- Home

- GCSE Results Day: How does Progress 8 work?

GCSE Results Day: How does Progress 8 work?

Progress 8 is heralded as the measure that will ensure the attainment of all students is prioritised at GCSE, not just those on the C/D borderline. But is the new system any better - and any fairer - than the one it replaced

Emily had never been on a list of students in need of urgent academic assistance before. And if she had been born a year earlier, she would probably have left school without ever having been on one.

She is quiet and conscientious. She was revising well for her GCSEs and seemed confident. She was as safe a bet as there could be for a full house of good grades. Last year, no one on the senior leadership team would have been worried about Emily. They would have been busy elsewhere, frantically rounding up C/D borderline students for revision classes, offering them one-to-one support, giving them every permutation of question and scenario that a brain trust of experienced teachers could come up with.

But this year, Emily found herself on the list. This year, her school will not be judged on 5 A*-Cs, but rather the progress of students. This year is the second year of Progress 8.

There are thousands of students like Emily across England that will have been abruptly introduced to the world of school accountability this year. And if you believe former education secretary Nicky Morgan, it is for their own good.

Referring to the introduction of the new Progress 8 measure in a speech in January 2015, she said: “No longer will it be the case that the only pupils that matter will be those on the C/D borderline. Instead, those schools that will be rewarded are those that push each pupil to reach their potential.”

Fantastic news for schools, you might think: they push every child to succeed already so, finally, they will be getting some credit for it. Could it really be that simple?

When you begin to look closely at Progress 8, you find it to be a very tangled web indeed. And those that have begun to unpick it are starting to ask whether this system is really any better - any fairer to students and schools - than the one it has replaced.

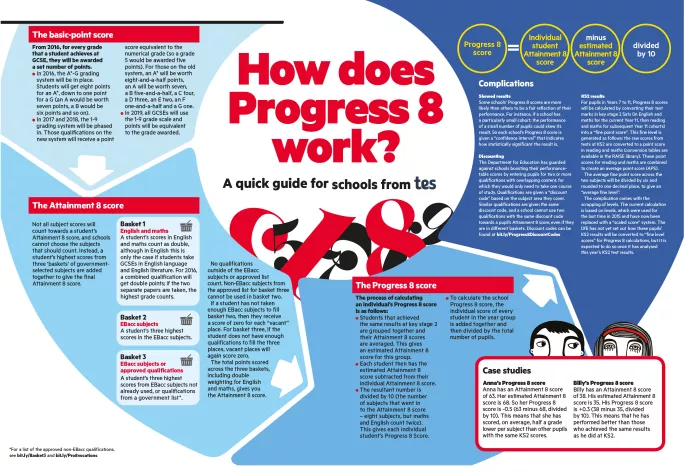

Progress 8 measures schools not just on the results that pupils achieve, but on how much progress they have made since they started secondary school.

“So high attainers that come in with pretty high grades from primary school [now] need to get particularly high grades to ensure they have a positive Progress 8 score,” says John Stanier, assistant headteacher at Great Torrington School in Devon.

“These children have had As and Bs through their whole school career and suddenly they’re being told they’ve got a negative score and we need to intervene with them, because they’re not making the grade. A lot of teachers have found it difficult, and it has caused upset to some children because they’d never had the experience of being told, ‘Your progress isn’t where it should be’.

“But a bit of me doesn’t think that’s a bad thing, because the emphasis has been placed on the C/D borderline pupils for so long.”

The previous headline measure of five good GCSE grades led to schools targeting disproportionate resources - the best teachers, the best tools and extra interventions - at pupils on the cusp of scoring a C grade.

Critics said this meant that the most able pupils were not being stretched and those who needed the most support were missing out. “Progress 8 is designed to stop schools relentlessly targeting a small number of kids on the borderline,” says Nigel Matthias, deputy headteacher of Bay House School in Hampshire.

The old measure also gave an advantage to selective schools and those in affluent areas. The new measure should mean that will no longer be the case.

So the majority of schools should, in theory, be jubilant. And many, sort of, are. But there is some trepidation, too.

The first reason that schools are not throwing a street party in celebration of Progress 8 is that they’re too busy trying to work out quite how the new measure is to be calculated.

As soon as you start to break the metric down to its component parts you find yourself in some form of perverse orientation exercise. You could write pages of explanation about how to find your way out again (we’ve made it easier by detailing everything you need to know on a single poster, attached to this feature).

The second reason for some schools’ unease is that last September’s new Year 7s were expected to be a complicated year group. The long-standing system of levels at key stage 2 was replaced with new assessments that give 11-year-olds a “scaled score” on which 100 will represent the “national standard”.

These changes have “chucked a hand grenade” into Progress 8, says James Pembroke, a data analyst at the school data firm Sig+ and a Tes columnist. Schools know that they will be judged on their ability to get the new intake to progress from their KS2 results, but they will find it difficult to judge what, exactly, progress would look like (see our Progress 8 poster above for additional complications around KS2 results).

“Schools will get children in September and think, what do I do with these results?” says Pembroke. “I’ve spoken to people at secondary schools in the past year who have looked blankly at me when I said they’d get a scaled score and said, ‘You’ll still get a level as well though, right?’

“We will be in a situation where some secondary schools will try to convert key stage 2 data into a level, then convert the end point into an old letter-grade GCSE [to understand how much progress the pupil is expected to make]. They’ll be doing all this spurious conversion stuff.”

“We won’t know how much better a score of 102 is than 101, and what that really means,” admits Peter Atherton, a school data manager based in Wakefield and author of the Data Educator blog.

“We won’t know what it equates to in a Progress 8 estimate until five years later when pupils have done their GCSEs. So it will be difficult to know whether you’ve set pupils appropriately,” he says.

This uncertainty will be reflected in schools’ results, according to Simon Burgess, an academic who helped to devise Progress 8. “Clearly there’s a lot of upheaval,” says Burgess, an economics professor at the University of Bristol. “Some schools are going to get wildly unusual scores on Progress 8.”

For the heads whose careers rest on the measure, Burgess’ verdict will not exactly be a comfort. But in reality it will join rather a long list of concerns that they have already. Beyond the above issues, Progress 8 has provoked a range of ideological and practical concerns.

The most common of these is the charge that Progress 8 has narrowed pupils’ curriculum choices by forcing schools to make sure children take traditional academic GCSEs over creative subjects. Because Progress 8 scores are determined by certain subjects only - which have been put into three “buckets” - schools are forced to prioritise those (predominantly English Baccalaureate subjects) over others.

“When you have conversations about option choices with children it has been about making sure the Progress 8 buckets are filled first before you start talking about subjects like drama and music,” says Stanier. “You feel that the culture is shifting, which is a real shame.”

There are exceptions to this: David Taylor, headteacher at Stanley Park High School in Sutton, says that his school is continuing to offer subjects such as a BTEC in horticulture that “count for the kids but not for the school”. But, he says with a nervous laugh, it will be “interesting to see what happens” if this causes the school to score badly on Progress 8.

Another big concern about Progress 8 is that it might replicate the failing of previous accountability measures by giving schools with high-ability intakes an advantage.

Research by Education Datalab, published in March last year, found that schools with large numbers of lower ability pupils would be disproportionately penalised - even though the measure was designed to avoid this.

Education Datalab’s director, Dr Becky Allen, who wrote the report, says that if lower scores for schools with lower-ability intakes have come about because pupils at schools in affluent areas have a supportive home environment that causes them to make more progress, then Progress 8 “would seem unfair to schools serving disadvantaged communities”.

However she adds that if schools in disadvantaged areas are less effective than others - because they find it harder to recruit and retain teachers and school leaders, for instance - then Progress 8 could be a reasonable measure of school performance. Deciding which of these scenarios is in play is a task that should not be taken lightly, she says. “It’s really important that Ofsted inspectors understand the social gradient, rather than saying to schools, it [your score] is negative, so there’s a problem.”

‘Low expectations’

Burgess admits that there is some truth in the criticism. He explains that the Department for Education insisted that progress should be defined in relation only to key stage 2 results and should not “differentiate by social class, household income, gender or ethnicity.”

This is perhaps unsurprising, given concerns often expressed by DfE ministers that setting different standards for schools and pupils in disadvantaged areas amounts to the “soft bigotry of low expectations”.

But Burgess says it will affect schools’ scores. “There are known to be factors other than prior attainment that influence GCSE outcomes,” he says. “By not taking those into account, and only conditioning on prior attainment, some pupils will be more likely to achieve below their expected level. By extension, schools with a disproportionate number of those pupils will also be more likely to produce a score below that expected.”

There’s a second reason that schools with higher-ability intakes might benefit more from Progress 8 than others. As the new GCSEs, graded from 9 to 1, are introduced, the calculation of Progress 8 will change.

The new scores will be phased in from 2017. For those qualifications that have shifted to the new system, the number of Attainment 8 points (which go into the calculation to determine Progress 8 - see poster) will be equivalent to the grade, so a top grade 9 will be worth 9 points, and so on. But the remaining unreformed GCSEs will attract Attainment 8 points using a new scale.

An A* will be worth eight-and-a-half points (this year it is worth eight points), an A will be worth seven, a B five-and-a-half, a C four, a D three, an E two, an F one-and-a-half and a G one.

This scale has prompted concern that schools are being given an incentive to focus on their high-attaining pupils, because raising an A-grade pupil to an A* attracts more points (1.5) than raising a G-grade pupil to an F (0.5).

Stanier says that his school had “bought in” to the idea of Progress 8 but is now “frustrated” about this discrepancy.

“We liked Progress 8 because it meant that every child’s grades mattered, but now that the government has [changed] the points it means schools will focus more at the top end than the bottom end, because that’s where the points are. So children at the bottom end could be penalised,” he says.

Allen says that this change will be “really tough” because it will lead to a “fall in results for schools with lower-attaining intakes”. But she adds that it was “never particularly right to have a one-point difference between each grade”.

“Everybody agrees that it’s easier to get a child from an F to an E than a B to an A,” she says. “The return on 10 hours’ investment with a child likely to get a G is likely to move them up, whereas 10 hours with someone likely to get a B might not get them an A.”

Because of this, she says, schools trying to boost their results in 2016, when all grade rises are worth the same (one point), should focus on their lower-attaining pupils. “To get a whole point to move someone from a G to an E, given it’s pretty easy, makes it a worthwhile thing to do,” she says.

To do so, of course, would be to make a mockery of Morgan’s pledge that Progress 8 would ensure all students would be focused on equally. But Burgess says that her aim may have been flawed from the start. He argues that schools could live to regret shifting their focus away from the C/D borderline pupils as a result of Progress 8.

“Maybe this is quite a useful group of students to focus on,” he says. “When we remove that, it’s very hard to focus on everyone, so schools will focus somewhere or other. Maybe in future we’ll regret the idea that we abolished a system that encouraged schools to focus on kids in the middle of the distribution as opposed to those at the top.”

Allen is supportive of this view. The DfE has said that students will have to retake English and maths if they don’t get a grade 5 from 2020. For 2018 and 2019, the retakes will be mandatory for those who don’t hit a grade 4. Meanwhile, businesses are likely to ask for a grade 4 or 5 as a minimum requirement. So, she says, you could argue that a focus on these students still makes sense for schools.

“There’s an argument that if you’re going to force people to retake [exams] if they don’t get a C - then a grade 5 - then there’s something to be said for focusing on the people on the margin. The welfare returns of getting them across the boundary are really high.”

But, she says, the “counter-argument” is that schools should focus on lower-attaining pupils because “having a level of functional literacy and numeracy skills is so important.”

If all this were not enough, there’s a final problem with Progress 8 to consider, too: it does not lend itself to assisting schools in making, erm, progress.

Schools don’t expect to know how well they have performed on the measure until several months after results day, because they will have to wait for the DfE to publish data on the performance of pupils across the country. “Within the first half term of a new school year, heads of department have to write a report where they reflect on the previous year’s GCSE cohort and the course and put in place an action plan,” Stanier says.

“But this year there’ll be a hole in the data, and we’ll only be able to guesstimate how well we’ve done.

“By the time we get our Progress 8 data, we might only have half a year to make improvements and implement changes based on that data.”

A step in the right direction

So when schools assess Progress 8 properly, are they finding that, actually, it is not as welcome a change as they first thought? Certainly there are numerous problems that have been identified, but many heads and data experts see the shift towards a progress measure, in principle, as a step in the right direction. “I don’t think it’s a perfect tool but it’s a vast improvement on what came before it,” Matthias says. “It means the emphasis is on improving outcomes for all pupils.”

Atherton agrees: “It’s not been implemented as well as it could have been, but I do think it’s a better measure than what went before it.”

But just as they look forward to progress, in principle, becoming the new cornerstone of the accountability system, experts fear that a change in direction could be on the cards.

The proportion of pupils gaining a “good pass” in maths and English (a C this year, then a 5 from 2017) will be reported alongside the Progress 8 measure in school performance tables. Like its predecessor measure - the proportion gaining five good passes including English and maths - it will favour grammar schools and others with high-ability intakes. And it’s a lot easier to understand than a Progress 8 score.

“At the moment, half the profession is scratching their heads [about Progress 8], so I’m not sure what chance parents have got of understanding it,” says Taylor.

So while the government may wish for Progress 8 to be the marker of a “good” school, and despite schools broadly welcoming it, by what measure will the public make that call?

“I wonder, are we going to end up in a situation where the public ignores Progress 8 in the same way that they ignored value added [a previous measure of progress]?” says Allen. “We’re once again back with the attainment measures we were trying to get away from.”

Different approaches to comparing schools’ performance

In Scotland, secondary schools’ performance is compared using an online tool called Insight, which was introduced in 2014. Schools use the tool to understand how well they are serving different groups of pupils, such as girls, boys, children in care and children from the most-deprived and least-deprived areas. Schools can also see how well their pupils are doing compared to other pupils in similar circumstances in other parts of the country.

Members of the public can view data on leavers’ destinations and the attainment of pupils in the “senior phase”, from age 14 to 18. The attainment data is presented in the context of deprivation, using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority oversees the country’s National Assessment Program - Literacy and Numeracy (Naplan), which assesses students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 (aged nine, 11, 13 and 15). Australia’s My School website contains eight years of Naplan data and allows comparisons to be made between schools with students from similar socio-economic backgrounds using the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage. This takes into account students’ family backgrounds and parents’ occupations as well as the school’s location and its proportion of indigenous students. Schools’ results are shown next to average results for statistically similar schools, and for all Australian schools.

A report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development found that school accountability based on student test results “can be a powerful tool for changing teacher and school behaviour but it often creates unintended strategic behaviour”.

It said that aggregated national data on student test results were published in Australia, Canada, France, Iceland, Mexico, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, England and the United States. In Norway, however, results from the national student assessment were published only at a local and regional level, while in Germany and Spain, results were published only on the regional or state level, it said. The report also found that in Austria, Denmark, France, Ireland and parts of Belgium, official documents stated that national tests should not be used to rank schools.

“The available evidence regarding the effect of publishing student test results in school performance tables is mixed,” the report, published in 2010, found. “There is little evidence of a positive relationship between performance tables and increased student performance. There is, however, evidence of performance tables influencing the behaviour of schools, teachers and parents - although not always as originally intended by the authorities.”

Keep up to date with all the latest GCSE news, views and analysis on our GCSE hub.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles