Why economics demand has left teachers in short supply

I read a recent Tes article - The curious case of the missing psychology teachers - with interest, not least because I was guided through my first year of teaching by a kindly psychology head of department.

More pertinently, though, was that many of the issues the subject faces are the same as the subject I teach: economics.

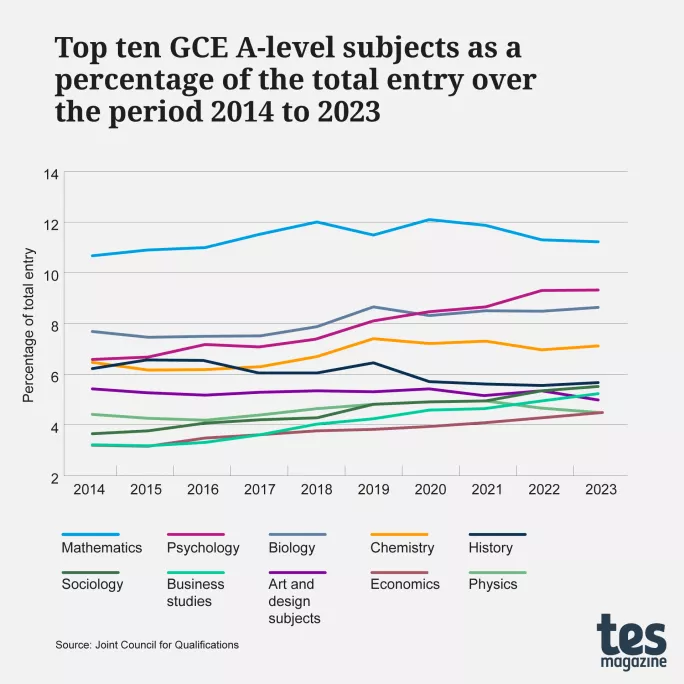

In recent years, economics has broken into the top 10 A-level subjects, nudging geography into eleventh place as students are increasingly keen to study a subject seen as important in the modern world.

Yet, just like psychology, the subject suffers from low recruitment of new teachers with the subject lumped into the “other” category, which, as the recent piece pointed out, is a long way from hitting its target.

A confusing path

My own route into teaching underscores this is not a new issue.

I became an economics teacher by accident. I’d decided to career change into teaching in my 30s after a chance conversation with a lost Year 7 on a bus.

I’d originally planned to teach history and quickly realised two things: there was a gap in the market for economics teachers and the financial crisis of 2008 had reignited interest in the subject, including mine.

However, it transpired that training to teach economics was not straightforward. Firstly, there are hardly any postgraduate certificates in education. You can train on the job, but only if the school offers economics or business in key stages 4 and 5. Many don’t.

You can train to teach economics in a sixth-form college, but that doesn’t work if you’re already in a school.

The most common solution is to train in a different subject and accidentally-on-purpose convince the school to let you have economics as the second subject.

Teaching two subjects at once

What I did was apply for a job teaching economics as an “unqualified” teacher on the promise that the school would help me find a suitable initial teacher training (ITT) programme.

This turned out to be very challenging as the school could only meet the requirements by having me teach RS in KS4.

Economics has a lot of tough, technical theory that you need to master before you can hope to teach it effectively. I had a first-class economics degree, but the school courses have their own content and emphasis, never mind the fast-changing nature of the subject itself.

You definitely don’t need the distraction of trying to learn to teach a completely different subject.

As the only economics teacher, I was lonely and lacked the kind of informal, “chat in the corridor” support that trainees should have. It was hard not to have anyone to discuss decisions with, such as which resources to use, which exam questions to set, how to apply marking criteria or how to extend more able students and support struggling ones.

Help is out there, though. I went to as many other schools as I could and networked, quickly building up contacts of teachers I could ask for help when stuck on tricky topics. I attended subject cluster groups and found suitable training courses.

A department of one

I found colleagues very generous. One even put on a suit during his half term and came to observe me at my school. I pay this forward now, helping other teachers who are also an economics department of one.

Sometimes they have had the entire department dumped on them at short notice, and they may not even have an A level in the subject.

All this before the lesser-known hazard of the job, which is that random colleagues will stop you in the corridor, or by the photocopier or on your way to the loos, to ask you quietly whether they should remortgage, what Jeremy Hunt was on about or what a “final salary pension” might be.

Why does the Department for Education not organise training in these popular sixth-form subjects? Added together, economics, psychology and sociology (another subject in the “other” ITT bracket) account for around 150,000 A-level entries each year and numbers are only growing: that’s almost 20 per cent of A-level entries.

Teacher training

Clearly, we need to do something. Perhaps schools that do offer economics should be more vocal about being able to offer placements to universities or school-centred ITT to ensure the opportunity to put training into practice.

Schools could even start training these teachers themselves. I recently came across a school about to start training five economics with business teachers, having given up on advertising for them.

However, they can only do this as they have a huge department. Supervising a trainee in a situation where there’s only one economics teacher is obviously not going to work well.

Lastly, we all need to keep lobbying the DfE to plan better to match the supply of teachers to the demand (sorry, couldn’t resist). Otherwise, we will continue to have what we economics teachers like to call “widespread market failure” and students will miss out.

Josie Aston is an economics teacher at a comprehensive in London

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article