- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Primary

- Q&A: BBC Newsround’s editor on pitching news to primary pupils

Q&A: BBC Newsround’s editor on pitching news to primary pupils

This article was first published on 9 September 2023

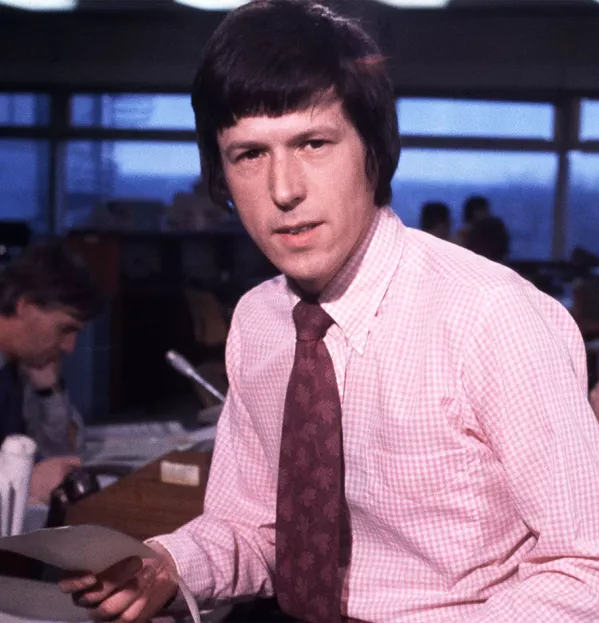

Newsround was first broadcast as John Craven’s Newsround on 4 April 1972, making history as one the world’s first news programmes aimed at children.

Now, 51 years later, it’s still going strong as a daily feature of classrooms across the country.

We spoke with the show’s editor, Lewis James, to find out how the team works with schools and serves its young audience.

How much do schools feed in to Newsround content?

It’s really important for us to know what’s going on in schools. Newsround fundamentally needs to be on top of the really big issues in schools but also what the latest playground crazes are and what the kids are into, so we talk to students all the time.

We’re in schools for filming a lot but we also visit outside of the filming schedule, and we will sit with classes and watch them watching Newsround.

The kids are pretty direct and they will tell you what they’re thinking, plus you can see if they’re not interested in something; you see the moment they switch off.

That’s really useful for us. We check comprehension as well as enjoyment: have they taken something away from what they’ve watched? Is there a different way that we can explain it?

We also get a lot of feedback from teachers, from emails and speaking to them in schools. It’s a two-way process, they tell us what they think we can be doing better or what they’d like to see in our coverage.

How do you work out how to pitch your stories?

Our target age is six to 12, so that’s a very wide range in terms of emotional and cognitive development. We are never going to have every single piece that we do - whether it’s the website or the bulletin or for our social media - that will hit every single part of that audience equally, so having a spread is important.

We start with a basis of no assumed knowledge, but also respecting the ability of our audience to be interested in things if we present them correctly, and to be able to absorb information.

We ask where the starting point of the story is and it’s often a few steps back from where you would normally work in news, as children don’t have the prior knowledge.

So, for example, take a general election. Our starting point would be: what is an election? How does it take place? What is the means of voting? And so on. In terms of pitching it, we’re always thinking about comprehension, and what’s right for our audience developmentally and emotionally.

How do you approach presenting difficult or upsetting stories?

With the most difficult things we do, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the difference between our content and other news content will often be the imagery.

That can mean choosing different pictures - so not the hardest-hitting pictures, the moment of death - and we think very carefully about showing distress, both in adults and children. We also have a variety of other visual techniques to use, such as graphics and animation.

This year we produced a new special 30-minute documentary on Ukraine and you’ll see all of those techniques there, and those careful choices of imagery.

Above all, when we’re considering how to do a story or whether to do a story, we think about how a child is going to come away from our content and how to put them in a better position to understand what is going on.

A lot of the feedback we get from teachers and parents is that the absence of information is more frightening for children than having the information delivered properly.

So, for example, on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, within hours we were getting parents and teachers telling us that there were all sorts of rumours going around social media and finding their way into the playground about nuclear war and other things.

What we don’t do is say “there is no chance of this war escalating” or “there is no chance of a nuclear conflict at any point in the future”. We couldn’t say those things, but we could say “there is absolutely no evidence that the UK will be involved in fighting in Ukraine” and “there is no evidence the war will expand at the moment beyond Ukraine’s borders”.

We can say that there are people worried about nuclear escalation, but other people saying it’s unlikely to happen for this reason, this reason and this reason.

We set it out and hopefully we can reassure with honesty, and leave them better informed and better equipped to deal with difficult news.

The show has been running continuously since 1972 - how is the landscape different now?

The decline in linear TV audiences has been a big change; the bulk of our audiences is now in schools. We have a much bigger audience now than we did 10 years ago, and they’re watching in school as a whole-class activity - maybe 25-30 kids in a classroom, watching together and being able to talk about it afterwards.

But fundamentally, if you watched 50 years ago, you’d recognise it as being the same thing today. The means of delivery has changed, and the subjects we cover change as times move on - and maybe the graphics look a bit different - but fundamentally, it’s the same thing, because it was a really good idea in 1972 and it’s a really good idea now.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters