Is the end nigh for Progress 8 - and if not, should it be?

When you cut through all the noise, Progress 8 (P8) has become the metric by which we officially define our education system in England.

It is what drives the league tables, what sways decisions about the growth of multi-academy trusts (MATs), and how policymakers judge the success - or otherwise - of the policies they enact.

That it is a marker of secondary school impact alone doesn’t seem to matter - P8 still dominates the accountability space.

But should it? And for how long is its reign likely to continue?

Labour, in its Five Missions for Better Britain, has said it will focus on rethinking how P8 works should the party win the next election. And we’re on the cusp of a period when calculating P8 will temporarily be impossible.

So, will this close attention - and suspension of use - find P8 wanting? There are plenty of people who think it has significant issues, and some who believe it to be so easily gamed that it is fatally flawed.

There will be no P8 scores in 2025 and 2026, as no Sats took place in 2020 and 2021 as a result of the pandemic, and so there will be no data to compare secondary outcomes against.

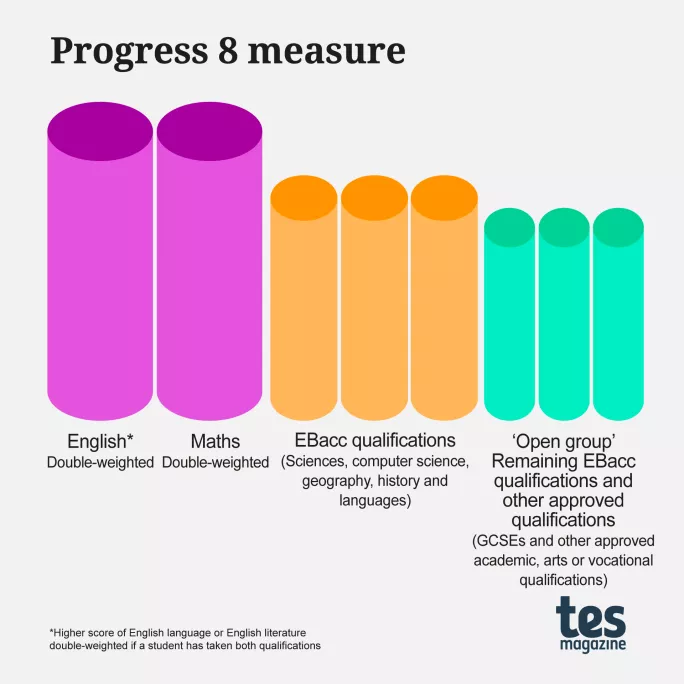

P8 works by comparing a child’s performance in key stage 2 Sats against others nationwide, grouping those children into similar prior attainment groups, and then comparing those pupils’ attainment in GCSEs at KS4 by calculating a national average for the KS4 attainment of each group.

A school’s P8 is worked out by giving each individual child a P8 score where their progression in eight subjects is compared to the national average.

They get either a positive score (made more progress than other children with similar prior attainment) or a negative score (made less progress than other children with similar prior attainment).

The subjects used in this calculation are the same as those used in the Attainment 8 score. All of these individual scores are averaged to create a score for the whole school.

A school with a P8 of 0 means, on average and compared to pupils with similar starting points, pupils at that school made average progress. A minus score means that, on average, pupils made less progress, while a plus score means the pupils made more progress.

Professor Tim Leunig - the man who created the P8 measure for the Department for Education almost 10 years ago - says because of the lack of KS2 Sats data during the pandemic, P8 “absolutely cannot be done” in the years ahead.

Meanwhile, while 2027 could see P8 return, a paper by Professor George Leckie, Dr Lucy Prior, Professor John Jerrim and FFT Education Datalab’s Dave Thomson has also questioned whether using 2022 Sats for 2027 P8 outcomes will be fair.

“Question marks will hang in the air as to [the 2022 KS2 test] accuracy given differential lost learning across schools in 2020-2021, thus potentially impacting upon Progress 8 scores in 2027,” they wrote.

What will happen in those fallow years remains unknown for now. Tes approached the DfE to ask what their plans are for P8 in 2025 and 2026, but they declined to comment.

The fact the issue will only come to a head after any general election in 2024 may mean there is no sense of urgency among ministers to address the issue before then - but it could also mean Labour, or indeed the Conservatives, have a unique opportunity to revamp the system.

For some in the sector, a revamp of P8 is much needed.

Tom Middlehurst, curriculum, assessment and inspection specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders, says the time for change is ripe: “This gap in data allows the government to think differently about how they hold schools to account.”

Plenty of school leaders feel the same, such as Benedick Ashmore-Short, chief executive officer of The Park Academies Trust, who says P8 is the “emperor’s new clothes” and has run its course.

“We all know it’s insane, but no one says it,” he says. “You can’t predict a grade in drama using KS2 Sats data. It causes a rift with primary and secondary and we’re conflating two systems at a key point where they diverge.”

Jonny Uttley, CEO of The Education Alliance, agrees: “P8 has largely been debunked. It is still gameable and it hugely benefits schools with particular cohorts and, by definition, disadvantages others.”

The issue of how cohort characteristics would impact P8 is one of the main contentions with the measure and was raised in 2016 by Professor Rebecca Allen, now director of the Centre for Education Improvement Science at UCL Institute of Education, but who was then with FFT Education Datalab.

She conducted research that argued P8 would unfairly impact some schools - secondary moderns - and benefit others - grammar schools - due to their pupil intakes.

Discussing this with Tes in 2016, Allen explained if schools received a lower P8 score because their intake had fewer pupils from affluent and supportive home environments then it “would seem unfair to schools serving disadvantaged communities”.

She stands by this view today, and a look at data outcomes for P8 since then seems to back it up. For example, the average P8 score of disadvantaged pupils was -0.57 in 2023, and for non-disadvantaged pupils, it was 0.17.

Another point of interest when it comes to cohorts is the difference between those pupils with English as an additional language (EAL) and non-EAL pupils. EAL pupils averaged a P8 score of 0.51 in 2023 and non-EAL pupils -0.12.

For girls, meanwhile, the average P8 in 2023 was 0.12, and for boys it was -0.17.

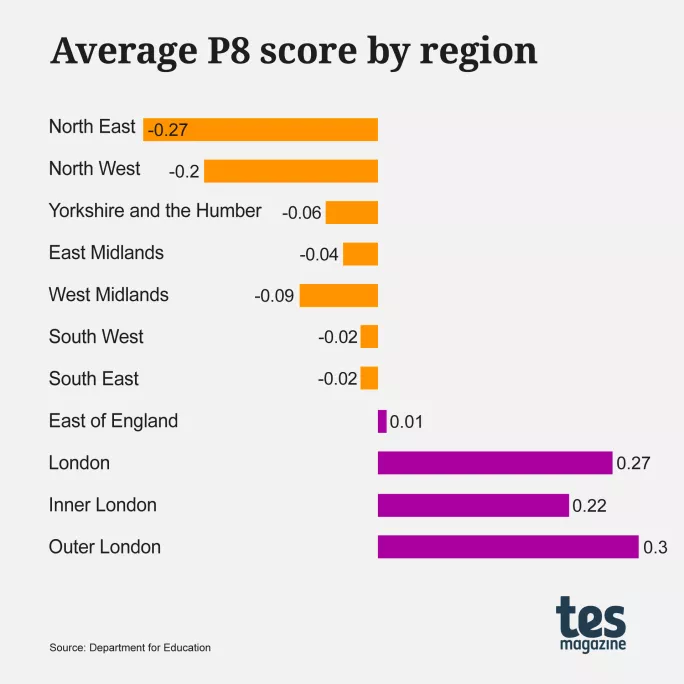

Lastly, the difference in the performance of pupil groups also reveals a stark North-South P8 divide. For instance, the North East has the lowest average P8 score in the country at -0.27 for 2023, whereas Outer London has the highest at 0.30.

Some have argued that this is partly down to school quality, but this isn’t something P8 can tell us, says Thomson.

“Schools’ results differ, even when we adjust for context, but we don’t know if that is due to the school, or due to other factors, such as levels of support at home,” he says.

Chris Zarraga, director of Schools North East, agrees. He says: “While P8 does factor in prior attainment, it fails to consider other contextual challenges such as long-term disadvantage.

“Although the impact of disadvantage is not unique to North East schools, our region has the highest rates of long-term disadvantage, and the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis have only exacerbated this perennial issue for our schools.”

This scepticism of the suitability of P8 to judge the difference in progress made in schools in the North versus the South particularly is shared by the director of the Durham University Evidence Centre for Education, Professor Stephen Gorard.

“The North-South divide exists in terms of the raw scores - but once you take context into account, our research shows there is no difference in progress,” explains Gorard.

Zarraga worries that because “current measures often fail to reflect contextual factors”, P8 results mislead the public as “economic and geographical factors are mistakenly presented as educational ones”.

Yet ignoring contextual factors was entirely the purpose of P8 when it was first introduced back in 2016, as it replaced the old system of contextual value added (CVA) - which aimed to quantify how well a school did with its pupil population compared to pupils with similar characteristics nationally.

This meant that schools with more pupils on free school meals (FSM) had lower expectations than schools with fewer FSM pupils, as this group has historically achieved lower GCSE grades than their non-FSM counterparts.

However, CVA was seen as being open to gaming by both primary and secondary schools, as a government White Paper issued in November 2010 outlined.

