- Home

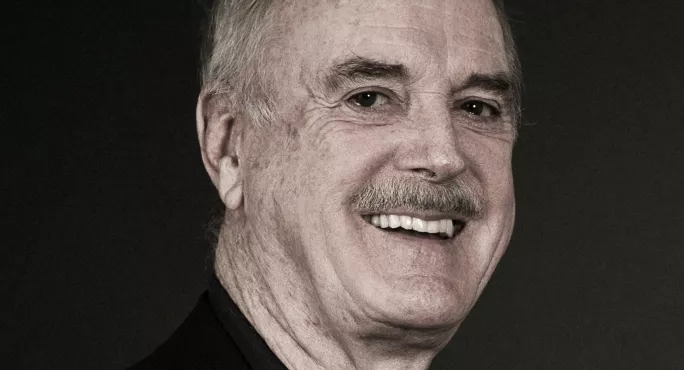

- John Cleese: Switch off smartphones for creativity

John Cleese: Switch off smartphones for creativity

The starting point is something that’s extraordinary, but that we take for granted: creativity isn’t taught in schools. In fact, I think most education systems actively discourage it.

When I was 15, I had to write an essay on “Time”. I wrote the whole piece about the fact that I didn’t have time to write it. Looking back, I think that was rather amusing, but the attitude of my teachers was: why haven’t you written a proper essay?

They were very nice, the teachers at my school, but I don’t think any of them were creative. So how were they going to recognise someone who was? It never occurred to me that I was the slightest bit creative.

Then, at the University of Cambridge, I discovered that I could take a blank sheet of paper and write something that made people laugh.

And I began to notice things about my new-found ability. Ever since, over 60 years, I’ve slowly assembled ideas that help to explain how it works.

Childlike play

The key idea is that anything really creative comes from the unconscious mind. In the 1970s, research at the University of California, at Berkeley showed that people with fine critical minds couldn’t have new ideas unless they know how to play. They found that what made people creative was, quite simply, the ability to play. They called this play “childlike”.

Then I discovered a new idea from a book called Homo Ludens: that play can only happen away from the pressures of ordinary life. The reason children can play so freely is that they don’t have to worry about responsibilities, because their parents are “minding the shop”.

However, adults can play, but only if they arrange a space in their schedules when they can forget about their usual responsibilities and just…sit and speculate.

So you can become more creative straight away if you arrange this space.

A chunk of time and a quiet space

We should teach children this principle in schools. It doesn’t take very long to teach people that you need a chunk of time and a quiet space. The hard thing as an adult is actually arranging it.

When you have arranged it, there’s a new thing to consider. For the first part of your quiet time, your mind is just chattering away: “I should have called Tom. Why was that man rude to me on the bus? Why do the Germans always win on penalties? I should have bought the cat a birthday present.”

And then, after a time - as in meditation - as your mind settles, you start to have ideas. These come as images or hunches or feelings: quite subtle things, which you’re never going to pick up if you’re racing around and checking your watch and taking every phone call.

It really is as simple as that. You just sit there.

And you just think.

Not particularly hard. Just letting the mind roam around the problem you’ve chosen. Pondering…

Being seen to be busy

Now, when you’re thinking, there’s no such thing as a mistake. If you’re having an idea, how do you know at the start if it’s going to be good or bad? It may lead anywhere.

But, when you’ve had a hunch, and you’ve explored it for some time, you need to evaluate it - to work out if it’s any good.

So then you switch back to your normal logical, critical, analytical frame of mind, and assess the idea. And you can then go back and forth between creative spells, and logical spells, as you refine the idea you first had.

The main snag is that people feel they need to be seen to be busy.

Samuel Goldwyn, when he ran MGM studios, used to visit the writers’ building to check if they were working hard. So the writers hired a lookout to tell them when Goldwyn was coming and then they’d put in a new sheet of paper in the typewriter and type any old rubbish very fast for three minutes. And Goldwyn would hear clattering, and think, oh, they’re working hard, and go back to his office. And the writers would throw the sheet away and go on with their thinking.

Whereas when Einstein used to sit in his office at Princeton with his feet on his desk, no one thought he wasn’t working.

So, if your boss doesn’t understand the nature of creativity, you’d better hide during your creative sessions.

These days, we live in an atmosphere that’s antithetical to creativity because it’s so hard to be still when you’re anxious, and impossible if you’re being interrupted by people or smartphones.

It was easier 40 years ago. Now it requires real planning.

Creativity: A short and cheerful guide, by John Cleese, is published by Hutchinson, £9.99

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters