- Home

- ‘Violence isn’t a part of history, we face it everyday’

‘Violence isn’t a part of history, we face it everyday’

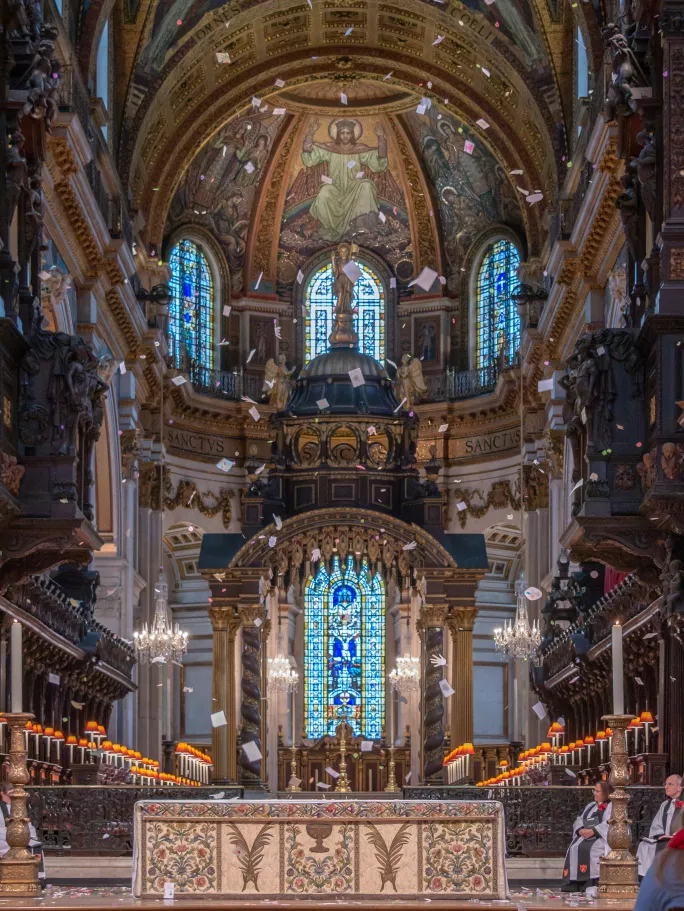

Two thousand pupils and teachers spill into St Paul’s Cathedral in London. As they take their seats, it’s a sea of colour: some have red jumpers, others blue, green, purple, navy with red stripes, some have fluorescent jackets on. They’re from different schools, of different ages, and different ethnicities.

They all have one thing in common. Every single one of them is wearing a poppy.

They’re all here for “100 years on”, a multi-faith event which not only commemorates the lives sacrificed during the First World War, but also asks pupils to pledge to become something that our society so desperately needs: peacemakers.

St Paul’s is just one location where these services are taking place around the UK. Oasis, the organisation behind the initiative, estimates that 100,000 pupils, teachers and communities have come together in synagogues, mosques, community centres and school halls to share poems and prayers, and promise to choose peace, over war.

Brian Nelis, history and citizenship teacher at Oasis Academy Hadley, Enfield, says these events help to open and fuel a conversation about conflict and acceptance, not only 100 years ago but also today.

“At the moment, London is a dangerous place to be, and we are living in an uncertain world,” he says. “Violence isn’t something we just talk about as history, it’s something that is facing us every day. Students have to be involved in a really acceptable way to deal with difference and a really acceptable way to way to deal with conflict in a way that is peaceful.”

Sixteen-year-old Tulula, also from Oasis Academy Hadley, says that the event, and all the work leading up to it, has really opened her eyes.

“I feel like we’re able to take it in more, because we’ve been bought to a different venue, and speaking to different people. Peace needs to be made, we need less violence, less crime, we need to bring peace to the world,” she says. “This event was really peaceful and unique.”

The service is, as she says, unique. The narrative of peace is everywhere: in the songs that we sing, in the speeches and poems that are read, and in the pledges the children make.

The words of Noble Prize winners, Martin Luther King Jr and Malala Yousafzai ring truer than ever. Lines such as “this call for a worldwide fellowship that lifts neighbourly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class and nation is, in reality, a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love for all”, and “why is it that countries which we call strong are so powerful in creating wars but are so weak in bringing peace?” echo around the cathedral.

The children pledge to speak for others who can’t find their voice, to commit to being the best versions of themselves, to respect and embrace cultural and religious differences, and work together to bring about peace in their communities.

Prayers and artwork made in classrooms are dropped from the Whispering Gallery at the very top of the cathedral and sprinkle down like confetti. One of them was handed to me afterwards, it said: “Please God, please may you slowly fade the killing and the hatred from all over the world. May you always protect us from harm's way. Please, can you guide us. Amen.”

It shows them that you have to do something active and not passive, says Nelis.

“A few minutes silence is very useful for people and it’s important that we do that, but I think it’s really important for the pupils to see that they are at the centre of the peacemaking and that they are at the centre of the leadership and to act.

“I often get frustrated when people talk about young people and the future and it’s this phrase that you hear all the time in education, and when you see things like things today, actually I think, well our young students are the present, and it’s important that they are involved in things and that we listen to their point of view,” he says.

And events like this are perfect for opening that door to discussion, says Momtaza Mehri, the young people’s laureate for London.

She wrote and performed a poem for the service in which she spoke of the many stitches of society, and the need to weave them together to make a better future. The pupils, she says, are these stitches, and it’s so important to connect them with the need for change.

“The service was tailored to young people,” she says. “Picking up from people that were closer to their age like Malala, as well as people like Martin Luther King, so it was bringing together the past and the present in a real-life way, and not just having wreaths – which is OK – but it’s different to having petals and prayers that you’ve actually written fall from the ceiling.

She says that many young people can feel like they're talked to, and not with, and that the events of 100 years ago aren’t that relevant to their day to day lives. Events like this help to involve them in the conversations, and help to put things into perspective.

“It’s so much more powerful because they’re in these grand surroundings, but then they have their peers up there and they feel like they have a connection and they’re involved in the general proceedings, I never had that,” she adds.

Steve Chalke, founder and leader of Oasis, says that events like these are a huge part of the solution when it comes to youth violence and crime.

“Everyone asks, what are we going to do about youth crime and youth violence? The answer is schools and education. Hopefully, these kids aren’t going to be in that situation, and they will develop the skills and abilities to negotiate their own emotions and make sure that they are never in that situation. That’s what it’s all about,” he says.

And, the centenary of the end of the First World War is a great springboard to get pupils thinking.

“The First World War was supposed to end all wars, but it didn't. All we got was another war and a century of wars, violence in our cities and verbal abuse from one world leader to another,” says Chalke.

Armistice is an opportunity to get pupils to stop and to listen, not just about the war before or the wars going on now, he says. Otherwise, what’s the point in a two-minute silence?

“In these events are future cabinet members, MPs and leaders. My prayer is that this morning has created hundreds and hundreds of people who will, in their way, make difference,” he says.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles