- Home

- How to spot the signs of an eating disorder

How to spot the signs of an eating disorder

When I was 14 years old, I nearly died from anorexia nervosa.

I hid the early signs from my parents, but if my friends and teachers had known what to look out for, they might have noticed that something was wrong and been able to help me sooner.

Twelve years later, after lots of support from teachers, health professionals and family, I am pleased to say that I am recovered. I qualified as a doctor and I now work in a hospital in Bath.

But I didn’t forget about my experience with anorexia. That’s why I have worked with staff and pupils at my old school (The Romsey School in Hampshire) to develop a set of resources that will help to educate teachers and pupils from Years 7 to 10 on how to spot the early signs of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder – and, crucially, how to respond appropriately when they notice these signs.

Quick read: The flaws in how schools talk about food

Quick listen: The truth about mental health in schools

Want to know more: Tes talks to the stars of the Instagram body-positivity movement

So what are the signs to look out for? I have used a simple "ABCDE" memory tool to describe some of the common behaviours that pupils with an eating disorder might exhibit.

Absence

Absenting themselves from food-related activities

- Anorexia nervosa: sufferers might find ways to avoid situations where they are expected to eat with other people, especially when the food is high in calories and/or they cannot control the type of food that is served (such as parties and visits to restaurants);

- Bulimia nervosa: they might go straight to the toilet after a meal, in order to vomit the food they have eaten or secretly use laxatives or exercise to compensate for the calorie intake;

- Binge-eating disorder: they typically binge secretly, away from other people and might avoid close relationships for fear of being humiliated.

Body

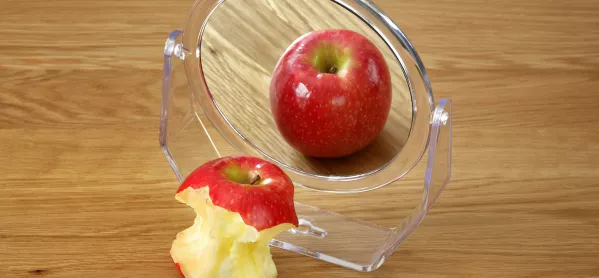

Obsessively worrying about the shape of their body

- Anorexia nervosa: sufferers might develop a distorted body image (technically called body dysmorphia) and become particularly sensitive to any real or imagined comments about body shape;

- Bulimia nervosa: sensitivity to their own thoughts or other people’s comments about body shape might lead them to use food to derive comfort but then feel compelled to remove the food through purging;

- Binge-eating disorder: binge eating without purging can lead to weight gain. Subsequent real or imagined comments about body shape can compound the feelings of shame, which, paradoxically, can lead to more binge eating as a means of seeking comfort in food.

Control

Compulsively in control, or out of control, of food

- Anorexia nervosa: to control their food intake, sufferers might find ways to pretend to have eaten what they have actually given or thrown away; and they might seek to control the content and timing of meals;

- Bulimia nervosa: they might feel unable to control the desire to eat and, having binged, try to take control over what happens to that food by purging it as quickly as possible;

- Binge-eating disorder: they might feel unable to control the overwhelming desire to binge repeatedly, feeling unable to stop eating even when excessively full.

Diet

Radically changing their diet

- Anorexia nervosa: sufferers might claim to no longer like food which they previously enjoyed, or might adopt restrictive food preferences such as clean eating or veganism without the corresponding belief systems;

- Bulimia nervosa: because of the drive to purge meals which they have eaten, they might develop a preference for food which is easy to purge;

- Binge-eating disorder: the compulsion to binge, and the associated shame, can lead to maintaining secret stores of food that can be accessed in private.

Exercise

Exercising excessively or obsessively

- Anorexia nervosa: sufferers might exercise to the point of exhaustion, and avoid food if they don’t think they have exercised sufficiently;

- Bulimia nervosa: the purge element of the binge-purge cycle might include exercise as well as, or instead of, the use of vomiting or laxatives. Thus, their exercise is related to the amount they binge, and driven by their food intake rather than a reasoned and reasonable exercise programme;

- Binge-eating disorder: exercise does not appear to be an indicator of this disorder since they might exercise normally, excessively or not at all.

Dr McNaught's resources consist of a ‘Spot The Signs’ film and a series of PSHE lessons, which are available for teachers to download for free online.

Dr Elizabeth McNaught is a doctor at a hospital in Bath and the medical director of Family Mental Wealth

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters