- Home

- ‘The fact is, teaching is just a difficult thing to judge’

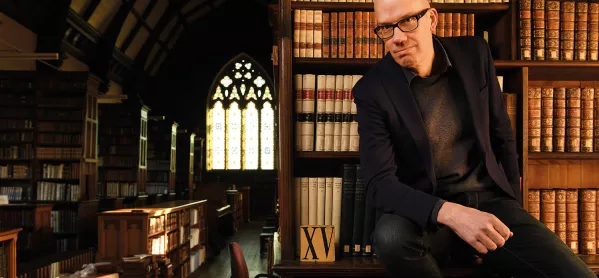

‘The fact is, teaching is just a difficult thing to judge’

You’ve been asked to formally observe a lesson in Year 9. The room is calm and the pupils are working hard, filling up their pages with notes.

When the teacher asks a question, lots of hands shoot up to volunteer answers. The responses are correct and detailed, and students go back to their work quickly and with evident enthusiasm.

How would you rate this lesson? If you had to judge how much learning was taking place, what would you say?

Well, you are in no position to make an assessment, according to Rob Coe, because you simply cannot answer those questions based on the indicators listed above. Nothing described there is linked to the amount of learning taking place, he explains. Instead, what you can see are a series of “weak proxies for learning”.

“They’re not bad things and they may help to indicate learning, but they’re not great indicators because you can have all those things happening and no learning at all,” he says. “You don’t know, for example, if they’re just rehearsing stuff they already knew how to do. That’s really common in a lot of classrooms: kids are just asked to do things they can already do. And there’s a kind of complicity between the students and the teachers; it suits everyone to do that because it’s not too challenging. It happens a lot, but if you’re an observer, how would you know?”

Creating systems

Coe used to be a secondary maths teacher before going on to study for his PhD at Durham University. He is now a professor in the School of Education there, and director of the university’s renowned Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring (CEM), which creates assessments and monitoring systems for students across the world. It was back in 2014 in his CEM role that he found himself accidentally waging war against lesson observation.

He began looking into the latest studies on teacher assessment and speaking to researchers exploring the subject. He published some initial thoughts on the CEM blog under the headline “Classroom observation: it’s harder than you think”, and started a heated discussion on the subject. “I did some simulations and wrote some things about it and caught a wave, I think, because a lot of people were also unhappy and ready to try to move away from those practices,” he says.

In the blog, he talks about his response to attending a ResearchEd conference and hearing references to the formerly popular “fashions” of Brain Gym, VAK learning styles, left/right brain dominance, and the rest. “I sensed a hint of smugness among the delegates,” he writes. “They had never embraced such flakiness, or if they had it was short-lived and emphatically renounced. I couldn’t resist trying to challenge any feelings of being ‘holier than thou’ by pointing out something they were still doing, but for which evidential justification was no better than the flaky stuff: classroom observation.”

Despite its omnipresence in schools of all shapes and sizes, evidence about the effectiveness of observations is not good. At all.

Coe cites the work of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Measures of Effective Teaching project, which found that the likelihood of two observers offering different ratings on the same lesson was between 51 per cent and 78 per cent. He also draws attention to a 2011 study, which found that 63 per cent of judgements about effective teaching were wrong.

What you see isn’t what you get

The problem with the teacher assessment system as it currently stands is that it’s hugely influenced by personal impressions, he says. When you’re observing in a classroom, you will have a strong sense of whether you like what you see, but that often isn’t linked to the effectiveness of the teacher.

“If you assess children and look at how much they actually learned, you find that the correlation between that and the judgements people actually make about the teacher are pretty weak; it just doesn’t predict it,” he says.

There’s an important distinction to be drawn between the visible and less visible elements of teaching, he continues, but this often gets overlooked.

Things such as organisation and resource preparation (both of which he admits he “wasn’t great at” during his own classroom career) are highly visible, along with general classroom and behaviour management.

“Behaviour is one aspect of teaching that is very visible,” he says. “You can’t really hide. If you’re not on top of it: you know, the kids know and anyone who comes to observe knows. And it is a barrier to effective teaching. A lot of teachers can manage those things, but they’re still not very good at the other aspects, like being able to activate children’s thinking in productive ways, which is a really hard thing to do. It’s much less visible. How can you tell if children are thinking or not?”

And so mistakes are being made. Teachers who are good at the visible parts of classroom management, but not at getting their classes to think, may be incorrectly applauded because their classrooms appear orderly and purposeful. Conversely, teachers who excel at the invisible elements of inspiring learning, but struggle with the visible, could be wrongly labelled as ineffective.

The fact is, teaching is just a difficult thing to judge, says Coe.

“It’s hard to say whether children are learning or not, or thinking in the right sorts of ways,” he explains. “It’s a slow process; it goes forward and back, not forward steadily.”

Of course, improvements have been made in the general acknowledgement of the limits of lesson observation. The idea that a single observation is insufficient to make a judgement about a teacher’s effectiveness has been gaining momentum for some time.

Ofsted has stopped grading individual lessons and the fact that some schools still use the practice is a well-reported source of frustration for the inspectorate, with chief inspector Amanda Spielman claiming that she “tears her hair out” over it. But things are still far from ideal, says Coe.

“There have been changes, but it’s still a pretty amateurish business,” he continues. “Ofsted may not make individual gradings for lessons any more, but the processes they use [to judge teaching and learning] are not in line with the best evidence.”

Coe is careful to point out that he isn’t against observations altogether, but thinks they need a serious overhaul to be of real worth. So what would that look like? For starters, he argues we should rethink who gets to carry them out.

“Why not choose the teachers who are the best at teaching, rather than the senior management team?” says Coe. “It’s likely that a person who can teach well themselves is less likely to be distracted by the fads and wrong turns that people advocate as being effective practice. There’s less risk that they’ll make the wrong judgements and give the wrong advice.”

But even this isn’t fail-safe, he continues. Experienced teachers may well have “automated” their behaviour, meaning that when they see others teaching well, they might not be able to explain what it is about their practice that is effective. So Coe proposes an obvious source of insight that could be tapped for information: students.

‘Ofsted is keen to learn’

He acknowledges that the process would need to be managed properly to avoid turning it into a popularity contest. “Like anything, if you do it badly, you can do more harm than good,” he says. Despite this risk, students have a thorough understanding of what is taking place in lessons, what is working and what isn’t, and schools could be making better use of their perspective.

But in the end, he says, the best way to assess teacher effectiveness is the slowest and most obvious: looking at students’ results.

“You look at who is making progress on those assessments and you start to understand what impact the teacher is having,” he explains. “When you look at those over a period of time, you’ll see that there are some teachers who consistently get the results every year. You have to be cautious about overinterpreting that because whether children learn something or not isn’t just down to the teacher, it’s also about the kids and there are a lot of other variables in there. But when you see a consistent pattern, that’s definitely telling you something.”

And in the meantime, he is hoping that the ongoing conversation about improving teacher assessment will make Ofsted more effective, and that changes will trickle down into schools.

“Ofsted is now keen to learn about good practice in this area. It’s a conversation that I and some others are having with it about how it can improve what it does, to bring it in line with the evidence,” he says.

“That’s really welcome.”

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter, and like Tes on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters