- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

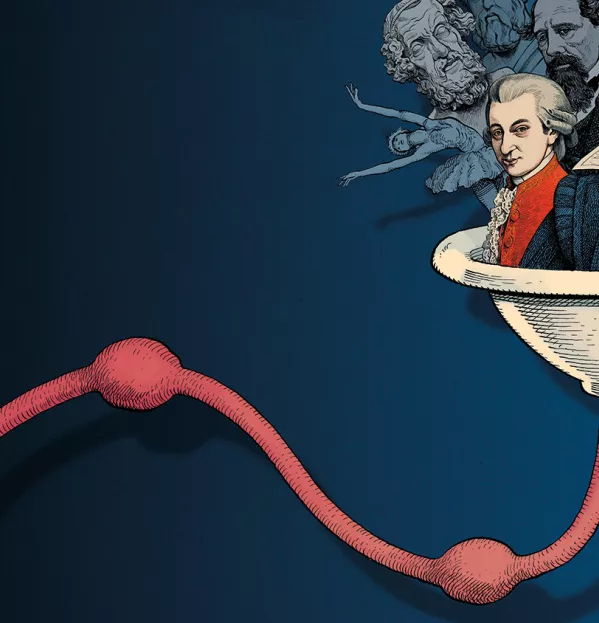

- Why poorer pupils need more than cultural capital

Why poorer pupils need more than cultural capital

The only C-word anyone can think about in education right now is Covid-19. An estimated 2 million children in the UK - the majority of whom attend state schools - have spent relatively little time in the classroom since the start of January because of it. But, for me, the C-word that will impact the education of our pupils the most in the long term is still “capital”.

Coined by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in the 1970s, “capital” takes three forms: economic, social and cultural. The last of these has frequently been cited by Ofsted as a key element of its latest drive to enable England’s “most disadvantaged” learners to “succeed in life”. Its unarticulated assumption, therefore, is that economic and social capital play a lesser part - or can be less pivotal - in this life success.

But this contradicts the concept’s founder. The intrinsic link between the three types of capital was always made clear by Bourdieu. He recognised that, in order to access the cultural capital needed to achieve educational success, one had to come from a wealthy family with beneficial social connections.

It’s evident that key elements of cultural capital are entwined with privilege, says Diane Reay, a University of Cambridge sociologist and champion of disadvantaged pupils. She laments Ofsted’s “reductionist” approach to learning. Important elements of cultural capital are inextricably linked with privilege - they’re not qualities you can “separate off and teach to the poor and working class”, she has told the Guardian.

This notion - that the three forms of capital can’t be separated - raises important questions. How equitable can an education system really be if it judges children on the wealth and success of their parents? Regardless of their background, parents usually want the best for their children. However, because of the aforementioned three forms of capital, they are not equally placed to get it.

Research has consistently concluded that parents with more money, a better education and - as a consequence - more social confidence are actually the biggest contributors when it comes to a child’s chance of success. So, while Ofsted chief inspector Amanda Spielman, in an article in New Statesman, argues that “extracurricular development, trips and speakers” are what it takes to “broaden children’s experiences and exposure to life”, I’d argue that Britain’s children are already far too exposed to life in a country perpetuating a political plague of historic proportions. The remedy for the 4 million children living in poverty? Surprisingly, it isn’t a visit to the British Museum.

I don’t dispute the importance of cultural capital. As a drama specialist, I’m often the first person to advocate for what the arts can offer our children. But, within our current context, we can no longer pretend that the biggest deficit that a disadvantaged child faces is not enough time spent reading Shakespeare.

Food poverty, caused by a lack of economic capital, is accelerating rapidly, with more than 2 million children experiencing food insecurity since the pandemic began.

The government’s pitiful free school meal parcels were branded “disgraceful” by the prime minister, and nutritionists stepped out in force to condemn the poor value for money and lack of nutritional content. For the 14 per cent of children who, according to a University College London report from 2016, regularly skip breakfast as a result of poverty, this may be their only meal each day.

Research into malnutrition among young people living in poverty is not promising. Study after study highlights how malnutrition directly affects performance, limiting pupils’ working memory and affecting brain functions responsible for mood and motivation.

Our government accepts that poor economic capital plays a part in our children’s futures. Last summer, exams regulator Ofqual designed an algorithm that resulted in about 40 per cent of teacher-assessed grades being downgraded, with children from disadvantaged backgrounds being the most affected. Meanwhile, private schools saw the proportion of students achieving the top A-level grades increase by twice as much as their comprehensive counterparts.

Educational disadvantage

Days later, after a humiliating climbdown was forced upon the government by teachers and students, education secretary Gavin Williamson promised that his focus was on “making sure youngsters get the grades that they deserve”.

Despite this statement, though, private school pupils are still - nearly 12 months into the pandemic - carrying out more remote learning than those at state schools, according to Sutton Trust research. Despite living in poverty, many disadvantaged pupils were left without laptops for several months while schools were closed. And research suggests that many low-income households don’t even have a desk or table for a child to study at.

Add to this the fact that parents with more economic capital are, statistically, more technologically adept and better able to educate their children about online safety, and we can see how Williamson’s wish isn’t being fulfilled. On top of the disparity in economic capital sits a variation in social capital. Comprising parental expectation, obligation and relationships that exist within the family, school and community as a result of parental influence, social capital boasts benefits for children in terms of health, happiness and educational success. This social capital offers another form of advantage to those who possess it.

Research by sociologists Sandra Dika and Kusum Singh indicates that, where children have both parents at home, fewer siblings and higher parental expectations, they are more likely to exhibit positive behaviour in school and to be more committed to their learning. They also show higher levels of self-efficacy when it comes to classroom conduct, owing to their possession of social capital.

Of course, not all of us hail from families with 2.2 children. For those who live in crowded conditions, with parents who are unable to support them, statistics are bleak. Schools can supply scores of worksheets and staff to support study, but the extent to which a parent or carer provides a climate for learning and the extent to which, in turn, a child internalises this climate is a deciding factor in educational success.

But parental influence is not everything. Pupils who feel part of a school community gain, too. A 2007 study showed that these pupils were likely to have “higher levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy and self-concept of ability, and lower levels of stress than other pupils”. So those disadvantaged children who have good school friendships and positive relationships with teachers could also do well - if they had actually been in school during much of the pandemic. Those parents furloughed from jobs in retail or hospitality don’t make the cut as key workers, even though their children often need constant community contact to a greater degree than those living with more affluent adults.

Unsurprisingly, where there is a difference in parental behaviour, finance tends to be the limiting factor. For a substantial number of children, parental income impacts on several aspects of their education, including the school they attend, their access to extracurricular and cultural activities, and the support they receive with homeschooling - the last being particularly important in our current climate. Here, we can see the impact of economic and social capital, as more affluent parents feel more confident offering advice, supporting their children with work and guiding them on visits - albeit virtually - to cultural locations.

The impact of child poverty

So, it’s clear that all three forms of capital are inextricably linked, with economic capital acting as the root from which all other types of capital grow. It is, perhaps, in light of this conclusion that we can understand the most alarming statistic of all: the impact that the coronavirus has had on the attainment gap between rich and poor pupils. It has grown by 46 per cent in a single year, according to a study by the National Foundation for Educational Research.

If ever there was a time to note that the impact of capital in education goes far beyond reading the right books, seeing the right plays and visiting the right museums, it is now. If genuine progress is to be made in this area, we need to take a long hard look at our society.

Schools face an uphill battle in rectifying social problems and entrenched inequalities that existed before their pupils were even born. While a Google arts and culture tour around the Musée d’Orsay might be enjoyable, and may even inspire some pupils, it isn’t contributing to their community contact or lining their parents’ pockets. Cultural poverty is not the pressing priority.

But it’s important to recognise that education can and does provide genuine opportunity. As teachers, we must always strive to offer pupils the best chance at a start in life and mitigate inequalities where possible. While a level playing field might seem far out of reach, the way in which the pandemic has highlighted the poverty endemic in our society offers a promise of potential progress. From cafés offering free meals to children to community-organised laptop-donation projects, Covid has caused communities to come together to ensure that no child is left behind.

And there are ways in which schools can address the capital disadvantage, too, from establishing homework and breakfast clubs, and offering extra tutoring to encourage independent study, to outreach projects to help engage working-class parents in their children’s education.

Providing pupils with cultural capital is laudable as an aim but it will only really make a difference once we have begun to tackle economic disadvantage and ensured that our children have what they need to succeed.

Danielle Jones is a drama and English teacher at a secondary school on The Wirral

This article originally appeared in the 26 February 2021 issue under the headline “Capital punishment”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article