How can computing be saved in Scottish schools?

Computing is in an “extremely delicate position”.

So says Toni Scullion, co-leader of Scottish Teachers Advancing Computing Science (STACS), the government-funded body dedicated to improving the subject in schools.

Her biggest fear is that computing science ceases to be a core subject in Scotland and that national qualifications - National 5s, Highers, Advanced Highers - wither on the vine.

Yet Scullion, who was a computing science teacher before her current role, is also hugely positive: she maintains that computing’s fortunes can be turned around.

Still, she pulls no punches on why urgent action is needed.

The challenges for computing science

Computing science teacher numbers are falling and student uptake of the subject for national qualifications has nosedived - although there have been some signs of recovery.

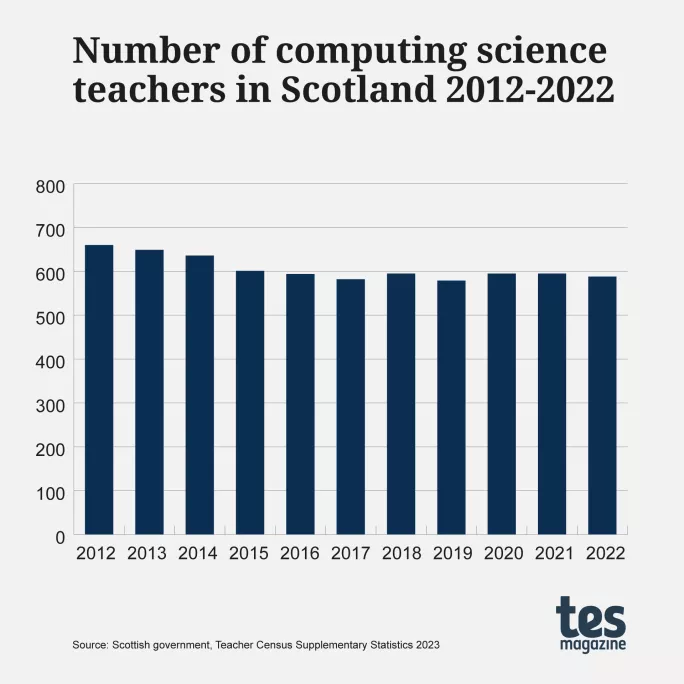

Teacher census figures show computing teacher numbers have been on a downward trajectory since at least 2007 - as far back as publicly available data goes. Back then, there were 788 computing teachers; by 2022 it was 588, down 25 per cent.

And computing teachers aren’t getting any younger.

According to the 2022 teacher census, one-fifth were aged over 55 - a proportion similar to physics (21 per cent) but higher than technical education (17 per cent), chemistry (13 per cent) and biology (10 per cent).

Interest in the subject among students in upper secondary has also fallen sharply. Recently there has been some improvement, but Scullion says if progress does not speed up, it will take decades (she estimates until 2077) before student numbers revert to 2010 levels.

In 2010 there were over 22,000 students taking the subject in the senior phase at Standard Grade, Intermediate, Higher and Advanced Higher level, but last year there were 11,020 taking computing science at National 5, Higher and Advanced Higher. If you include National 4, this rises to 14,340 but it is clearly still well below 2010 levels.

