- Home

- How Marcus Rashford can help inspire a kinder future

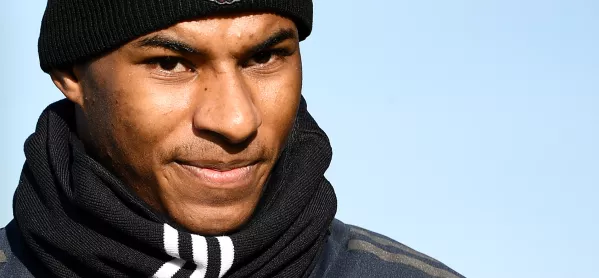

How Marcus Rashford can help inspire a kinder future

“Destroyed, no-platformed, toxic masculinity, ‘ok boomer’, cancel culture…”

If you haven’t yet noticed the ever-evolving vocabulary of accusation, you probably haven’t spent much time on social media.

This is a language of competition, demanding submission from a perceived opponent. And it’s about group identity - as people pit themselves against supposedly ‘other’ groups.

The driving force behind these fights overwhelmingly stems from people having experienced real injustice, real pain and a palpable sense that their voice is not being heard.

But, in a world where everyone is tweeting, texting, blogging, Instagramming and TikToking, being heard is rarely easy.

This can lead to something counterintuitive - a fight to come in last, to prove how victimised one’s group is.

Competitive victimhood

A 2017 paper from the European Journal of Social Psychology, names this process “competitive victimhood”. If our group can prove we are the victims, then we are innocent and “they” must be to blame. This gives our group moral superiority and allows us to shut down other voices.

But, while this may seem to be about empowerment, often it’s not.

Encouraging young people to compete to show how victimised they are comes with the serious risk of engendering learned helplessness, resentment and a fear of other groups.

Related to this is the danger that it focuses all our attention on the things that divide us.

Rather than starting from the expectation of building bridges, every interaction with someone from another group becomes a potential microaggression - something that gives us new evidence to weaponise our arguments and win the next fight.

Finally, it’s a competition, which means that winning is what really matters.

That means that truth is secondary, listening is not that important, trying to find common ground is much too complicated. Winning the war is all that matters.

Winning at all costs

But the thing about wars of any kind is that they are rarely “won” and they always cause untold damage along the way.

As teachers, we have a duty to help young people fight for justice and equality by educating them about injustice and ways to live in a pluralistic society.

But we need to do this in a way that limits the likelihood of their thinking that the best way forward is simply to gather evidence of group-based injustice - we must reduce the chance of them falling into resentment, despair and unfocused anger.

There are, of course, no easy solutions to this.

But I would like to suggest that we do not forget to shift the focus, even for a few moments each day, towards gratitude.

Gratitude rules, OK?

Gratitude moves us from division to connection because it forces all of us to think about the good things that we have received from those around us.

Working in an international school has helped me to focus on gratitude. I am deeply grateful to the local Malawians who befriended me and my family when we arrived, thousands of miles from home.

They were charitable enough to focus on our shared values rather than the many things that could have divided us.

And, when we return on visits to the UK, I am always humbled by the generosity of our friends and family who open their homes to us.

In schools, we should never stop highlighting and discussing injustice. But we should also never stop modelling our own appreciation for all the kindness we receive from others.

And we need to continue to think of effective ways to show young people who live in countries with access to education, sport, music, art, ideas and freedoms - that millions of people throughout history only dreamt of, and that millions of people living throughout the world still dream of - that these things are not a given.

Rashford’s inspiration

Some may see a focus on gratitude as an attempt to paper over inequalities and encourage complacency. But look at the recent campaign by Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford.

He mobilised more than 240,000 people, putting huge pressure on the UK government until it gave in to his demand that it reinstate the food voucher scheme for underprivileged children over the summer holiday period.

Now about 1.3 million children will get free school meals throughout the summer.

As Rashford campaigns, he consistently talks about how grateful he is for the sacrifices, love and kindness he received especially from his mother, but also his neighbours and coaches.

He’s aware of the help he has received and this is the basis of his drive to help others. It’s not about owning or cancelling - it’s about fighting for real change.

As he said himself: “Just look at what we can do when we come together.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters