- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Secondary

- What you need to know about the teenage brain, behaviour and phones

What you need to know about the teenage brain, behaviour and phones

This article was originally published on 13 September 2023

What drives teenagers to behave the way they do? The answer to this question has the potential to transform the work that goes on in secondary schools - and, for Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, getting closer to that answer is a lifelong passion.

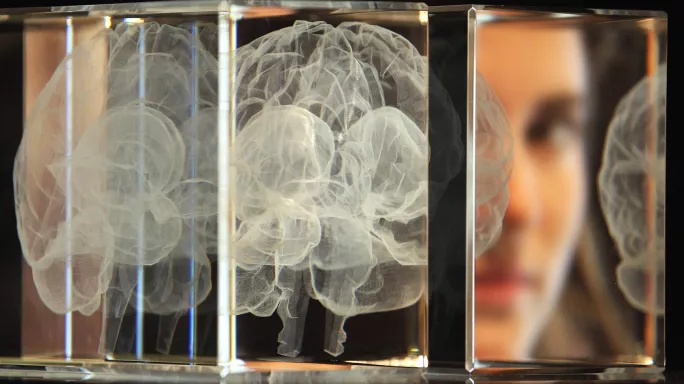

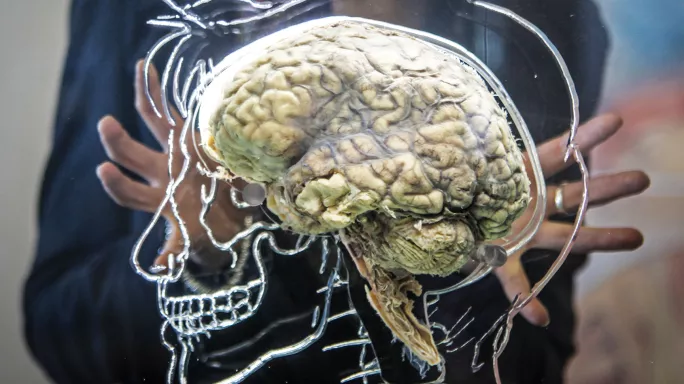

Her groundbreaking work in cognitive neuroscience focuses on the inner world of the developing brain, from its tendency towards impulsivity and risk to the need for social interaction and its links to mental health and wellbeing.

Her popular 2018 book, Inventing Ourselves: the secret life of the teenage brain, and her 2012 TED Talk, entitled “The mysterious workings of the adolescent brain” - which has now been viewed more than 4 million times - brought these complex ideas to a wider audience, promoting greater understanding of this remarkable phase of life.

Blakemore currently heads up the Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience Group at the University of Cambridge, where she is professor of psychology and cognitive neuroscience and runs behavioural and neuroimaging studies in the laboratory and in schools.

Tes sat down with her to hear the latest from the cutting edge of adolescent neuroscience.

It’s been 11 years now since your TED Talk. How has our understanding of the adolescent brain developed in that time?

The whole area has expanded exponentially. Eleven years is a long time in this field because the study of the adolescent brain and cognitive development is really only about 25 years old. But lots of labs have turned their research in this direction now.

If I were to give the TED Talk again, I would have a slightly different focus, probably on peer relationships and peer influence, and how peers start to matter a lot more to teenagers than they did as children.

Peers matter at all ages, of course, but there’s something about peers in adolescence that takes on increased importance and plays a role in decision making and risk taking, and all sorts of other things that adolescents do.

What are some of the new discoveries around those behaviours?

Anecdotally we’ve always known that teenagers are susceptible to peer pressure, but it has now been shown many times in lab-based studies, in epidemiological studies and from car insurance data - where they look at how having peers in the car affects young drivers’ chances of having a car accident, for example. It’s now an empirically established phenomenon, and I think that does change the way we approach adolescent-typical behaviour and adolescents themselves.

I’ve talked before about the “mismatch” model, which looks at the relationship between the development of the brain’s frontal lobes, which stop you taking risks, and the limbic system, which gives you a kick out of taking risks.

That model proposes that the limbic system is overactive in adolescence and the prefrontal cortex is not yet fully mature, and that’s the physiological explanation for why adolescents have an increased propensity to take risks.

That model is still very prevalent but has also been critiqued as being too simplistic, so more refined models have been proposed that include things such as emotions, social influence and individual differences.

So, what should teachers know about adolescent risk taking?

There’s quite a lot of data to show that when adolescents are on their own and not with their friends, they don’t necessarily take more risks than adults do. There’s something about the social context that increases risk taking.

The way we think about this now is that it isn’t that adolescents are necessarily increased risk takers. In fact, they might even be risk averse when it comes to taking social risks - that is, the risk of being socially excluded. They avoid taking social risks, even if that means they end up taking health or legal risks.

‘Most interventions, most curricula, most campaigns are designed by and led by adults. That’s missing a trick’

But most public health advertising aimed at teenagers focuses on the risk, saying you shouldn’t smoke because it’s really dangerous, or you shouldn’t drive fast in the car because it could cause an accident. But they know that; adolescents aren’t stupid.

Instead, there should be more focus on peer influence and how to have the self confidence to resist it in situations that you know carry health or legal risks.

How can this understanding be applied in schools?

We know that peer-led interventions in schools - anti-bullying interventions, for example, or anti-smoking interventions - work better than the same kinds of interventions led by teachers, which isn’t surprising when you consider that young people have a huge influence over each other.

But peer-led programmes are rarely used in schools. Most interventions, most curricula, most campaigns are designed by and led by adults. That’s missing a trick and not capitalising on what we know about adolescents’ propensity to influence each other to make good decisions and positive choices.

How about social media? What role does that play in influencing teenage behaviour?

Social media is complex. People want to make a very simplistic link between increased social media use in the past 10 or 15 years and an increase in mental health problems over the same period. Those two things are true, but that’s a correlation; we don’t know about causality. We do know that there seems to be a relationship between those two things for some young people but it’s bidirectional.

Of the young people who use social media more, some of them will have a negative impact from that, and other teenagers who may have mental health problems, such as depression, may be more likely to use social media. So, it goes in both directions.

We have found that it depends what age and gender people are. There seem to be periods of vulnerability in early adolescence - around the age of puberty - and again at age 19, when increased social media use does lead to poorer mental health for some young people.

It also depends on what people are looking at because there can be lots of positives about social media. However, I don’t think there’s any question around whether an 11-year-old benefits from seeing pornography, and many children in this country have seen pornography on a phone, a lot of which is violent and graphic.

I don’t see any argument that this could be a good thing for a developing young brain and mind.

Do you think there should be more restrictions on what young people can view online, like those proposed in the government’s Online Safety Bill, which is currently making its way through the House of Lords?

As I mentioned, I think the default should be that pornography is restricted, and it shouldn’t be viewable at all by children, because it’s not beneficial and could be quite harmful. It’s the same for other potentially harmful sites like self harm, suicide and anorexia sites.

There’s a lot of exposure to pernicious content, including by social media influencers with huge followings, that preys on vulnerable young people who are developing their sense of self-identity and don’t really know who they are. They have all sorts of worries in their heads, and these influencers give them a feeling of belonging and identity, but actually can be harmful.

Do you think that banning mobile phones in schools would help?

I’ve been asked if phones should be banned under a certain age but that doesn’t really make sense to me. There’s no good evidence for that, and there are lots of benefits of having a smartphone.

But there are sites that I think should be banned or age-restricted, and it’s possible to do this.

It’s clear that for some young people, interacting on phones feels like the easier option [than speaking to people face-to-face]. Covid and lockdowns had a big role to play in setting up that dynamic. It’s difficult to persuade young people to get off their phones because it became the only thing they could do during lockdown. It’s difficult to try to pedal back on that now.

It’s understandable that [being on your phone] feels less risky than going out and seeing people in person. You can just sit in your room, where you feel safe, and look at all this stuff online. But it’s not good, from what we know about the need for social interaction for brain development.

And it’s not even necessarily social interaction online - it’s often passively viewing what other people are up to, looking at TikTok and so on. And that’s taking a lot of time away that could be spent on other activities, such as sport and real social interaction, which is so crucial during that period of life.

What do we know about the effects of isolation on young people?

We know that social exclusion and loneliness are risk factors for mental health problems. It’s not a good state to be in. There’s research on animals showing that social isolation during adolescence has a more damaging effect on the brain and mental health than the same isolation either before puberty or in adulthood.

We’ve just finished a study looking at the effects of social isolation on adolescent behaviour. Previous studies have mostly been on mice and rats rather than humans because you can’t isolate a human for their whole adolescence. But you can do it for a short burst because that won’t have any long-term consequences.

We looked at what happens to 16- to 19-year-olds over a period of four hours in a room alone with no phone, no access to the internet, no social anything. No books, no TV with people and no windows. But they had everything else: food, a bathroom, puzzles that don’t have people in, Tetris-type games. And they could bring stuff to do as long as it didn’t include people, so they could bring maths homework, for example.

And then in another session, the same individuals were in the same room with nothing social except they could bring their phone, so that’s the social media control condition. And then we had a condition where they weren’t socially isolated at all.

‘I’ve been asked if phones should be banned under a certain age but that doesn’t really make sense to me’

We’re just finishing analysing the data at the moment but what we found is that, as in previous animal studies, social isolation makes young people more reward seeking. They will exert more effort to get a reward - a monetary reward or a social reward, such as seeing social photographs - and they are also more responsive to social feedback during learning tasks.

The social media session reduced some of those effects, which I suppose isn’t surprising because social media is social contact, but it didn’t completely remediate them.

We know it’s not necessarily good to be more reward-seeking; in the animal literature, that is tied up with seeking rewards like drug rewards. We didn’t look at that in our study, but we can say that being more reward-seeking is not necessarily a good state to be in.

What are the repercussions of that for schools?

Social isolation has always been used in schools as a punishment but, actually, such punishments might have counterproductive effects. Because socially isolating young people can then make them go into a state of higher reward seeking and seeking out social rewards.

Do you find that the education sector is receptive to your findings about the developing brain?

There’s a lot of enthusiasm about neuroscience and cognitive psychology data and evidence; all the policymakers I speak to are really interested in it. Whether it actually makes it into schools is a different question.

One real problem is that people are often looking for quick fixes or easy things to implement based on neuroscience, but it doesn’t really work like that. Neuroscience research is quite a long way from what happens in a classroom. And to make changes that would be beneficial to young people would probably mean restructuring the entire assessment system.

I was a member of the Times Education Commission and we recommended 15-year changes, but the problem is that governments don’t work in 15-year timescales - they work in less than five-year electoral timescales. And it’s difficult to envisage how you could change the whole assessment system in less than five years. So, there’s a lot of interest but there’s not much action.

What could an overhauled assessment system look like?

In my view, the GCSE system is outdated and unnecessary now that young people have to stay in school or some form of training until 18. And GCSEs aren’t really in keeping with what we know about the developing brain and the developing mind, and how adolescence is a period of increased creativity and exploration. Do we really need to cram young people’s minds with loads and loads of facts that they retain in the short term for their exams and, two weeks later, the information is lost?

GCSEs were originally brought in as O-Levels when most of the population left school at 16 and needed some kind of leaving certificate. Now that’s not the case. When 100 per cent of young people stay on, they don’t need a certificate at 16. No other country where children have to stay in school until 18 has high-stakes national exams at 16. They might have some form of school exam at 16 but not the same as the GCSE.

Of course, there is the question of what the replacement should be. You need some breadth, and A levels are too narrow, as many people have argued. It doesn’t make sense to force young people to narrow their choices down so much at such a young age when many have no idea what they want to do, and when we know that the brain continues to develop throughout adolescence into the mid or late twenties. So, perhaps that really needs to be replaced with some kind of baccalaureate system.

But those kinds of changes would take years to implement, so at the moment, we’re stuck.

Zofia Niemtus is a freelance writer

For the latest research, pedagogy and practical classroom advice delivered directly to your inbox every week, sign up to our Teaching Essentials newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article