The cold, hard logic for increasing teacher pay

The chancellor, Rishi Sunak, is in the middle of considering the many competing bids aiming to secure funding in the government spending review this autumn, and charting the course of government spending over the next three years.

Teachers have a strong case for arguing that a series of highly competitive pay offers needs to form a key part of those spending plans. To achieve this end, the sector needs to make the case with vigour and a united voice.

However, this approach should be about logic - not emotions.

Of course, teachers and their representatives may be tempted to make an emotional case for a pay rise. The view that teachers have had a tough time in the pandemic and deserve a pay rise for their hard work and dedication to young people is comforting - and true.

But such a case may not be the most productive one when negotiating with the Treasury.

Instead, the case for improved teacher pay must be built around the risks of inaction to teacher supply and the negative consequences for young people and, in turn, the future prosperity of the country if the ongoing teacher recruitment issues are not addressed.

This may not seem the right time to use this argument, as the recent narrative on teacher supply has been a positive one about the impact of the economic paralysis induced by the pandemic on recruitment and retention across the workforce having a benefit on education.

After all, more teachers stayed in their jobs and graduates applied in record numbers for the chance to train as teachers - seeing it as a steady career opportunity in a world where nothing about the future felt very certain.

Why the case for teacher pay rises needs to be made now

Given this then, why is there a need to push hard for pay rises for teachers, especially those entering the profession as new teachers?

In short, because just as the spending review gets underway, the teacher supply ground has shifted dramatically once again.

The wider labour market has come roaring back to life, more quickly than anyone expected. In spring, economic forecasters thought the labour market might not return to normal until around 2024.

But now they think it is already back: vacancies in the economy are higher now than they were before the pandemic.

And there are signs in the recruitment data that applications to teacher training have dropped off as a result.

Moving in the wrong direction

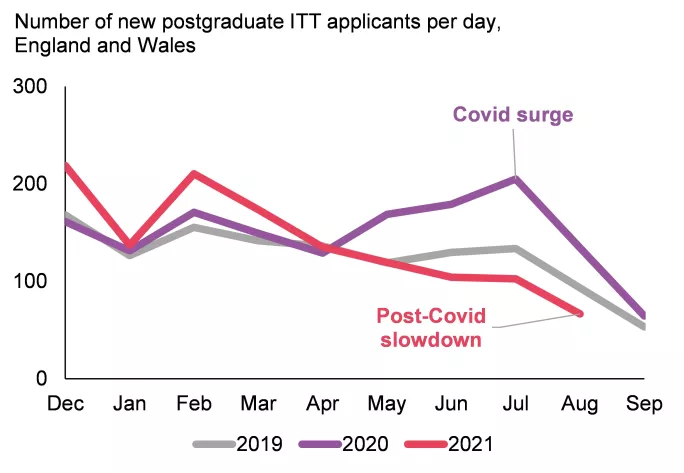

This summer, the rate of new applications fell below even the pre-pandemic years (see the chart below). What’s more, some of these applicants may not start their course if they have found another career option that they prefer in the meantime.

This situation continuing next year without any remedial action risks taking us back to square one, or even worse, on the issue of teacher training, recruitment and retention.

It therefore renews the case for funding to be allocated to addressing teacher supply issues before a substantial challenge occurs.

A quick fix should include the resumption of short-term measures such as bursaries in at-risk subjects such as English, biology and geography, where our modelling suggests they may dip below their recruitment targets this year by 5, 20 and even 30 per cent respectively.

More broadly, though, it should also include the revival of the longer-term plan to put teacher salaries on a more competitive footing compared with other professions.

In particular, especially as the state of the public finances is likely to constrain how much money can be allocated to teacher pay, the plan to raise the teacher starting salary more quickly than higher points on the pay scale should be prioritised.

NFER analysis of UCAS data

This situation is one that no one can claim not to have seen coming. After all, the competitiveness of teachers’ pay steadily declined in the past decade due to austerity, and undoubtedly contributed, at least in part, to challenges with teacher recruitment and retention.

That lack of competitiveness leaves the attractiveness of teaching in a weak position to respond to the rest of the labour market bouncing back - potentially making the situation even worse.

The risks this poses was summed up bluntly by the School Teachers’ Review Body when it declared in July in no uncertain terms that “a pay pause for teachers of more than one year risks a severe negative impact on the competitive position of the teaching profession, jeopardising efforts to attract and retain the high-quality graduates necessary to deliver improved pupil outcomes”.

All this underlines why the case for increased teacher pay needs to be made strongly to government - and made quickly.

This can certainly be done - by framing it around the government’s own priorities for the spending review that would justify why increasing pay for teachers will benefit not just teachers that have worked above and beyond during a pandemic but the long-term good of the country.

1. Teacher supply is fundamental for delivering strong public services

Attracting and retaining enough high-quality teachers in schools is essential for the healthy functioning of the education system, just as having enough doctors and nurses is crucial for the NHS to function.

The re-emergence of teacher supply challenges risks holding back the education sector’s ability to improve outcomes for young people.

2. Teacher supply is key to Covid recovery and ‘building back better’

The government’s response to the resignation of education recovery commissioner Sir Kevan Collins after the initial rejection of his proposals for Covid recovery was to defer decision making on some of the bigger-ticket items (eg, the extended school day) to the spending review.

This means that the claim for improved teacher pay is being considered alongside other bids for funding Covid recovery strategies.

There may be a temptation in the Treasury to view these bids as competitors for scarce funding.

However, adequate teacher supply is a necessary condition for a recovery strategy to be effective. Luke Sibieta argues that extending the school day will be most effective where it “draws on existing and well-trained staff” and is “integrated to existing classes and activities”.

The pandemic has not made teachers’ high workloads go away, so asking for more input from the existing teacher workforce risks the recovery effort failing, as well as compounding teacher supply issues by leading to higher attrition.

3. Teacher supply is essential for ‘levelling up’

If teacher supply issues take hold once again, the impact will be felt the greatest by schools in the most deprived areas. Research shows these schools struggle more to recruit and retain staff, which means they lose out the most when national supply dries up.

Teacher supply is key to the levelling up agenda as it is an essential component of ensuring that children from disadvantaged areas and family backgrounds have access to a high-quality education and are enabled to gain skills and flourish.

4. Teacher supply is critical for future economic growth

The government has ambitions for improving economic growth, fuelled by investment in science and technology.

The schoolchildren of today are the workforce of tomorrow, so the supply of those skills may dwindle without young people being taught by specialist teachers in these important subjects.

If teacher supply were to become problematic again, it is the Stem subjects such as physics, chemistry and mathematics that would suffer first and foremost.

Revisiting the introduction of specific policy measures to target improvements in Stem teacher recruitment and retention - such as the trialled-but-then-abolished system of early-career payments - needs to be part of the strategy for ensuring future teacher supply across all subjects.

In summary, the government needs to allocate the necessary funding to improve the competitiveness of teachers’ pay and shore up teacher supply, which is currently faltering once again.

The sector needs to make this case strongly now, and frame it in the government’s own terms - that way it may actually sit up, take notice and act. It would be no less than the sector deserves.

Jack Worth is lead economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER).

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

topics in this article