- Home

- ‘Teaching is workload-addicted. Teachers seem to believe hard work equates to love for one’s pupils’

‘Teaching is workload-addicted. Teachers seem to believe hard work equates to love for one’s pupils’

On the fourth floor of an unremarkable, grey, pebble-dashed, concrete block of a school building, overlooking the littered streets of Wembley Park, sits our staffroom. Large in size, its open, airy feel makes it arguably the nicest room in the school.

Before we opened in 2014, our headmistress, Katharine Birbalsingh, had to fight with the builders and designers redeveloping the building to ensure that this room did not become the sixth-form common room, but that instead it would be a space for teachers.

As headmistress, Katharine wanted to send children and staff a strong message: at Michaela Community School, staff come first.

Nowadays, some newly built schools don’t even have staffrooms. Presumably this is because it is assumed by some that teachers enjoying a few moments away from the exhaustion of the classroom is a bad thing.

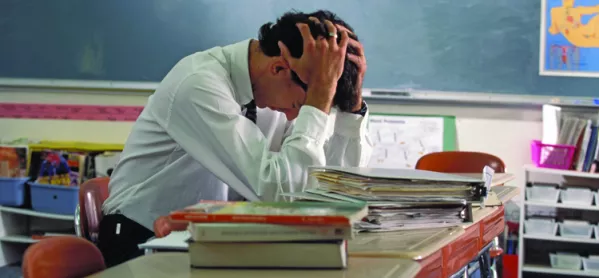

It’s indicative of a wider work-addicted culture in teaching.

Why go to bed early when you could plan another engaging worksheet? Why see your family at the weekend if you could go in to school and run another intervention session? Why have a cup of tea in the staffroom when you could be marking a set of books?

This addiction is driven by the misguided belief that hard work equates to love for one’s pupils. The harder we work, the more we care, the better they achieve. After all, nobody can argue that you don’t care if you work every hour god sends.

No sensible senior leader can say that you didn’t do enough if you worked like a dog all year. Not working hard means your pupils don’t reach their potential, and because most teachers are decent people who genuinely want the best for the kids they teach, they are prepared to put in the time to make the difference. It’s wrapped up in a belief that doing more will garner greater results, and that self-sacrifice is the sole route to pupil progress.

Perhaps sometimes this is the case. Renowned American teachers such as Rafe Esquith, Michael Johnston, Erin Gruwell and Jay Matthews write about the great things they achieved with their classes against the odds.

In the face of gun crime, gang warfare, drugs, street crime, prison, horrendous poverty, and with a lack of funding and structures in place to support them, they help their pupils to overcome these difficulties and go on to transform their lives. It is truly inspiring stuff.

But whilst this may be effective, it cannot - and must not - be the only way to do right by one’s pupils.

Unrealistic and irresponsible

If our system depends on half a million inspiring teachers working all hours, we might as well give up now.

It’s an unrealistic and frankly irresponsible position to take. If we ask teachers to work so hard that they leave the profession or end up suffering from a mental illness, we must introspect and admit where we have gone wrong.

At Michaela, we know that pupils succeed when teachers are happy. And so we put in place many measures that enable teachers to focus on what’s most important, and simultaneously maintain their sanity.

Instead of waiting for the Department for Education or Ofsted to come up with an answer to the question of teacher workload, we recognise that school leaders must take the initiative.

Many of the practices that drive this culture of over-working can easily be dispensed with if senior leaders look at every tiny task through the lens of improving teacher wellbeing.

Galvanised by our streamlined approaches, the Michaela teachers have recently come together to write a book, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Teachers. In it, we describe many of the systems that free up teachers’ time.

At Michaela, teachers on a full timetable can leave at 5pm each day, and don’t have to work on weekends or during the holidays. In over two years, I’ve never seen a teacher struggling with enormous bags of exercise books to mark at home, or panicking about impending observations or report deadlines.

Our focus on continually simplifying and reducing time spent on low impact tasks such as these enables every single teacher in the school to teach every single lesson with purpose, urgency, and the charisma of a Broadway performer.

Precisely because our teachers are so happy and fulfilled, and able to focus all their energies on what matters most, the pupils thrive.

Pupils behave beautifully in lessons, in the corridor, at break time, and as they wait for the bus outside school at the end of the day.

With careful planning, ruthless prioritisation and unrelenting focus on reducing workload, any school can achieve the same outcomes.

Our belief that we are not special and that any school can do what we do, drove us to write our book sharing our approaches. In it, Jo Facer outlines how putting an end to the Sisyphean task of marking exercise books has reduced burden on teachers and increased pupil outcomes.

In his chapter on homework, Joe Kirby describes how simplified, centralised systems and consistency enable all our pupils to complete homework every evening, whilst minimising effort for teachers.

Our approach to discipline - a mixture of a heavy focus on teacher authority, consistent consequences and respect for teachers - means that lessons are stress-free. Rather than struggling to get pupils to sit down, arguing with them or wasting precious learning time amidst classroom chaos, teachers are free to spend every second focusing on teaching their subject.

In Hin Tai Ting’s chapter, he outlines how teacher respect helps to achieve this; in Lucy Newman’s chapter, she explains why teacher authority is both liberating for teachers and vital for pupil progress.

In Jessica Lund’s chapter “No Nonsense, No Burnout”, she explains how we have ruthlessly dropped so many of the practices that are seen as standard in many schools, and how doing so dramatically improves classroom practice and pupil outcomes.

Where in some schools it is deemed necessary to grade observations, to implement a divisive performance management system, to expect all-singing and dancing lessons, to demand four-part lessons and attention grabbing activities, to enter endless amounts of data into boggling spreadsheets that nobody other than the data manager ever uses. Or to spend hours chasing up forgotten homework and to run classroom detentions at lunch times, at Michaela, we do not.

The beauty of Michaela lies in the detail: our ongoing obsession with simplifying systems whilst maximising learning has enabled us to build a school where teachers teach without burning out, and pupils learn without wasting time.

Perhaps if more schools thought about things in this way, we wouldn’t have a teacher workload crisis.

Perhaps, if we moved away from the damaging paradigm of overworking, we’d be able to do an even better job for our pupils, and would have even more fun doing it.

Perhaps, if more schools did things the Michaela way, teachers would be able to achieve the outcomes they are currently killing themselves for with much less effort.

School leaders must take action if we are to solve the problem of teacher burnout.

If there is no emphasis on this at the top of the school, we condemn our teachers to late nights, short holidays, and few weekends. Change the paradigm at the top of your school, and the culture will thrive - and so will the pupils.

To learn more about our methods, and how we reduce teacher workload, order a copy of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Teachers now. Even better, come and visit: you’d be more than welcome.

Katie Ashford is deputy head and director of inclusion at Michaela Community School

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters