Consider the following: where did the pupils in your class spend the first months of their lives? And how do they deal with stress?

Initially, these two questions appear completely unrelated. But, according to research published by Sam Wass, a professor of early years at the University of East London’s Baby Development Lab, there is a correlation between where children were raised at an early age and how they react to stressful situations.

In research published recently, Wass and his colleagues found that children who were born and raised in the city at an early age tend to be “high-stress” children, while those born and raised in the country tend to be “low-stress”.

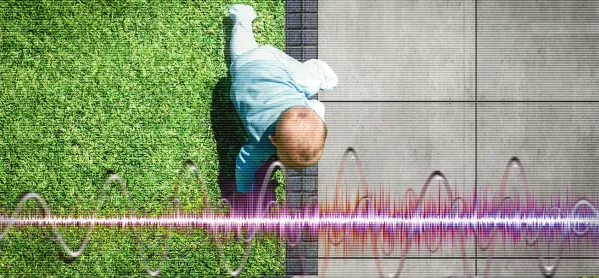

In this week’s episode of Tes Podagogy, Wass explains the research and its implications for early years foundation stage teachers and settings.

The research, he says, was driven by a global shift to where we live: 200 years ago, just 5 per cent of children were born in cities. Today, it’s over 50 per cent, and by 2050, it will be 70 per cent.

Wass explains that while research exists that shows the implications of city living on adults and older children - physical health outcomes tend to be better for those who live in the city, but mental health outcomes are worse - there is little research on how it affects infants.

Wass’ research is, then, the first of its kind, and it compared two groups of 12-month-olds - one group who lived in East London, and another who lived in Cambridge. Sensors were integrated into clothes the children were wearing, which monitored their heartbeat, their stress levels and their movement throughout the day.

The city children, Wass explains, showed higher levels of physiological stress - ie, they exhibited behaviours that were “flight or fight” throughout the day. They were worse at paying attention to one thing for a sustained period of time, and they got upset more quickly.

“They weren’t worse at everything, there were some things that they were actually better at,” adds Wass. “When we looked at their ability to learn rapid sequences of information, we found that high-stress city babies are actually better at it.

“We also found that they were engaging their brains more when they were paying attention to something, even though they weren’t paying attention to it for such a long period of time.”

In contrast, those children who were born in the country, had lower levels of physiological stress, were calmer, and “flatter” during the course of the day, and were better able to sustain their attention. However, the research also found that these children were more likely to “mind-wander”: where they may appear to be paying attention, when, actually, they are daydreaming.

“If you’re someone who works a lot with these more relaxed, rural-dwelling children, you may have this idea that the child is getting good marks on how they’re behaving in class because they’re sitting and staring right at [you],” Wass says. “But it’s very, very hard to tell, as a teacher, are they actually paying attention or not?”

Listen to more Podagogy:

Where you are born is not an absolute determiner for how you deal with stress, though, says Wass - there are variations.

“It’s about how you define stress, it’s changes to an environment, it’s properly defined as a short-term stress state. If a country kid is in a situation where they have to adapt, then they will be in a high-stress state, just as a city kid would be. It’s just that, overall, it seems that this is happening more often to city than to country children,” he explains.

So what does this research mean in practice? And should EYFS provision be adjusted to suit the differing needs of high-stress or low-stress children?

In the podcast, Wass answers these questions and more.