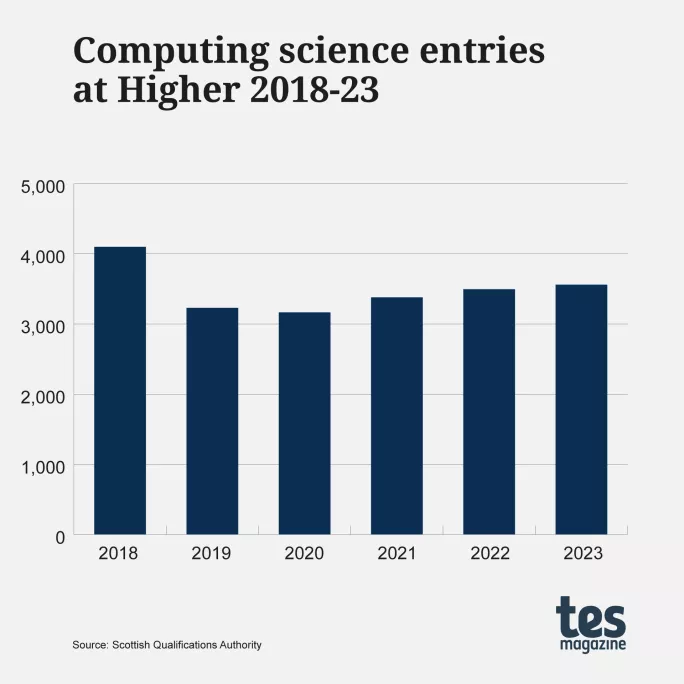

A dramatic drop came in 2019 when Higher computing entries fell by 21 per cent in a year, from 4,099. Higher entries across all subjects fell by just 3 per cent.

This year Higher entries for computing science hit 3,560, which was up on each of the previous four years but still down 13 per cent on 2018.

All this matters, of course, because Scotland wants “a world-class tech ecosystem”, as a recent government review put it.

That Scottish Technology Ecosytem review, published in August 2020, said Scotland’s “fundamental strategic error as a country” was not treating computing science in the same way as maths - which is taught intensively from entry to primary school - or even subjects such as history and geography, which are consistently offered from S1.

It said computing should be “formally taught from first year at secondary school in the same way that we do with science”.

However, the computing science curriculum was “boring” - with many students “put off” computing after studying it at National 5 - and initial teacher education needed to be strengthened and regular training time given to teachers to take account of “the unique pace of change in computing science relative to other subjects”, the review said.

- Related: How a week devoted to computing science boosts Scottish schools

- Quick read: Scottish school offers online courses in shortage subjects

- Interview: Computing teacher and CPD organiser Fraser McKay

- Feature: How a school project evolved into a top edtech company

Since that review, there has been some progress. STACS was created by the government on the back of it, with Scullion and Brendan McCart, also a computing science teacher by trade, seconded from school to lead it for five years.

Computing science teacher Darren Brown, based at Inverness High School in Highland, says “grassroots work” from STACS, as well as Computing Science Scotland (CSS), which provides professional development, has been “a boost” and has led to the “sharing of lots of materials and good practice”.

Fellow computing teacher Fraser McKay, who runs the #cssmeets aspect of CSS - essentially CPD sessions for teachers by teachers - is also enthusiastic about STACS: it has really made a difference because it is “led by teachers”, he says.

McKay is a big advocate of teacher-led CPD that can be easily translated into the classroom, but in the past he found a tendency for computing teachers to be “talked at” by university-based experts.

Both Brown and McKay agree there is much still to do.

Brown says there is a need to invest “real money” to train more secondary teachers and support primary staff to get involved in training.

Some computing teachers, including Brown, would like to see computing benefiting from an approach such as the government’s language-learning policy, known as the “1+2” approach. While the impact of 1+2 has been mixed, a 2022 report into the policy found that languages were “now a priority for schools in a way that they just weren’t before the policy was introduced”.

“Instead of faddy projects and once-a-year tick-box events covering computing science, we need time, staff and training so it is actually delivered in the curriculum,” says Brown.

Variations in provision

The variation in computing offerings across Scottish schools is a major bugbear for teachers of the subject.

Some secondaries see computing science as “a luxury” and “expendable”, says Brown, while others have vibrant computing science departments. Some schools start teaching computing in S1 but students in other schools might get limited experience before embarking on qualifications.

A lack of grounding in computing can create a vicious circle: students take the subject not really understanding what it will involve; they struggle and their subsequent low attainment means schools are put off providing the subject.

McKay wants “parity of importance” with other subjects. At the moment, he says, variation in provision from school to school is not “equitable for learners”.

As one computing science teacher puts it, “The experience of computing needs to be standardised more, in the same way you’ll study Pythagoras regardless of where you do maths.”

Crucially, teachers say, computing lessons in early secondary must be delivered by trained computing teachers and not business studies teachers, as is often the case.

There is also dissatisfaction among teachers around upper-secondary courses.

Computing science is seen by students as difficult compared with other subjects and “too academic”, say teachers.

On X, formerly known as Twitter, one teacher said: “The problem with the N5 in particular is that it is coding, coding and more coding, and those pupils with an interest in [computing science] but not necessarily programming will end up hating the course by Christmas.”

Tracy Mutter, a computing and digital learning teacher at Falkirk High School, says that “it’s all coding” is a reason often given by students for not choosing computing. She suggests “additional optional units that do not involve coding may appeal to a wider cohort of learners, and, in particular, girls”.

Some 19 per cent of Higher entries for computing science in 2023 were for girls; in 2010 it was 24 per cent. In 2010 - before the last major reform of Scottish qualifications - there was also Higher information systems, which had a bigger uptake for female learners (36 per cent) but this was discontinued.

A new lease of life?

Some say that National Progression Awards (NPAs) in subjects such as computer-game development, web design and cybersecurity have given the subject a new lease of life. Others are happy to see these qualifications thrive but not at the expense of traditional qualifications.

Mutter has embraced NPAs but has reservations about them because they do not give direct access to university and they also have a narrower focus than computing science.

Computing teachers also want classification as a practical subject and students numbers capped at 20. They cite issues such as failing hardware, no cash for new software, poor connectivity and “the dreaded DPIA [Data Protection Impact Assessment]”, which can rule out useful resources for what can seem like arbitrary reasons - especially when other schools have access.

However, perhaps the biggest frustration is that many of these concerns have been voiced for years with no tangible improvement.

In 2019 Tes Scotland highlighted that Higher computing entries had dropped by over one-fifth. A lack of computing in primary and early secondary, a dearth of computing teachers and a course seen as “among the toughest” were given as explanations.

Brown says discussions about how to save computing science in schools have been ongoing for 20 years and “the picture is not improving”.

But there is some optimism that the situation is retrievable.

The priority for many is to ensure a sufficient number of computing teachers. That might seem to be a tough nut to crack given that computing graduates are highly employable and can command good salaries. However, the numbers have been crunched in the past and meeting targets for teacher recruitment has been deemed achievable.

In 2019 Professor Judy Robertson, chair in digital learning at the University of Edinburgh, published a paper on the shortage of computing teachers that highlighted how the system needed 50 to 60 new teachers a year - just 1 per cent of roughly 5,000 computing graduates per year.

Scullion describes the number of teachers needed every year in Scotland as “a tiny, tiny number” - last year (2022-23) the target was to recruit 52 computing science student teachers but just 26 places were filled. Given that some computing science students will have jobs lined up long before they graduate, she argues that Scotland needs to get better at promoting teaching as a career.

The University of Glasgow is hoping a new course will “ignite…students’ enthusiasm for a career in education”. In January it is introducing an optional course on computing education for its computing science undergraduates in their final year. So far 30 students have signed up.

Attracting computing graduates

Dr Maria Kallia, the course coordinator and main lecturer, says it aims to position “teaching and education-centric professions as viable and rewarding career paths within computer science departments”.

The possibly of “braided careers” is also being mooted - this would involve working as a fully qualified computing science teacher a couple of days a week and in the tech industry the rest of the time.

A month ago co-founder and ex-CEO of Skyscanner Gareth Williams put out a short survey on LinkedIn “to determine the appetite for this amongst software-skilled employees and their employers” in light of the “severe lack of computer science school teachers”.

Scullion says she is “all for” anything that could boost computing teacher numbers, but does point out that teaching is “a hard job”. Clearly, she has her doubts about how easy it would be to juggle two careers. Other potential issues are the timetabling challenges for schools and pupils’ need for continuity.

Scullion suggests other ways to get more computing teachers into the system, including encouraging teachers of other subjects to become dual qualified and offering Scotland’s standard one-year postgraduate teaching qualification, the PGDE, in more teacher-education institutions (TEIs).

If you want to become a biology teacher you can do the postgraduate teaching qualification in seven TEIs; aspiring physics teachers have the choice of nine different universities. But just three offer computing science - and two (the universities of Glasgow and Strathclyde) are in the same city.

Another simple and “really obvious idea”, says Scullion, would be to offer PGDEs remotely, to reach “amazing individuals who would like to be a [computing] teacher but can’t up and move to Glasgow”.

“My biggest fear is core computing science will just get dropped from the national curriculum and we will just deliver a set of National Progression Awards - like data, cyber, AI - and we won’t have a core set of qualifications. The NPAs are great but they don’t have external exams, they don’t give you access straight to university,” she says.

But the story of computing science’s place in the curriculum could go another way, Scullion adds: “The alternative is that we turn this around and it’s the best movie ever.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article