- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Primary

- Could a class dog get children excited about reading?

Could a class dog get children excited about reading?

Archie, the labradoodle, is a real couch potato, according to his owner, researcher Jill Steel.

This, she stresses, is a positive characteristic: it means he is perfectly suited to his role in a study into children’s attitudes to reading, which she’s been conducting at the University of Edinburgh.

Last year, children in three Primary 5 classes in Scotland (equivalent to Year 4 in England and Wales) read to Archie for four weeks, while Steel tracked their wellbeing and attitude to reading.

Animal-assisted learning interventions have gained popularity in the past decade. Yet these approaches have often received criticism, being seen by some as little more than a gimmick.

Steel, though, thinks we would be wrong to rule such interventions out.

For the past two years, she’s been conducting research, funded by the University of Edinburgh’s Principal’s Career Development Scholarship, around reading to dogs. Her latest paper - the study mentioned above - has just been submitted for review.

On the surface, she explains, it’s a simple intervention.

“Reading to dogs involves a child or children sitting next to a fully assessed and registered dog, accompanied by a handler, and reading to it,” she says.

“Many children report they feel less anxious about reading to a dog than to a human, which increases their enjoyment and confidence in reading. The generally accepted rationale behind it is that the dog is a non-judgmental and comforting listener.”

It sounds straightforward, and it’s not hard to see why having such a loveable reading companion would appeal. But does it really work?

In order to test that, Steel began by finding out what teachers think about such interventions.

For a 2021 paper, Reading to dogs in schools: an exploratory study of teacher perspectives, 253 teachers (with varying levels of experience with such interventions) took part in an online survey.

Overall, perspectives were positive: 84.2 per cent thought reading to dogs led to a reduction in stress, and 60.9 per cent thought it improved reading frequency and skill.

Teachers also commented on children overcoming a fear of dogs, and promotion of citizenship through learning about dogs and dog welfare. Some said the experience was particularly positive for children with additional needs because of the sensory feedback and non-verbal communication with the dog.

Teachers highlighted challenges, too: 9.9 per cent had hygiene concerns and 36 per cent were worried about finding time in the school week to conduct the intervention. Concerns were raised about children (and staff) having a fear of dogs, allergies, dog welfare, the extra paperwork the intervention required, and cultural and religious considerations.

Overall, however, teachers were positive about the intervention, and Steel concluded their perspectives, and experiences, were needed to feed into any future intervention design and implementation.

For her next study, published in January, she worked with three teachers from different schools to design the Paws and Learn (PAL) intervention.

In this intervention, children would take part in weekly reading sessions with Archie and also have access to a package of resources, including a PAL notebook to use as they wished, and a box of 14 animal-themed reading books.

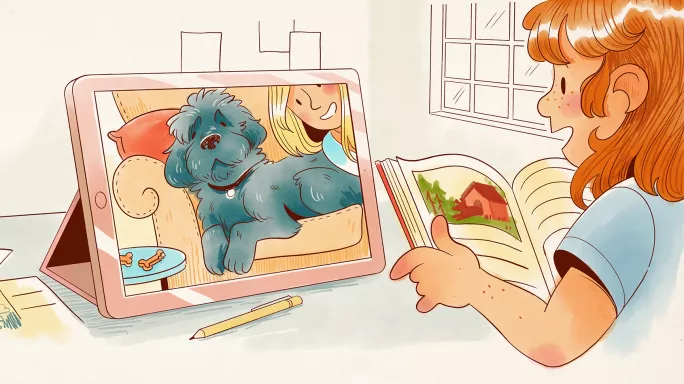

When it came time to test the intervention, the impact of Covid meant the trial looked quite different to what was originally planned - instead of Archie physically being in the classroom, he appeared over a video call.

Overall, 106 P5 children across three schools took part in the study.

Once a week, Archie and Steel connected to the classes via Zoom for an hour, and all the children had the opportunity to read to Archie. At two schools, the video call was on the smartboard, and the children took turns reading; in the other, the call was on an iPad, which was passed around the children.

- Michael Young: What we’ve got wrong about knowledge and curriculum

- Readability: a measure teachers should handle with care

- How to teach events of national significance

Students’ wellbeing and their reading outcomes were evaluated, as were their responses to the resources.

The results were mixed, says Steel.

“The quantitative results did not show any statistically significant impact on wellbeing and reading outcomes,” she says.

“There are explainable reasons for this; it was only a four-week intervention, and for real improvements to take hold you would really expect something to run for longer. It was during Covid, and so there were other factors impacting children, teachers, parents, and the school.”

The qualitative results, on the other hand, told a different story.

“The qualitative results, the interview data, were really positive. It was obvious to see the impact,” Steel says. “Every week the children were ready and excited. Some of the teachers said the children wanted to practise reading so they could be ready to read to Archie.”

Although it wasn’t what was initially planned, the online approach also had benefits. Any concerns around hygiene, fear and allergies disappeared, as did extra paperwork.

There are clear limitations to the research: it’s small-scale and results are mixed. Steel is clear: dogs are not a panacea to reading struggles, and using them within the classroom is a lot of work.

There isn’t currently any research that identifies which breed of dog works best either, she adds - dogs aren’t generic, and not all will be suited to going into a classroom.

She recommends that teachers who are interested in introducing reading to dogs speak to charities that specialise in this area, like Canine Concern Scotland Trust and Pets As Therapy.

“Charities have the dogs - who are often owned by retired volunteers - assessed and trained. They also visit other facilities like social care settings before they are considered ready to work with children,” she says.

“Some schools are choosing to bring in their own dogs to school, which is really concerning, not just in terms of risk to children and staff, but also to the dogs themselves.”

We can’t say for sure, then, that dogs make the best reading partners.

But as Steel suggests, if you are looking to introduce a furry friend to story time, it’s important that the recruitment process isn’t taken lightly: not every dog will be a great listener.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article