topic to what has already been covered. This process only needs to last five minutes but can be crucial in how it shapes the rest of the lesson.

“The purpose of that first five minutes,” says Clarke, ”apart from sort of immersing them in the subject matter of the lesson, is for the teacher to straight away find out whether they remembered what we did yesterday, or last week - where their current understanding is.”

The next piece of Clarke’s framework sees students take an active role in learning, not just for themselves but for their peers, sharing ideas and having discussion.

“One of the big things about formative assessment is the activating of children to be learning resources for one another,” Clarke explains.

“Setting up effective discussion scenarios in the classroom. For instance, random talk partners that change weekly in primary or every six lessons in secondary, so that children over the course of a year have a fantastic range of both cognitive and social parings.”

Feedback is another big influence on student outcomes, but for Clarke and many researchers, it’s the type of feedback and students’ ability to interpret it that makes the difference. So, crucially, teachers need to focus on what works.

“Teachers have only got so much time,” says Clarke. “In the books that John Hattie and I wrote on feedback, we’ve really emphasised the power of in-lesson feedback, and minimising the post-lesson feedback.

“In the end, it’s about a balance of a professional judgement. What is going to actually have the greatest impact: spending two hours writing a comment on everybody’s book, or me doing most of that feedback as much as I can, during the lesson?”

It’s clear that impact underpins all of what Clarke advocates, and as schools return to full-time teaching it’s something educators will be desperately striving for. For them, her message is simple.

“Get back to what’s important: the learning and the impact of everything you do. Not the latest bandwagon, but actually stopping and saying, ‘What am I doing? What impact is it having on the learning?’ That’s the critical thing.”

Dr Shirley Clarke was talking to Tes at the World Education Summit. Tes is the official media partner for the event

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

topics in this article