Pictures really do tell a thousand words

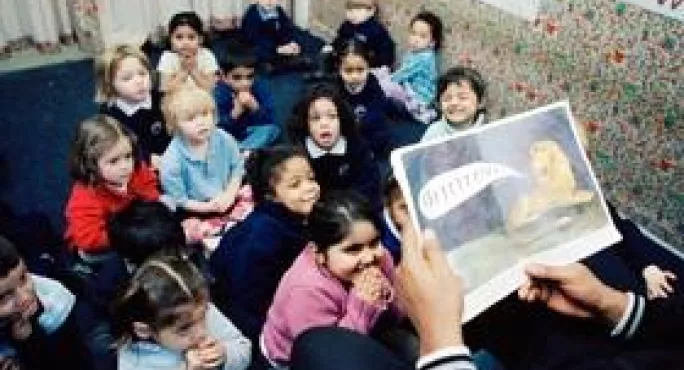

The most effective way to improve many children’s literacy is to ignore words and instead concentrate on picture books, according to award- winning research.

University of Glasgow researchers were originally seeking a strategy to help migrant children with poor English to settle into classrooms - but a study has revealed that the approach it came up with is also highly effective at boosting language skills among children who have English as their first language.

An 18-month project looking at using pictures as well as text in developing literacy found that even advanced readers could benefit from returning to almost wordless books.

Researchers built on previous studies by working with children at St Martha’s and Holy Cross primaries in Glasgow. The two classes of P6 students, which included refugees and asylum seekers but also native English speakers, started with picture books, before exploring pictures and text, and then moving on to text only. Work included putting picture books into words and producing artwork to illustrate texts without pictures.

The research found that these visual strategies “provided a level playing field for all students because there were no expectations about success or failure based on the traditional reading and writing skills”. Moreover, it says, children “expanded their communicative language competencies” as they described images and expressed ideas and feelings about a story.

This helped migrant children’s reading and made them more likely to discuss their experiences and culture, but Scottish children also benefited. The themes “resonated . for the `host’ children who had experienced sectarianism and family separations”, and helped to improve the work of Scottish children who had been struggling to read, the research team found.

Project leader Evelyn Arizpe said that the study had turned on its head the idea that children who cannot speak English are at a fundamental disadvantage in developing literacy skills and should be educated separately. “The visual literacy skills that the children already have can build their overall literacy, regardless of whether they are EAL (English as an additional language) children or English speakers. They have as much to contribute as other children - sometimes more, because they have to communicate a lot more when finding meaning in the visual,” she said.

Given the project’s success, and positive findings in other research, Dr Arizpe is concerned that picture books feature only in the Curriculum for Excellence for nursery and lower primary children, not for older children.

“It’s disappointing because we feel there are so many good books out there that could be used, but it’s hard to persuade some teachers to take this up,” she said, adding that there was often resistance from parents, who “start worrying when their 11- or 12-year-old brings a picture book home”.

Another benefit of the approach was to break down barriers between the children, as the books focused on migrant characters. “We didn’t anticipate that they would engage so much with the immigrant characters, or show an interest in why they had had to leave their country,” Dr Arizpe said. “They were quite indignant that girls could not go to school in Afghanistan.”

The project, called Journeys from Images to Words, won the 2013 prize for joint work between schools and universities, awarded by the British Curriculum Foundation, the British Educational Research Association and publisher Routledge.

Vivienne Smith, an international expert on picture books, said: “What makes this project important is the way it uses image to help children cross the boundaries of language and culture . Teachers need to know how to use texts like this.”

Author Morris Gleitzman, whose book Boy Overboard was used in the study, visited Glasgow to see the work in action. “I have never been part of anything like this before,” he said. “It seems a very effective way of young people exploring texts.”

Stephen Curran, Glasgow council’s executive member for education and young people, said that more than 100 languages are spoken in schools across the city, adding: “Literacy development that equips our classroom staff to support new arrivals in schools is most welcome.”

www.journeys-fromimagestowords.com Books used in the Glasgow study: The Rabbits by John Marsden and Shaun Tan. A picture book with a little text, about colonisation. At first, the rabbits appear friendly but it soon becomes clear that they are invaders. Gervelie’s Journey: A Refugee Diary by Anthony Robinson and Annemarie Young. A combination of text, watercolours and photographs, telling the true story of Gervelie’s escape from the Congo. Boy Overboard by Morris Gleitzman. Football-loving Jamal and his sister, Bibi, escape the Taliban by travelling to Australia, where more problems arise. Photo credit: CorbisImages to words

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters