The segregation of disadvantaged pupils from their advantaged peers in post-16 education continues to rise, according to new research.

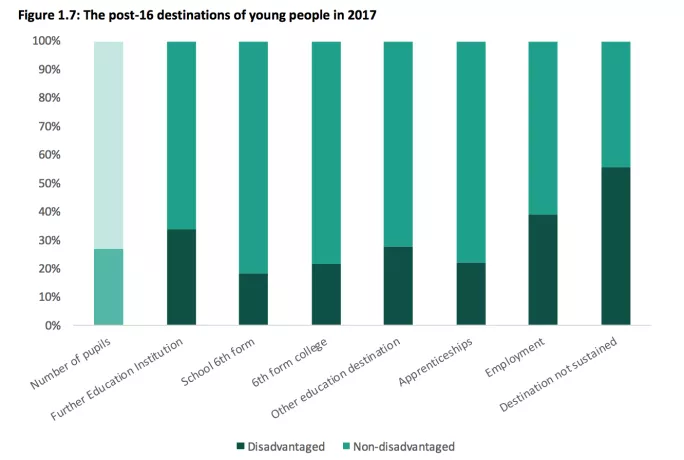

A report from the Education Policy Institute thinktank, published today, says that when it comes to the route pupils take once they leave secondary school, disadvantaged pupils are more likely to choose a further education college, employment or an unknown/unsustained destination compared with advantaged pupils, who are more likely to choose a school or college sixth form or an apprenticeship (see the EPI graph below).

According to the EPI, England’s segregation index is currently 21.8 per cent (based on 2017 data) - which represents a continued increase from 2013, when it stood at 21.0 per cent.

Background: Segregation on the rise in post-16 education

News: Retain choice in post-16 qualifications, say employers

Opinion: Lord Baker: ‘Preserve choice’ by saving BTECs

Social mobility: the segregation index

In a fully equitable system, the segregation index score would be 0, meaning that disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged young people were accessing similar post-16 pathways.

The report says: “Despite their desired role in supporting social mobility, disadvantaged young people have been underrepresented in apprenticeships in recent years.

“And while the proportion of disadvantaged young people taking up apprenticeships has risen in recent years, so has the proportion of non-disadvantaged young people. As such, [apprenticeships’] contribution to segregation has changed little since 2013.”

The report also highlights those local authorities in England with the highest post-16 segregation index. It finds that Richmond Upon Thames had the highest score (38.3 per cent) - and therefore the highest level of segregation between disadvantaged pupils and their peers - followed by Trafford (35.3 per cent), Darlington (35.2 per cent) and Hartlepool (35.2 per cent).

‘Educational inequality’

Tower Hamlets recorded the lowest score (7.6 per cent), followed by Westminster (9.4 per cent) and Hounslow (10.1 per cent).

David Laws, executive chairman of the EPI, said that we are witnessing a major setback for social mobility in England.

“Educational inequality on this scale is bad for both social mobility and economic productivity. This report should be a wake-up call for our new prime minister. We need a renewed policy drive to narrow the disadvantage gap - and this needs to be based on evidence of what makes an impact, rather than on political ideology or guesswork,” he said.

School standards minister Nick Gibb said: “The gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers has narrowed considerably in both primary and secondary schools since 2011. During that time this government has delivered a range of reforms to ensure every child, regardless of their background, gets a high-quality education. We are investing £2.4 billion this year alone through the pupil premium to help the most disadvantaged children.”