School suspensions: the scale of the problem revealed

Schools have been saying for some time now that behaviour issues among children have been notably worse since the pandemic.

Now new Department for Education data shows just how bad things have got - the school year 2021-22 saw the highest rate of suspensions ever recorded.

In total 578,280 suspensions were recorded across primary, secondary and special schools, up significantly from 438,265 in 2018-19 - the last pre-pandemic year - and the highest figure since this data has been recorded centrally.

But which school year groups are driving this trend? And which type of pupils?

The rise in school suspensions

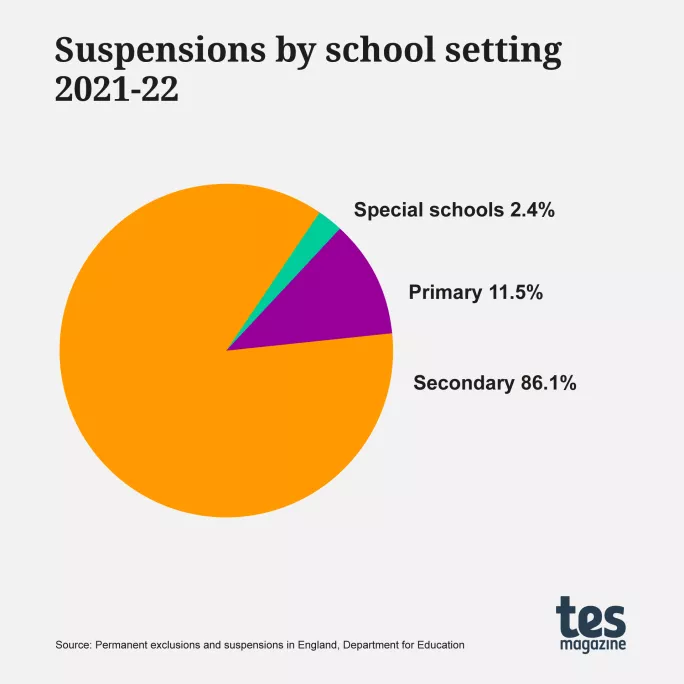

The first thing to note is that the vast majority of the suspensions recorded were at secondary schools.

Of the 578,280 recorded in 2021-22, 498,120 were in secondary, 66,203 were in primary and 13,957 were in special schools.

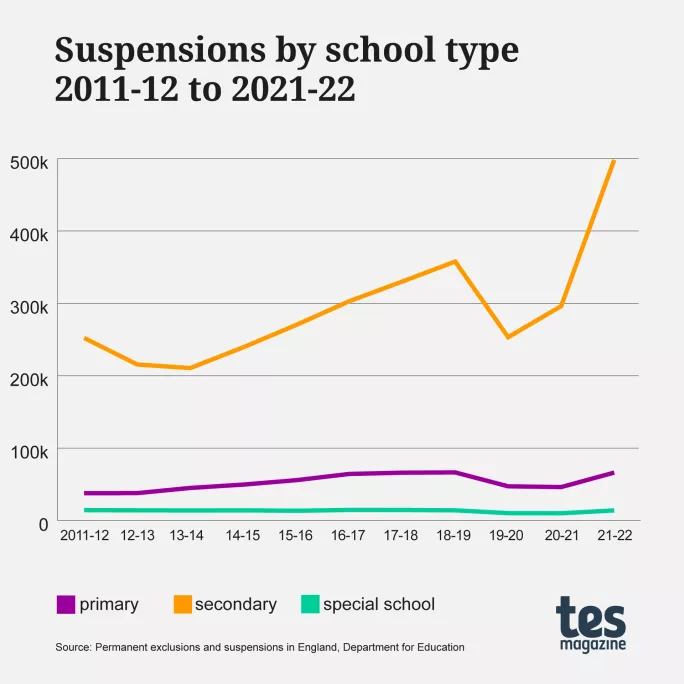

If we look back over the past 10 years’ worth of DfE data for each setting type, we can see that the number of suspensions in both primary and special schools in 2021-22 is fairly similar to pre-pandemic trends, suggesting that life in those settings is generally back to what it was before the pandemic with regards to behaviour issues.

However, if we look just at suspensions in secondary school, we can see a very different picture, with the most recent suspensions number far higher than anything in the previous 10 years - there was a peak of 357,715 in 2018-19.

