As we all begin to settle into a new era after the general election, it is time to consider new directions.

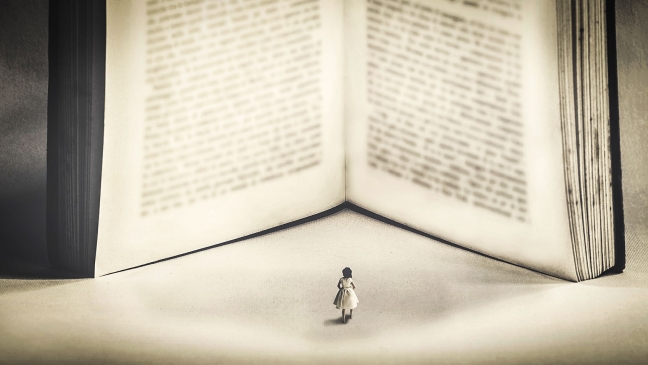

The past decade has brought a focus on knowledge, with curricula designed to help children know more and, in primary schools, know phonics. But by spotlighting some areas, others have been cast into shadow. One such area that deserves to be brought out into the sunshine is the development of reading comprehension.

Unlike word recognition, learning to read with comprehension does not involve gathering knowledge. Of course, there is some knowledge that helps with reading comprehension - knowledge of the world or knowledge of vocabulary - but reading comprehension is about knowing how to use this knowledge to understand.

Knowledge and reading comprehension

Reading comprehension is about the habits of thought that we adopt when we read. It is not about knowing words but knowing how to understand the words in the context in which they are written. It is about knowing when we do not understand and knowing how to repair our understanding. It is not about knowing how a text is structured but how this helps when we try to make sense of it. In essence, reading comprehension is not about knowing, it is about thinking.

So how do we help children to learn about reading comprehension? Teaching in small groups matters when we are teaching how to think through a text. Most of the research-evidenced teaching pedagogies that we use were designed for small groups, often to support children with reading difficulties. We cannot assume that these pedagogies translate into effective whole-class teaching; this may well demand new pedagogies.

More from Megan Dixon:

In addition, my research found that when teachers were asked about how they teach reading comprehension, most said they focus on introducing any new or unfamiliar vocabulary or the background knowledge students will need, and asking questions. In essence, they teach the knowledge of the text before allowing the children to read it and then assess it.

But to be confident readers, children need to recognise when they do not have that knowledge and therefore have to use strategies to work out the meaning. In other words, they need to fail at knowing things and, as teachers, our job is to catch them and show them the way through to comprehension.

So, in this new era, the next direction should be to focus less on knowing more, and more on knowing what is not known. Perhaps, if we are clever, knowing less might result in knowing more.

Megan Dixon is a doctoral student and associate lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University

For the latest research, pedagogy and practical classroom advice delivered directly to your inbox every week, sign up to our Teaching Essentials newsletter