It says: “Existing measures of performance encourage ‘gaming’ behaviour - with primary schools over-rehearsing tests and secondary schools changing the curriculum to embrace ‘equivalent’ qualifications which count heavily in performance tables.”

What’s more, the White Paper also said it is “morally wrong” to have an “attainment measure which entrenches low aspirations for children because of their background”, such as expecting FSM pupils to make less progress than non-FSM pupils.

This paper paved the way for the creation of P8.

Professor Leuing maintains his view that P8 works because it does not lower expectations for disadvantaged children, but instead forces the system to find solutions to create equitable outcomes for that group.

“It would be dangerous to say we expect less from less resourced children. Instead, we need to look at the reasons why and look for answers. I’d hate to see that question crushed by moving to a system with contextual factors accounted for,” he says.

On this point, Middlehurst agrees. He says exams “should provide a mirror to the national performance of students” and agrees with Professor Leunig that “CVA can mask these gaps”.

However, he says even with this acknowledgement, the way P8 is calculated still means many schools are held accountable against cohort intakes over which they have no control.

“Many question whether it is fair or reasonable that the additional challenges faced by their communities are ignored in the way they’re held accountable for their outcomes,” says Middlehurst.

Here we come to the crucial point of the argument both for and against P8: to what extent can the school be made accountable for the difference of attainment in non-disadvantaged and disadvantaged pupils? Does a large disparity between the two tell us there is a problem in our schooling system? Or a problem in society?

For its part, Ofsted says data like P8 is never used solely for its judgements.

“While we take pupils’ results into account when evaluating the impact of the curriculum, inspectors are trained to base the quality of education judgement on a much wider range of evidence - no school is judged on the data alone,” an Ofsted spokesperson told Tes.

But the fear of how a P8 score is being held against schools has undoubtedly led to some unintended and highly damaging consequences - chiefly off-rolling, ie, removal of certain pupils to ensure their attainment outcomes do not influence a school’s P8.

For schools where P8 is given the highest priority, it’s a risky situation to have a cohort made up of a significant proportion of children who fall into the category of “less likely to make more progress than the average”.

In these situations, because of the way a school’s P8 is calculated, even in a school where the majority of pupils make more progress than expected, this can be wiped out if a few significantly underperform, an issue raised in 2017 by Jon Andrews from the Education Policy Institute.

The government acknowledged this in a 2018 report discussing P8, writing: “It can drive perverse incentives in the system in the absence of a counterbalance incentivising schools not to exclude pupils...this can be particularly true for schools with challenging intakes.”

Measures have since been put in place to limit the impact of “outliers” on a school’s P8 score (see details in Annex B here) and there has been much publicity aimed at stamping off-rolling out. But Uttley believes it is still happening (you can read his thread about this on social media platform X here).

Dr Elizabeth J Done, lecturer in inclusion at the Institute of Education at the University of Plymouth, says that her research also makes it clear the problem remains.

“It’s hard to quantify how much off-rolling is happening because of the nature of the problem - it’s unrecorded and so often goes unreported,” she says. “But the amount of anecdotal evidence is overwhelming and, in my work, I have seen P8 has had a role in fuelling and incentivising these practices.”

In addition, even if not technically classed as off-rolling, some schools have been seen to push students to enrol at an alternative education provider, such as University Technical Colleges (UTC), as Simon Connell, CEO of Baker Dearing Educational Trust, the charity that supports UTCs, notes.

“We still have schools off-rolling, there are fewer, but it still happens,” he says. “Previously about a third of our intake would be made up of pupils who had been wrongly encouraged by their schools to apply to the UTC because they wanted them off their roll.”

When this argument is put to Professor Leunig, he makes the point that it is the high-stakes accountability that drives the behaviour - not the measurement.

“Off-rolling will always happen when you have high-stakes accountability,” he says. “P8 is better than the old five A*-C at GCSE metric because that didn’t recognise the progress made at the lower end. P8 certainly doesn’t make it worse.”

Professor Leunig gives the example of a school with a Year 11 cohort of 180 students. Here, he says that “if a school off-rolled two students, the boost to the P8 wouldn’t be as great as it would be to the five A*-C metric”.

It’s clear to see that schools with lower numbers of FSM pupils have higher P8 scores. Looking at the schools with the highest P8 scores, only one in the top 100 has more than 50 per cent of FSM pupils.

There are other issues with P8, too. Done makes two claims against P8 that many agree are problematic: cohort selection to boost P8 and narrowing of the curriculum to boost it.

On the first point, Done says overly complex “admissions process” and “expectations in the school behaviour policy” are designed to put off families whose children are less likely to make progress between KS2 and KS4. This point was also recently made by The Sutton Trust in a paper that concluded poorer pupils were less likely to gain the top school places.

And on curriculum narrowing? The claim of those who introduced P8 was that it would help deliver a broad and balanced curriculum, but many argue it has actually reduced subject choice.

This is because, critics argue, as P8 measures eight subjects - and five of these are already decided (English, maths and three English Baccalaureate (Ebacc) subjects - a choice out of sciences, computer science, geography, history and languages) there are only three choices left for other subjects.

Tom Richmond, founder of education think tank EDSK, says this means it has created a “dominance of EBacc subjects” so there is “little space” for the creative subjects.

“There is essentially no room left for music, art, design and technology, drama and other such pursuits, even if pupils prefer these subjects to more academic options,” he says.

This is a criticism that has dogged P8 since its rollout. It was also noted in the DfE research report Understanding schools’ responses to the Progress 8 accountability measure published in 2017.

The authors wrote that “balancing the ‘demands of Progress 8 with the ethos and focus of the school’ was felt to be creating a narrower curriculum - for schools with both negative and positive P8 scores”.

This narrowing of the curriculum happens as schools wish to focus their students’ efforts on those crucial eight buckets, and are therefore reluctant to offer qualifications that won’t count, or allow students to take more GCSEs in a range of subjects through fear that splitting their attention will result in lower grades.

However, Professor Leunig is not concerned. He says: “Pupils not studying the arts isn’t necessarily a problem.

“Arts subjects can be explored outside the classroom more easily than, say, physics. I would say it is more important that students take more conventional subjects as these are core for a successful future in Britain and have strong links with future earnings.”

Meanwhile, Thomson says that although entries in the arts have fallen, it cannot all be blamed on the introduction of P8.

He says: “There has been a small decrease in the proportion of young people entered for one or more qualifications in creative subjects since P8 was introduced in 2016, however, we do not see a consistent decline in the entry rate.”

So, what could replace P8 - either for the two years coming up without results or in the long term?

As noted, the DfE said it had no comment on the situation, although Tes understands work is being done to consider what other metrics could be used instead of P8 for 2025 and 2026.

Professor Leunig would like to see “nothing at all” in its place for the two-year gap coming up.

“I’d hate to go back to five A*-C, but on the other hand, we know accountability matters. I wouldn’t like to have nothing permanently, but what is put in shouldn’t be random,” he says.

In the long term, he sees no need to meddle with what is there.

“I don’t think the P8 measure needs to change,” says Professor Leunig. “Under the Labour plan [to create a compulsory vocational or arts bucket] grammar schools will struggle - but if that’s the price we pay to keep P8 then that’s a compromise.”

However, others are more vocal about what should be done. Olly Newton, executive director of The Edge Foundation, says it has convened two groups formed of MAT leaders, headteachers, unions, academics and statisticians, to flesh out how P8 could evolve - or be replaced.

The first of these groups is solely focused on P8 and is “putting together options for new ministers (of any party) who want to make tweaks to P8 to improve areas like curriculum breadth and school freedom”.

He says one idea proposed is to consider whether it might be better to reduce it to Progress 5 to create a smaller core and more options for flexibility.

Meanwhile, the second group, dubbed Rethinking Accountability - running in partnership with Rethinking Assessment - is “looking at the bigger question of what the performance tables could look like if they were to become something more like a ‘balanced scorecard’”.

This idea of tweaking P8 - or rather accountability more generally - to be a broader metric of school performance is popular with many.

“I’d like to see it kept, it’s a reasonable measure,” says Thomson. “I don’t think a measure that isolates the effect of a school on pupil achievement is possible given the data we have.”

However, Thomson makes the point that P8 is given a “privileged space” and would prefer a suite of measures that were used instead.

Sir Jon Coles, chief executive of United Learning, the largest MAT in the country, agrees. He says P8 is a good “summary measure” because “it gives equal weighting to the performance of all pupils, rather than over-emphasising marginal gains on the borderline”.

He adds that it considers performance across a broad curriculum, including core and foundation subjects, measures the progress children have made from their starting points and, unlike CVA, it measures progress for all children at the same starting point.

However, he would like to see a broader range of measures used to assess school performance.

“What the government should do (alongside publishing its preferred measures) is make it easy for parents to look at whatever measures they are interested in,” he argues.

“For example, a parent might be interested in how well a school does in music and art; or in how well children with special educational needs or disabilities do at a school; or how many children get GCSEs at grade 7+, including all three sciences.

“This data exists and it would be easy to make it accessible to parents in a way which allows them to find out what they want to know. [But the government] is now deliberately making it harder for parents to do this or to compare schools. This is directionally wrong.”

Whoever is in power after the next election, there won’t be much time to make a call on P8. With 2025 and 2026 forcing a rethink at least temporarily, the measurement of school impact will be in tight focus.

What emerges from that period remains to be seen, but a simple reinstatement of P8 in its current form would seem - on the evidence of all the above - very unlikely.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article