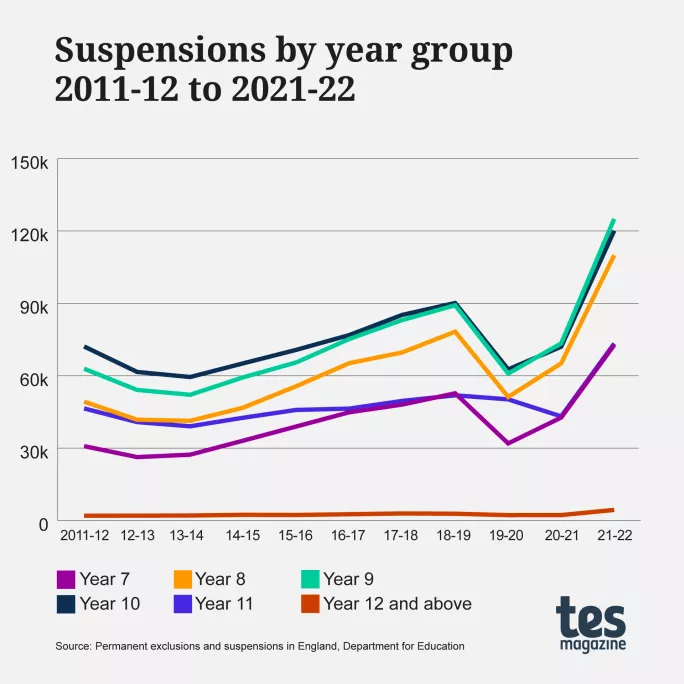

Within this data we can further break the figures down by age group within secondary schools, and the increase in suspensions among certain years groups is stark - chiefly among those in key stage 3.

As the above graph shows, Year 7s in 2021-22 had the highest number of suspensions ever recorded by this age group - an increase of 20,000 to a total above 72,000.

Year 8s recorded 109,960 suspensions, Year 9s went ever higher at 125,000 and Year 10s went to 120,000.

Year 11s were also at their highest, while notably lower than their younger counterparts. However, their total of 73,728 is higher than any pre-pandemic year.

Those in sixth forms in Years 12 and 13 had the lowest figures, as would be expected, although even there a post-pandemic rise was observable.

All of this certainly shows the impact that the pandemic has had on behaviour. This is perhaps most clearly seen in the numbers of Year 9s and 10s receiving suspensions in 2021-22, as they would have spent large chunks of Years 7/8 and Years 8/9 at home due to the pandemic, as safeguarding expert and deputy head Luke Ramsden notes.

“Many schools are indeed finding that Years 7-9 really do struggle with behaviour, and it is really obvious that they are young people who have missed a large part of two really formative years when they learn how to interact with their peers and with teachers in a positive way,” he says.

However, he also warns that another cause of the rise in behaviour problems such as “misogynistic and sexist behaviour and online bullying” is the worrying increase in young people accessing pornography online - a problem highlighted in a recent children’s commissioner’s report.

“This may well have been entrenched by Covid because young people rather moved online and so have got used to being online with quite a low level of parental supervision,” Ramsden says.

Seamus Murphy, CEO at Turner Schools, a multi-academy trust made up of five settings, agrees that students in KS3 are displaying “more challenging behaviour than we have seen previously” and that “there has certainly been an increase in the small number of pupils with significant behaviour challenges”.

Causes of suspension

The biggest recorded reason for suspensions in 2021-22, by far, was “persistent disruptive behaviour”, accounting for 289,617 suspensions.

Second biggest was “verbal abuse or threatening behaviour against an adult’, cited in 112,615 suspensions. “Physical assault against a pupil” accounted for 102,408.

Because the DfE changed how it records this data so schools can now log more than one cause for a suspension, it is hard to accurately compare these figures with pre-pandemic years.

However, the high number of suspensions logged with these causes seems to match up with anecdotal insights from teachers that many pupils are unable to regulate themselves in school and the pandemic has reduced the chance to form the correct social skills for school.

Furthermore, Ramsden says it also shows that pupils are less willing to buy into behaviour policies, in part because parents are now more willing to disagree with schools when a behaviour warning is issued.

“Another legacy of Covid is the extent of involvement that parents have with education, having spent months being able to listen in to lessons,” he explains.

“A lot of school leaders are finding it really difficult with parents feeling that they can and should seek to defend their children from school discipline even if their children have got it wrong.”

Murphy agrees that parents are a big part of the current behaviour picture, explaining that parents often lack support from other services to work with a challenging child. “Unfortunately, some parents who themselves struggle with their children can at times find it hard to work with schools,” he says.

Given this - and the decline of wider support services for parents and schools - schools are being forced into taking action like suspensions more often to try and maintain discipline.

“Stretched schools who find their alternative approaches have failed may have no choice but to suspend pupils. This reflects a failure of the sector, of parents and of support services to handle the most challenging pupils,” says Murphy.

Gender splits and pupils with SEN

This rise in suspensions was also seen across genders - although boys remained far and away the recipients of most suspensions, accounting for 382,412 compared with girls at 195,868 in 2021-22.

However, both groups were also up significantly on anything recorded over the past 10 years, showing that the current issues causing a rise in suspensions are not confined to one gender.

Certainly, the rise in girls being issued suspensions and exclusions has been noted before, with Tes reporting previously on why this may be occurring and how schools have attempted to tackle the issue.

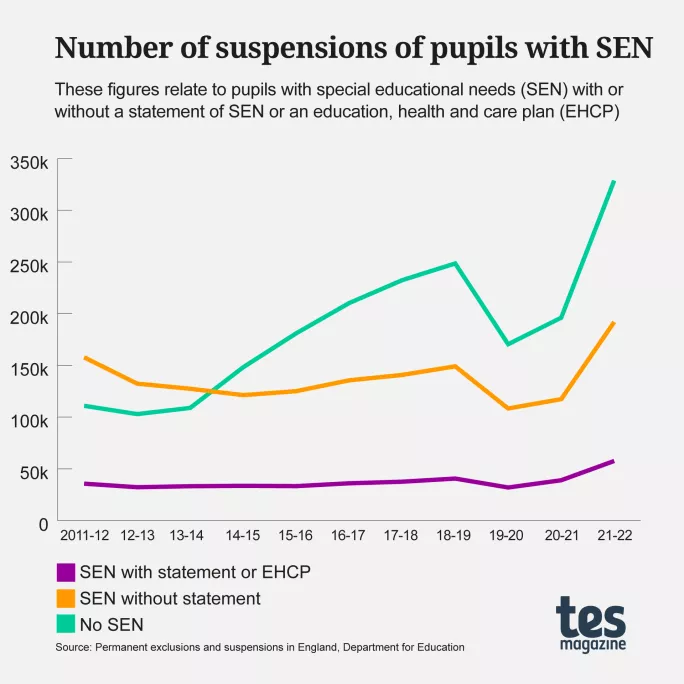

Meanwhile, the data also shows a clear rise in suspensions being issued to pupils recorded as having special educational needs (SEN), including those with a SEN statement and those with an education, health and care plan (EHCP), again underscoring the impact of the pandemic on different groups of pupils.

Keziah Featherstone, executive headteacher of Q3 Academy Tipton, part of The Mercian Trust, says her school has seen issues among pupils with SEN.

”Without a doubt since the pandemic, with all referrals backed up and some children struggling to readjust to school, we have seen certain behaviours escalate. Many students are finding it much harder to self-regulate, at a time when often their families are struggling, too,” she says.

She adds that while schools can look to increase in-house training for those working with pupils with SEN and with EHCPs, the decline of wider support services and ongoing recruitment issues make this a challenge.

“Waiting lists for specialists and Camhs [child and adolescent mental health services] are extremely unhelpful everywhere. With the recruitment and retention of well-qualified experienced staff a challenge, along with funding more tight than I can remember, we are limited to what we can provide in-house,” Featherstone explains.

Schools trying to avoid exclusions

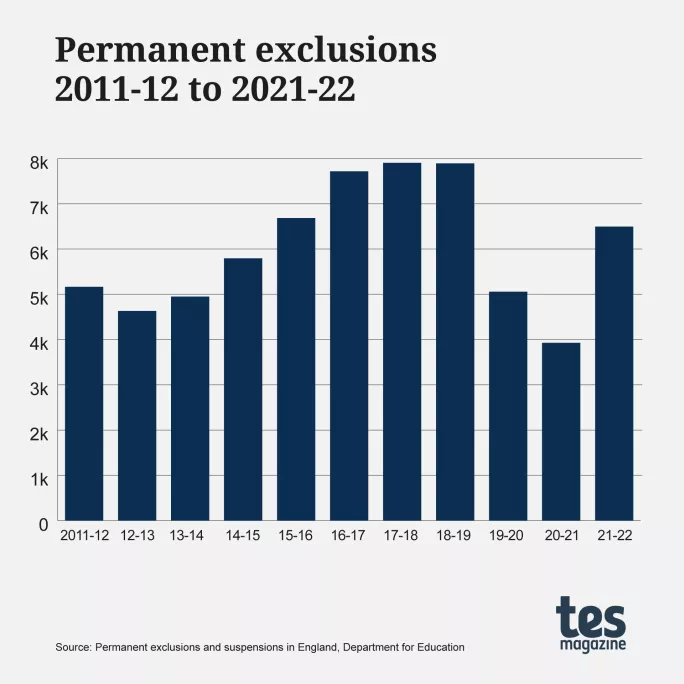

However, one notable finding in the latest data is that despite the huge rise in suspensions, exclusion rates have not risen correspondingly - in fact, they remain below some pre-pandemic years.

For example, in 2021-22 a total of 6,495 pupils were excluded - lower than the four years before the pandemic.

Ramsden says it is clear that schools are trying to “avoid exclusions” wherever they can and hope that a suspension can serve as a stark enough warning to improve behaviour.

Murphy says schools are also likely applying more “nuanced approaches to support children with extreme behaviour problems since the pandemic” rather than simply moving towards exclusions.

Given that this most recent data only covers the previous academic year, sector leaders and policymakers will be very interested to see what the first sets of data for the most recent year (2022-23) show, with everyone hoping that the number of suspensions starts to decline.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article