- Home

- Pisa’s ‘rich’ resource risked by ‘useless’ rankings

Pisa’s ‘rich’ resource risked by ‘useless’ rankings

Education ministers have called on the Pisa study to communicate its findings better – so that the focus is not on “useless” headline rankings.

Concerns were voiced today that the “rich array of information” provided by Pisa (the Programme for International Student Assessment) is being lost because it is instead being treated as a ratings agency for school systems.

With the study run by the OECD due to publish its Pisa 2018 findings later this year, participating countries are starting to focus on what the results could mean for them.

Portugal’s secretary of state for education, Joao Costa, said: “The data provided by Pisa is very, very rich, it is extremely rich. But the risk is that we only look at Pisa’s ranking of countries and this is the most useless part of Pisa.

Global domination: How Pisa came to rule the world

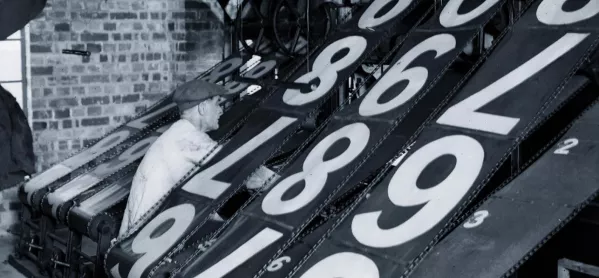

Last Pisa results: Education rankings in science, maths and reading

Warning: England held back by rote-learning, warns Pisa boss

“Everyone is very happy that Portugal is coming up but we are halfway. So let’s not be convinced that everything is done. Let’s read the whole thing.”

Andreas Schleicher - the OECD official who runs Pisa - was also speaking at the Global Education and Skills Forum (GESF) in Dubai, and accepted the point that a narrow focus on the rankings was unhelpful.

But Mr Costa said the problem was partly caused due to the way that the OECD presented the Pisa results.

“I think Pisa is not yet communicating well,” he said. “Because, for instance, collaboration is a key competence for the 21st century, problem solving is a key competence for the 21st century.

“But then we have the [last] Pisa launch and we are all talking about language, mathematics and science. And some months later we get results for collaborative problem solving and no one is really paying attention anymore politically speaking.”

In England education ministers have been happy to focus on headline Pisa rankings when it suits them. Michael Gove made the country’s apparent relative Pisa decline a key justification for the last major bout of school reform, when he was education secretary.

Mr Costa’s concerns today were backed by Leonor Magtolis Briones, education secretary for The Philippines, which participated in Pisa for the first time last year.

“Pisa has to communicate, and we who are participating in Pisa also have to be prepared to communicate, particularly the analysis of the results,” she said speaking at the GESF. “Because the public can have its own analysis.

“That has to be taken into consideration especially in very sensitive political environments. People take Pisa very, very seriously.”

Mr Costa is also worried about the impact that Pisa – which focuses on literacy, maths and science – can have on other subjects.

“The other risk [of the headline Pisa rankings] is the risk of narrowing down the curriculum,” he said. “Because if we go two points down in mathematics or language there will be a huge fuss about more teaching hours for language or mathematics.

“And we may be targeting the wrong side, because we need arts in the curriculum, we need humanities in the curriculum because they are also tools to develop the skills that are then assessed – even in the literacy and the mathematics [Pisa] domains.”

He added: “In many countries Pisa is taken as the rating agency for education systems – the Standard & Poor's of education – and this is the worst because then all of a sudden we disregard all this very rich array of information that we get in Pisa and we are only concerned about the absolute result.”

Mr Schleicher said he had “sympathy” with Mr Costa’s concerns about the risk of rankings and praised Portugal as a good example of how to avoid it.

“What I admire most in Portugal is they could have said ‘ok we are the fastest improver in mathematics, we have figured how to teach mathematics, let's become better on this’," he said.

“In fact what they concluded is ‘we know how to do these things so let's focus our energy on the big things that are missing in our system’ – the 21st century skills – even at the risk of losing out a little bit on mathematics. That is a really far-sighted use of Pisa.

“This is the ideal example of learning from it - not to be driven by the narrow rankings. Pisa is very complex and offers a lot of different dimensions and it is important not to boil this down to a single metric. The world is multi-faceted and we need to engage with it.”

But he conceded: “It is very hard to convey that to the public and the rankings can dominate the discussion. I can see the risks but the opportunities [from Pisa] are enormous.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters