Key stage 4 school performance tables were published for the first time in three years yesterday.

While we know from a range of evidence that the pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged pupils, it is less clear what impact this has had on different schools, and how government catch-up support may have mitigated these impacts.

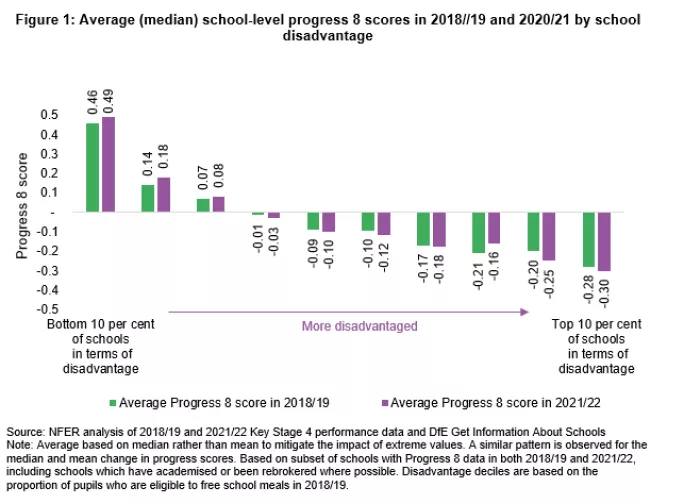

So, what does the new data tell us? It suggests that the gaps in average progress scores between different types of schools have widened over the past three years.

Against the backdrop of the current political turmoil, it is an important reminder that long-term, well-targeted and adequately funded support is necessary to adequately address these gaps.

Progress 8 scores and disadvantage

Progress 8 was introduced as the principal headline performance measure for all secondary schools in 2015-16. It is a measure that aims to capture the progress that pupils in a school make from the end of primary school to the end of key stage 4.

Progress 8 scores are constructed by comparing the GCSE outcomes of pupils with those who achieved similar scores in key stage 2 across the country. A Progress 8 score of zero indicates the performance of pupils in a school is in line with pupils who had similar KS2 results.

A positive Progress 8 score indicates that pupils in a school have better attainment compared to pupils with similar results, and vice versa for a negative score.

Before the pandemic, more disadvantaged schools (as defined by schools with a higher percentage of pupils eligible for free school meals) had - on average - lower Progress 8 scores than more advantaged schools.

This is partly due to the fact that pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds achieve about half a grade lower in each subject compared to pupils with similar prior attainment. Research has highlighted that non-school factors, such as family engagement and material deprivation, which are largely outside the control of schools, play a key role in explaining these differences.

We know that the pandemic has not affected all pupils equally. More disadvantaged pupils were less likely to be able to engage in remote learning and were more likely to have their schooling disrupted in 2020-21.

As such, our expectation is that disadvantaged schools will have seen the biggest declines in progress. But is this hypothesis borne out by the data?

Less progress than pre-pandemic

Unfortunately, it seems to be.

Our analysis shows that there is a negative relationship between the level of disadvantage of a school and how their progress scores changed between 2018-19 and 2021-22.

In general, more disadvantaged schools were most likely to see a decline in their progress scores. In other words, there has been a widening in outcomes across schools with different intakes, despite the additional catch-up support which has been in place.

It is nevertheless important to recognise that the magnitude of the changes are not large in the context of the pre-existing gaps, as the below image shows.

Figure 1: Average (median) school-level progress 8 scores in 2018-19 and 2020-21 by school disadvantage

Implications for the system

These findings serve as a reminder that while there might be a published performance table, school-level results need to be treated with caution.

This year’s performance data will not only capture the differences in intakes across schools but also the stark differences in circumstances that schools and their pupils have faced during the pandemic. The new data is only provisional at this stage.

The latest GCSE data also highlights that the level of provision and targeting of catch-up support for schools has not been sufficient to prevent a slight widening in outcomes. This is only likely to be exacerbated by the current cost-of-living crisis.

It is crucial, therefore, that more targeted and longer-term support is provided to disadvantaged pupils to help close these gaps, and that funding is appropriately targeted across schools such that schools’ ability to access government catch-up support is not constrained by the wider financial pressures that they are currently facing.

This is not only to prevent widening inequalities but also to support our longer-term economic prosperity.

Jenna Julius is a senior economist at NFER