- Home

- John Hattie takes on his Visible Learning critics

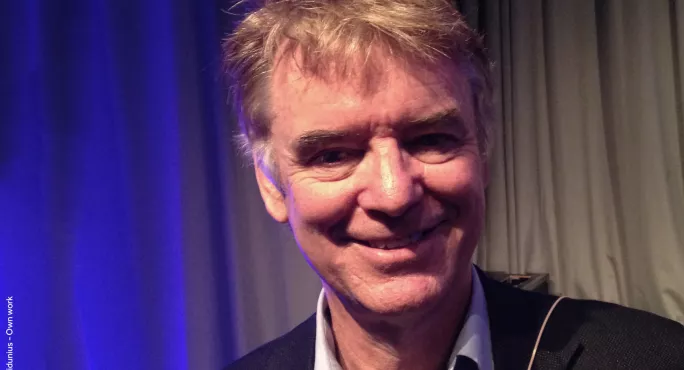

John Hattie takes on his Visible Learning critics

The way John Hattie tells it, his fame is an accident and the fact that you know his name at all is largely down to his wife.

“When I wrote the book, I wrote five versions,” he reveals. “The fourth version was the one I was most proud of - it was 500 pages, full of data and tables, and my wife said, ‘Which two people in the world are going to read this?’ So I threw it away, and rewrote it.”

The book he ended up with was, of course, Visible Learning, published in 2008 and dubbed by a Tes reporter on its release as the “Holy Grail” of teaching.

Visible Learning

The book synthesises huge swathes of education research data to present an analysis of what works in education. It is now one of the most read and cited books in teaching - but also one of the most controversial, too (more of which later).

Speaking on this week’s Tes Podagogy podcast (which you can listen to below), Hattie, now professor of education and director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, explains that he never expected the book to be popular.

“I never dreamed it would sell over 1 million copies,” he says. “And the fact it lasted even a year, let alone 10 years, I can’t explain it.

“I am delighted that people have found it interesting and people have taken up the ideas and critiqued it, but certainly when you sit down and write a book as an academic, it is a lonely activity, so if someone comes to the party it is wonderful.”

The trouble with party guests, of course, is that they can believe the party to be something it is not. And things can get awkward. And they certainly got awkward for Hattie.

John Hattie under fire

Hattie believes his work has been widely misinterpreted. For example, he has been criticised for ranking the different interventions in his book, seemingly suggesting that one approach is better than another in a hierarchical way.

That was never his intention, he says - the ranking was actually an after-thought. When his wife read that final version five, she still thought it lacked flow.

“So she invented the barometers that run through it so it would flow better, and at the last minute I stuck the ranking at the end,” says Hattie. “In many ways, it kind of worked, it got attention, but it also caused a lot of hassle where people have misunderstood my work. They say they have to do the stuff at the top and the things at the bottom don’t matter: clearly they had never opened a page in the book. The book is all about the overlap.

“It was this notion of these things as a tack-on [that was wrong]. My fundamental argument - and the reason we wrote the book - is that it should be about how teachers think, how school leaders think, as they do their job.

“That is a message I probably did not get as well across in the first book, but I have made up for it by publishing another 25 on the same areas, to try and get that message across that this should be about how you think about what you do, the evidence you use, the critique you use - that list gives you probability statements, but what really matters is how you implement it.”

Growth mindset problems

He clearly finds this “misinterpretation” upsetting. He compares it with the experience of his “good friend” professor Carol Dweck and her growth mindset theory - she, too, feels her work has been misinterpreted (as she told the Tes Podagogy podcast).

“Certainly Dweck’s work, like mine, has been dramatically misinterpreted by many people,” he says. “She is doing a lot of work to try and correct that, and I am the same….Like Carol, I have learned that implementation is the hardest part of this game.”

The ranking is not the only criticism of his work. Another frequently cited issue is his use of the Common Language Effect Size - supposedly a way of more easily communicating the effect size of a given intervention. Some years after the book was published, a Norwegian professor and her class emailed Hattie to say he had got his figures wrong.

Hattie admits the error, but feels it has been blown out of proportion.

“What is kind of amusing is that it took almost four years for some students in Norway to discover the problem,” he says. “They emailed me when I was on a plane, and I told them I would come back to them. When I got back home, I looked at it and emailed them back and said, ‘Yes, you are right.’ I contacted the publishers, we changed the next editions.

“But it took nearly four years for someone to discover that, so clearly [that measure] did not work [anyway] - no one had understood it or used it.”

Corrected errors

The fact that it keeps being brought up, despite him changing the text, rankles.

“Some authors keep publishing and saying that because I made that error, you have to ignore everything else - but it was just another way of getting the point across. It turns out I didn’t need it, I wish I had never used it, so, of course, I regret that error,” he says.

The data he uses in his meta-analysis is a third big critique of his work. Some have claimed his trawl of research caught bad data in the net, that this data contained bias - a bias that was then transferred into his eventual findings. Professor Robert Slavin goes into this in great detail in a blog for John Hopkins University.

Again, Hattie feels hard done by. In his recently released Gold Papers, in which he deals with the various critiques of his work, he writes:

“The argument is that the quality of the research included in the Visible Learning dataset is more akin to junk food than organic produce grown with love. If the ingredients are junk, so the criticism goes, then so must be the results….

“…If we only included the perfect studies or meta-analyses, there would be insufficient data from which to draw conclusions. Indeed, in the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC), which only allows RCTs [randomised controlled trials] and similarly high-quality designs, the median number of studies in each of the 500 reviews is two! It is hard to draw conclusions based on two studies.

“So, we have a choice to make. We either limit ourselves to collecting the perfect studies or we mine the lot but take great care over how we interpret the data and the conclusions that we draw from them. In the case of Visible Learning, the latter approach was taken.”

He does go on to say that he is going back over the studies to make reliability a more explicit part of the analysis. (WWC have been contacted for comment).

Evidence-informed teaching

What is Hattie’s view of the Education Endowment Foundation and the What Works Clearinghouse that curate evidence for teachers?

He thinks they have a role, but he believes we have begun to look at “evidence” in the wrong way.

“The days of evidence are kind of over, the days of interpreting the evidence are what matters now, and that is what I am most interested in,” he says. “We are very good at curating evidence and making evidence, but let’s switch and talk about dissemination and utilisation. That is what I wanted to do with Visible Learning: take this voluminous research we have and put it out in a way we can use it to actually make a difference.”

In making things accessible, of course, you risk oversimplification or misinterpretation. Hattie is clear that this is an area academics have to get better at, and equally clear that many of his academic critics resent his efforts to do this work.

Better communication

“We in academia have to get better at the art of translation,” he says. “We as academics have not understood that every teacher has a strong theory about how they teach. Until we stop and understand that, we are not going to have an influence.

“What I try and do in my work is understand what it means to be a teacher reading this work, how will they understand it. I get teachers to read my work and tell me what they understood and did not - if they did not understand it, that is my fault.

“So we need to get smarter at talking to teachers. Most of us in academia are paid by the taxpayer and we have an obligation to find ways to speak back to our communities in ways that are not patronising, that are informative and that are useful. Like Carol Dweck, like me, you get a lot of flak for it. Success can be measured by the number of arrows in your back, but you have to take that.”

Multiple viewpoints

It’s a robust critique of his colleagues, but Hattie is robust about many things. When you throw him a topic, he comes back with an opinion devoid of the usual professional pleasantries: he has something to say and is happy to give you it unfiltered.

For example, on teachers saying they don’t need research, they know what works for them?

“If a teacher says, ‘It works for me, and here is the evidence,’ then I am listening,” he states, “but just having an opinion you like something deprofessionalises our area.”

On teachers becoming researchers?

“I am not a fan of teachers as researchers. I would rather they be evaluators. Under evaluation you are asking about value, merit and worth: is this the best resource to use to make a difference to these kids where they are right now? Research often asks the ‘why’ question; why is it so? Evaluation is about so what?

“I have nothing against teachers doing research, obviously, but I think they would be better off being evaluators.”

On research leads being simple conduits for research into schools?

“I would be a little worried if you were putting people in schools to simply dredge through literature.”

Cognitive load theory

What about everyone’s favourite theory at the moment, cognitive load theory?

“CLT is one of our best theories,” he says. “It has been around for many, many years and is now in high interest. But when you look at the curriculum in the UK and Australia - oh my goodness, the expectations of what you have to get through in a class!

“There is a sobering exercise you can do where you ask a teacher to sit with a student throughout the day and witness the incredible demands on what kids are asked to do. When you look at the load on them, a lot of it is peripheral stuff. A lot of what we ask kids to do is lots of doing, and it requires a lot of cognitive load for that doing, but it is not how we should be spending our resources and energy.

“Certainly in my own work, we are looking at the most effective strategies to use and it turns out the best strategies depend on where you are in the learning cycle…. The research on cognitive load says loudly and clearly to me, that we need to be better at understanding what are the skills, what is the requirement of students in this particular lesson at that moment and how do we ensure we focus on those and not on the peripheral stuff. That could be extremely powerful.”

Making a difference

Hattie has plenty more views where these come from: that we “overplay” the importance of curriculum; he advises education ministers not to visit Finland or Singapore; that there is no evidence that accountability improves outcomes; that teaching is not actually as complex as people make it; that we don’t fully understand group work.

It’s refreshing to hear someone of Hattie’s stature speak his mind this freely. Then that’s what he is all about: trying to make the complex simple; trying to make the academic accessible; and trying to make what happens in people’s minds visible.

He admits that he is not always successful in these aims, but say that if he can change the conversation in teaching by trying, he will be content.

“When I look back now, changing the notion of what works to what works best, if I could have any influence or credit for doing that, I would be very happy,” he says.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters