- Home

- The good and the fad: how crazes conquer schools

The good and the fad: how crazes conquer schools

At first, Jamie Barry didn’t fully register that a steady proliferation of girls in his school were walking around wearing colourful bows in their hair. Then, one day, things came to a head - quite literally.

“The bows started getting bigger and bigger and the girls were competing to wear the biggest and most colourful bow,” says the headteacher of Parson Street Primary School in Bristol. “I thought, ‘Hang on, this is getting a bit ridiculous now.’”

It’s a reaction that many a headteacher has had to many a school fad. For as long as there have been schools, there have been trends that seem to come from nowhere and dominate the attention of pupils. They stick around for a few weeks - maybe months - and then quickly fade away again with as little fanfare as they arrived.

Unlike some schools, Parson Street Primary didn’t ban the wearing of JoJo bows, the aforementioned brightly coloured and oversized head ornamentation with which his students had become obsessed. “We just told the kids to keep it modest and they have been pretty responsive to that,” says Barry.

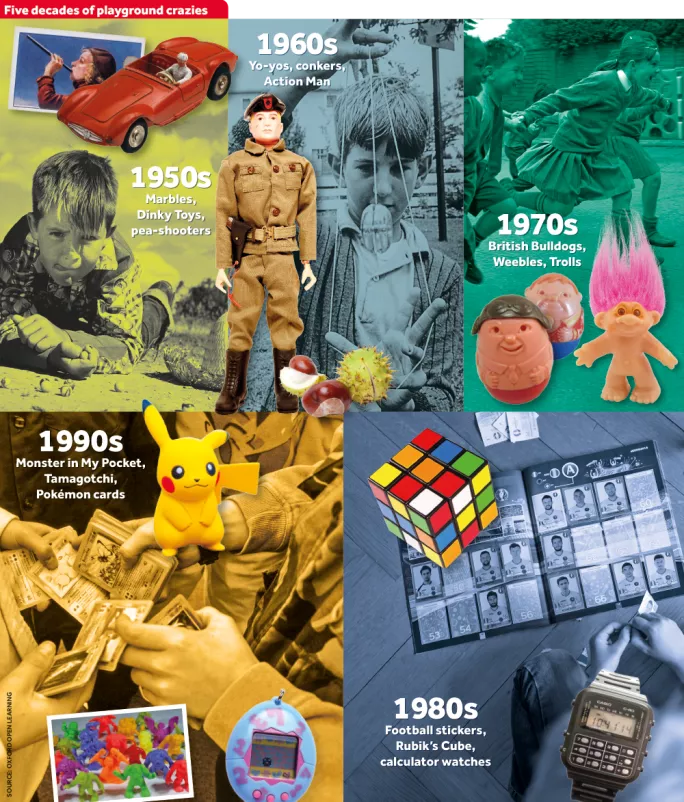

But many schools did ban them, just as they banned fidget spinners this year, or Tamogotchis in the 1990s, or football stickers in the 1980s or yoyos in the 1960s. Faced with distracting fads, schools have traditionally opted to eradicate them from the school premises in response.

Is that the right option? Before you answer, you first need to understand why school fads happen and what drives them. For in the madness of a fad, there is some method that should interest teachers and perhaps be instructive as to how they might stop - or perhaps accommodate - the temporary obsessions of the school-age population.

To understand the mechanics of a fad, you first have to understand mimetic theory, which was espoused by the French-born philosopher and anthropologist René Girard.

“Girard said the reason we like things is because other people like things,” explains Nir Eyal, behavioral designer and author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products.

“If you take a product like a fidget spinner, there is no good reason why people should like them other than the fact that they see other people liking them, and that gives them value. So once a few kids start bringing fidget spinners into class, other kids want to know what these things are.

“Even though they’re just a piece of cheap plastic, the fact that some kids are getting really into them and won’t let other kids play with them increases the value of the product through mimetic desire.”

Objects of mimetic desire

Schools are ideal breeding grounds for fads because they typically take off when a small pool of people who are very visible start playing with something. The effect is then magnified.

“In a closed, strange, unnatural environment like a school setting, where you have a small group of people who you see frequently, healthy trends and unhealthy trends can spread very quickly,” says Eyal.

How do small pockets of use of a certain item become a fad? In the pre-internet age, this might have happened initially through students from different schools mixing with each other, before hitting a critical point where magazines and television propelled the item to the dizzy heights of fad status. Nowadays, the process can happen a lot quicker thanks to social media.

For every trend that makes it to fad-status, there are many more that don’t. There are countless things that remain regional or even local to schools and never take off nationally.

Predicting which will become a full-blown fad is almost impossible, says Eyal - not just for teachers, but for any manufacturer that wants their toy or other product to run amok in schools.

“It’s very difficult to predict these sorts of things with any forethought,” he explains.

“With hindsight, you can always think of reasons why these things take off when they do. But it really is about a critical mass and when something enters the zeitgeist, so to speak, it reaches a certain tipping point. This only increases the power of mimetic desire.”

Some crazes are culturally limited, adds clinical psychologist Dr Ben Michaelis, but “crazes like fidget spinners that involve non-verbal activities - Pokémon GO and Rubik’s Cube are other examples - are easily transmitted cross-culturally, depending on how they are introduced.”

While spotting a fad is difficult, predicting its end is a lot easier.

“It is always the same reason that fads die - they become predictable,” says Eyal.

“Once something is no longer in short supply and everyone can get their hands on it, suddenly it becomes less desirable.

“Take the example of fidget spinners: they are flooding the market right now. You can get them very cheap everywhere and very soon everyone who wants one is going to have one.

“They’re not going to be special anymore because they’re not going to be coveted or desired, and therefore other people won’t desire them. So a great way to kill a trend is to flood the market.”

Considering the fact that students are pretty much programmed to follow a fad and that those fads are almost always fleeting, should schools really spend so much energy trying to tackle them?

Pick up the phone

Most schools would answer yes. Whether the students are helpless victims of a natural desire or not - and however fleeting that desire may be - the insistence is that if something distracts from learning, it must go.

“Our phone policy is ‘see it, hear it, take it’ - the phone is confiscated, there’s a sanction and the phone can then be collected at the end of the day,” explains Stephanie Keenan, curriculum leader of English and literacy at Ruislip High School in West London.

“The same applies for other toys or possessions that distract the student or others from their work.

“[But] even if the school didn’t ban them, I would in my classroom. It’s fine to have fidget spinners, loom bands or football cards during break or after school - that’s their downtime - but never in lessons. If parents object, I would just explain it was distracting from their learning and they are in class to learn. They can play at break or at home.”

Matt Pinkett, a secondary head of English in the south-east, takes a similar stance.

“The thing with fidget spinners is, I’m yet to see a single kid’s focus increase as a result of having one,” says Pinkett.

“In my opinion, they’re a distracting force and, in the discourse around these, while much of the focus has been on the kids, there’s another issue: they distract me.

“I put time and effort into planning lessons. It is soul-destroying to see kids comparing fidget spinners when, really, all I’d really like them to do is fidget a pen across a page.”

Yet some argue that a blanket negative response to fads is unwise - some, for example, may bring benefits schools can utilise. That’s perhaps most true for those fads that, like fidget spinners, involve simple repetitive tasks, says Michaelis.

“There is some research evidence that fidgeting helps people to think more clearly - especially for people who have problems paying attention,” he explains.

“There is also research demonstrating that any form of repetitive behavior has positive effects because it provides a release of sorts, and may be connected to positive feelings associated with the parietal lobe.”

Whether those positive effects contribute to learning - rather than take away from it - remains to be seen. But Nathan Atkinson, head at Richmond Hill Primary School in Leeds, thinks that certain fads potentially offer positive opportunities for learning.

“I’ve worked with members of staff who have started their own football sticker collection because it gives them a way of building a relationship with children who previously wouldn’t have engaged in learning,” says Atkinson.

“There was a certain group of boys in the school who were hard to reach in terms of their learning, but through football stickers we had them writing, doing maths and behaving themselves because we linked rewards to the stickers. So, for instance, if they achieved their goals for the day we would give them ten minutes’ swap time at the end of the day. That kind of thing can be used really positively.”

But such benefits are outweighed by the massive potential for negative impacts of a fad or fads, counters Barry.

“We want the children to have happy playtimes and lunchtimes, but equally I can’t control the swapsies they do or the rarity of the objects they bring into school, and it’s for that reason sometimes we will ban them,” he explains.

“I think it’s good for children to have interests and hobbies, but it’s more the consequence of having those fads than the fad itself that leads to trouble.”

It’s obviously also important for the children to learn a bit of self-regulation. Forcing them to try and control their fad urges could help here.

Yet in banning the fad, could you in fact be fuelling it? Scarcity, as the mimetic theory suggests, is a key driver of the fad phenomenon. By trying to make schools free of any fads, you suddenly make those fad items highly prized in that context.

Losing their cool

A better option, argues Stephen Petty, head of humanities at Lord Williams’s School in Thame, Oxfordshire and a Tes columnist, is to kill the cool of fads by turning them into a learning resource.

“Teachers have - intentionally or unintentionally - become very adept at doing this and must surely take credit for the rapid decline in many a craze,” says Petty.

“A coordinated response by different departments is particularly effective in this respect. Soon after the fidget spinner, say, has become the subject of a calculation question in maths, used for a poem in English or put at the heart of a design lesson in technology or a globalisation activity in geography, it rapidly loses its cool and swanky status. The gloss is stripped away and the thing is exposed for what it is.”

It’s a coping strategy that Michaelis describes as “absolutely brilliant”.

“As soon as something new and cool has been adopted by people who are - at least according to the students - the antithesis of cool, it loses the sense of specialness and will quickly fade,” he says.

Fade they may, but the memory will long live on in those who experienced a fad. Every teacher will fondly recall at least one trend. But if they do damage learning, they obviously need to go. And perhaps the best way of getting rid of them is not to ban them, but embrace them. Banning fuels the fad; teachers getting in on it might just stop it in its tracks for good.

Simon Creasey is a freelance writer

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters